From Piso to the Baby Drusilla: The Legal Aspects of Damnation Memoriae - the Punishment of Non-Existence

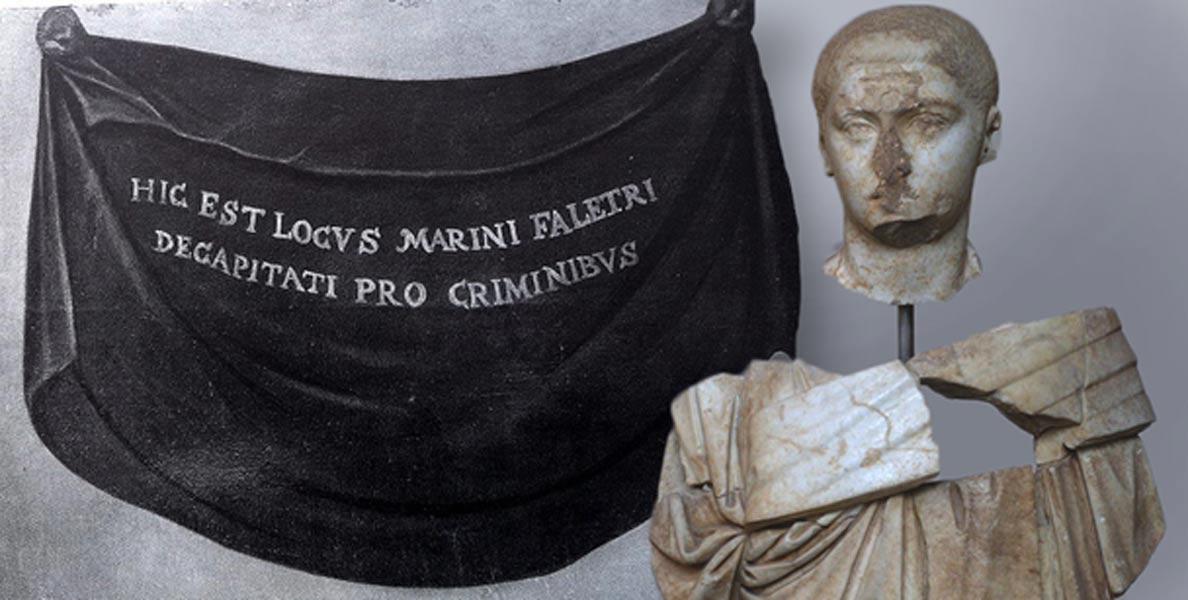

The ancient Roman decree of damnatio memoriae (“damnation of one’s memory”) was a mark of great disgrace and a punishment, deemed worse than execution, for an ancient Roman. The object of the punishment was to cancel every trace of the condemned person from the life of Rome, as if they had never existed, in order to preserve the honor of the city. The methods involved, but were not limited to, scratching the name of the condemned person from inscriptions, abusing the statues of the person, mutilating or painting over their likeness and destroying results of their labor such as writings, buildings and so on.

From a modern perspective, we may not fully grasp the gravity of this punishment – We know that only very few people are remembered long after their deaths, and fewer still would have the luxury of having wax masks or likeness of themselves. Therefore, there has to be something more to this practice than mutilated likenesses and erasures of the person’s name from public registers. To investigate, one can start with isolating two events that warrants this practice in the period of the Julian Emperors of Rome, specifically under the rules of Emperors Tiberius and Emperor Claudius.

What a Person Can Do to Warrant Damnatio Memoriae

Before we get carried away, it is useful to briefly look at the specifics are behind damnatio memoriae itself and what one would need to do to earn such a punishment. Damnatio memoriae was normally reserved for those such as Senators and Emperors whose acts did not reflect well on Rome as a whole, or those who committed treason or brutality which put Rome in danger or disgrace. However, there were also many instances where emperors' memories were censured because of conflicts with the senatorial aristocracy, with rival claimants to imperial power or with the army, without having much to do with the Roman public.

- The Madness of Caligula

- Questioning the Dramatic Story of the Empress Messalina, Was She a Cruel Doxy or the Victim of a Smear Campaign?

- Exposing the Secret Sex Lives of Famous Greeks and Romans in the Ancient World

Among those who suffered damnatio memoriae in the Julian period were Lucius Aelius Sejanus, who had conspired against Emperor Tiberius in 31 CE, Cnaeus Calpurnius Piso, a senator accused of treason as well as the murder of the Tiberius’ nephew and heir, and Germanicus, was also a victim of this practice. Although the senate could vote for a condemnation of a person’s memory, the Emperor had the right to veto. For instance, when the senate wanted to condemn the memory of Caligula, the Emperor Claudius prevented this. Nero was declared an enemy of the state by the senate, but then was given an enormous funeral honoring him after his death by Vitellius.