Alexander the Great: Bleeding Asia Dry – Part II

A famous Roman aphorism was used well by Tacitus: “They plunder, they slaughter, and they steal; this they falsely name Empire, and when they create a desert, then they call it peace”. It is a disillusioned speech from a later age which could have been written in hindsight of Alexander’s Macedonian campaign in Asia. At Alexander’s death in 323 BC his bodyguards and leading generals had to pick up the pieces and govern a new regime that had toppled centuries of established Persian rule and a tax collecting system that once had stretched from the borders of India to the Mediterranean.

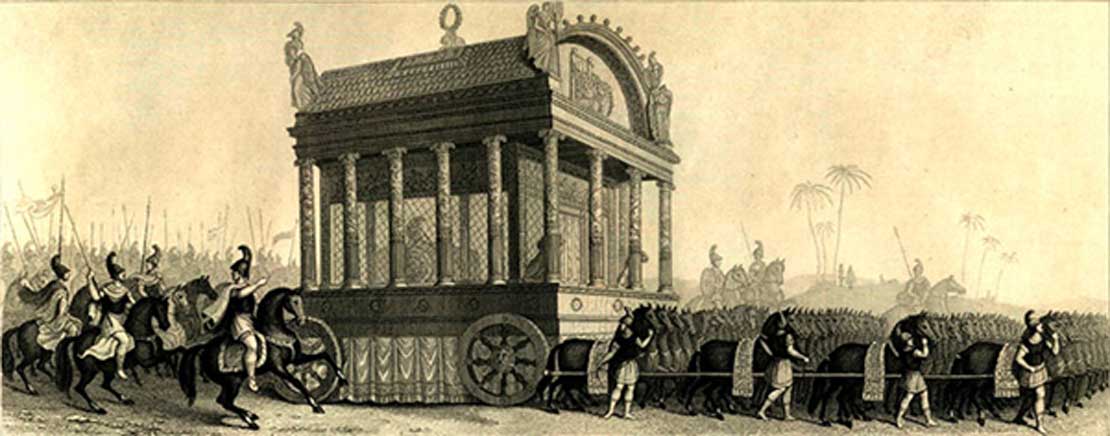

Alexander’s funeral bier, pulled by 64 mules, on the way from Babylon to Damascus (Public Domain)

Dividing the Empire

With Alexander’s passing, the civilized world, which had never before known only one king, now found itself in the position of having no functioning king at all. Additionally, as events were to prove, Alexander’s former bodyguards in particular, were too authoritative in their own right to be subservient to their peers. The top echelon of Alexander’s command, alongside the foremost infantry officers at Babylon, had voiced their ambitions and prejudices, disguised as advice on future governance, at the Assembly of Macedones, convened to decide the fate of the empire. What finally departed from Babylon was an army held together by resented compromises and badly veiled accords. Although alliances of necessity would pockmark the Successor Wars, they were forged only to preserve the independence each general had achieved and to bring down a mutual threat.

When we consider the distribution of Alexander’s empire at his death, an impartial read of the list of appointed satraps, with its 24-plus governors answering to no clear local hierarchy structure, transmits the inevitability of fragmentation. It was a fate underlined by the propaganda of Alexander’s prediction of posthumous funeral games to be fought over supremacy. Regional administration of the Asian empire would have been further complicated by the divided responsibilities of satraps, garrison commanders and citadel officers-cum-treasurers, with their reporting lines to absent child kings and a roving grand vizier, a role held briefly by Perdiccas, Alexander’s former second-in-command.

The kingdoms of Alexander’s successors after 301 BC (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Beyond Extravagance

The theme of the years either side of Alexander’s death was uncertainty, both in Greece and Asia. The Persian Empire at its height had enjoyed an annual income equivalent to 30,000 talents, and sources suggest Alexander and his new order spent over 50,000 talents, equivalent to 50 years of Athenian total revenue, in his extravagant last two years. Some 10,000 had repaid soldiers’ personal debts, gold crowns were handed out to generals at Susa and a further 10,000 talents paid off veterans, with a similar sum destined for temple restoration in Greece; presents, weddings, dowries and a research grant of 800 talents to Aristotle added to the bill, as well as payments to orphaned children and their promised education.

The compliant rajah of Taxila had even been given 1,000 talents and Harpalus had fled to Athens with a further 5,000 from the treasury, equating to some 140 tons in silver or 14 tons of gold, which alone, if in gold, would have required a minimum of 30 ships to transport it. In comparison, Alexander’s sacking of ancient Thebes in 336 or 335 BC had apparently only yielded 440 talents, though this number probably related to the sale of prisoners alone.