Dark Forces Conspire to Destroy the Radiant One: The Assassination of Akhenaten—Part II

Akhenaten’s religious experiment, which was launched in the imperial capital Thebes and later nurtured in the new city Akhetaten, resulted in dramatic changes. Not only did the king oust the panoply of traditional gods – with Amun becoming the prime object of hatred – but he also instilled a deep sense of fear and confusion in the hearts of the populace and priesthood. The pharaoh’s actions were deemed dangerous, fanatical and detrimental to the nation’s interests. Were these the reasons that ultimately propelled his enemies to bring about his end?

Marked by a grotesque, at times startling, artistic convention; androgynous depictions of Akhenaten in colossal statuary were the result of his religious philosophy that sought to assimilate and embody both male and female characteristics. In short: The Pharaoh wished to be seen as the Creator of Life. From Karnak. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Of Gold and God’s Wives

During the New Kingdom, Egypt’s temples grew fabulously wealthy, thanks to a significant portion of the war booty and taxes, among other sources of revenue that were donated to the treasury of the state god Amun. Regular tributes of precious metals, livestock and slaves from subjugated realms made the temples powerful; and the high priest at Karnak rivaled the king’s prestige. By the time of Amenhotep III, Amun-Ra’s priests had become a state within a state and were perhaps within range of imperiling the supremacy and sanctity of the crown. Nebmaatre’s exceeding attention to the Aten was his way of countering their influence.

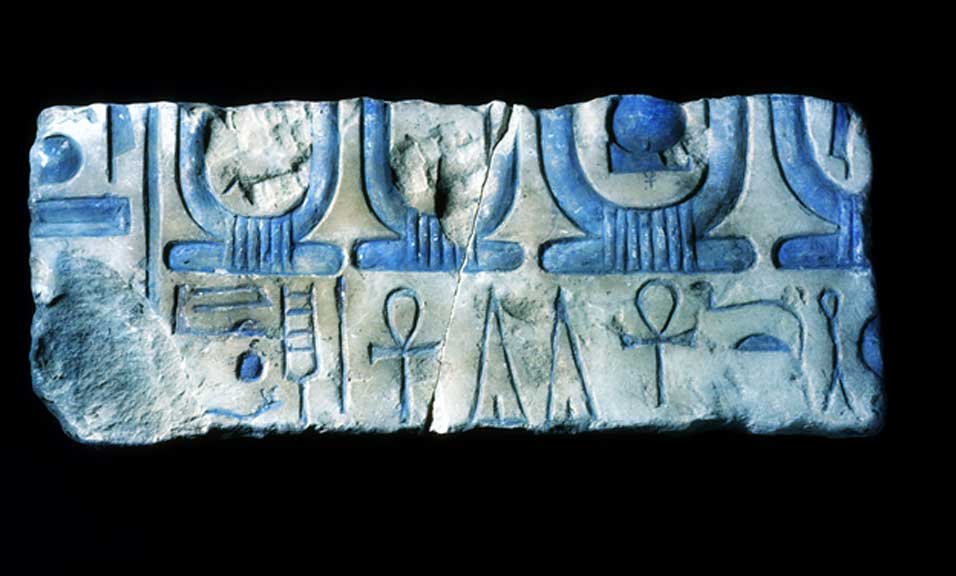

Painted limestone relief with cartouches of the Aten. Probably originally from Amarna (Akhetaten), but discovered at Hermopolis (Ashmunein). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

But pharaohs, particularly in the Eighteenth Dynasty, seem to have always had trouble dealing with the overweening ambitions of the clergy. Egyptological researcher, Kevin Robinson, notes: “Several extant papyri dating to the reign of Ramesses VI list the taxable income and general holding of land throughout Egypt. The amount in temple hands rivalled the pharaohs’ holdings; and it has been estimated that by the reign of Ramesses XI they controlled more than a third of productive land.”

The sun briefly set on Karnak Temple and the Amun clergy when Akhenaten assumed the reins of power. Those were dark days when the iconoclast spared no effort to erase the memory of the state god—only for his policies to ultimately backfire on him.