The Rage of Horemheb: Hurried End of Akhenaten, Aye and Atenism – Part I

Barely four years after the death of Nebkheperure Tutankhamun in 1323 BC, the powerful ruling family was overthrown by Horemheb, a general and one-time non-royal crown prince; ending the Thutmosid line - and later, the Eighteenth Dynasty itself - that had lorded over Egypt and taken her to heady heights over a span of 250 years. Religious upheaval, glaring nepotism and corruption among the ruling elite had very nearly destroyed the glory of the empire. But, Horemheb would soon learn that the path to become pharaoh was fraught with great peril and challenges, in the form of political machinations by a powerful contender, Aye, and much drama at the royal court.

A painted limestone relief from the Memphite tomb of Horemheb shows him seated before an offering table. This elaborate sepulcher was built when he was a Generalissimo; the uraeus on his brow was added after he became pharaoh.

Horemheb Ascends to Greatness

Following the sudden demise of the boy-king Tutankhamun, two individuals who had played pivotal roles in the aftermath of the Amarna interlude rose to become pharaohs in quick succession—Kheperkheperure Aye and Djeserkheperure Setepenre Horemheb. Several Egyptologists opine that a power struggle arose between the two formidable friends-turned-foes, after Neferkheperure-waenre Akhenaten’s stab at monotheism failed. Horemheb, the last king of the Eighteenth Dynasty who saved the empire from the brink, came to the throne around 17 years after the Heretic’s death: Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten Smenkhkare-Djeser-Kheperu or better known as Akhenaten (three years), Tutankhamun (10 years) and Aye (four years). The Amarna fiasco was still fresh in the minds of the populace.

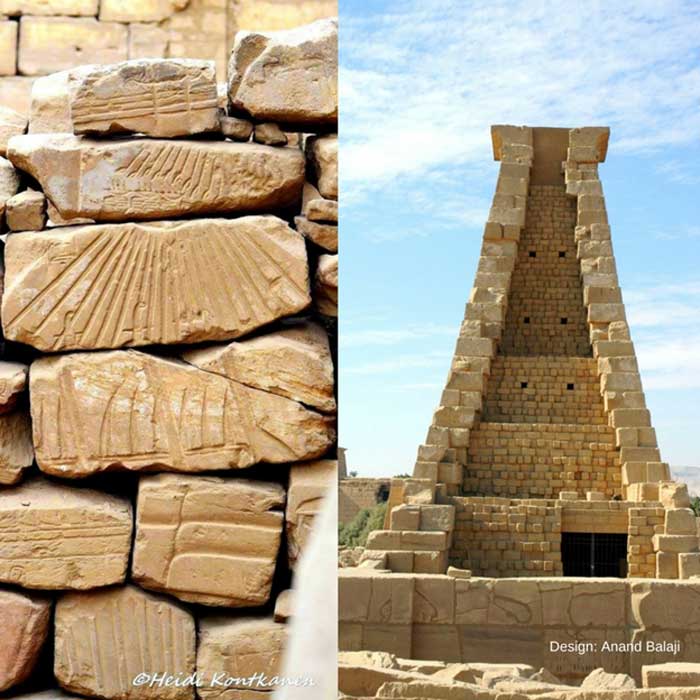

Thousands of Talatat lie in the precincts of Karnak Temple today. It will take a Herculean effort to piece together this massive Amarna-era jigsaw puzzle. However, we have learned much from many assembled blocks. (Right) The Ninth Pylon built by King Horemheb using Talatat blocks from Akhenaten’s structures as fill. (Photo: Francesco Gasparetti)

The erstwhile Generalissimo, Horemheb, was largely successful in expunging the names of Amarna kings from the records. He did so with an undeniable vengeance and in haste. And in doing so, he sent a clear message that the crown would not tolerate an affront to Ma’at. Two decades after Akhenaten’s death, all vestiges of his era were obliterated. The unforgiving desert sands did the rest, and soon swallowed the last traces of Akhetaten, his palace.

“Horemheb usurped the monuments of his immediate predecessors Ay and Tutankhamun. To the two great 'Restoration' stele that detailed the good works of Tutankhamun he simply added his own name. Embellishments were carried out at the great temple of Amun at Karnak where he initiated the great Hypostyle Hall and added a tall pylon, No. 9. Here he achieved two objects: first, he built the pylon to the glory of Amun on the south side of Karnak; and secondly, he destroyed the hated temple of the Aten erected by Akhenaten by simply dismantling it and using its small talatat blocks as interior filling for the hollow pylon. Archaeologists have recovered thousands of these blocks during the restoration of the pylon and have been able to reconstruct great Amarna scenes. In one sense, therefore, Horemheb's destructive scheme backfired: by hiding the blocks in the pylon he preserved them for posterity,” observes Peter Clayton.

This limestone pilaster depicts Horemheb with his hands raised in prayer. The Generalissimo’s first tomb in Saqqara was destined never to be utilized, for he died a pharaoh, and as was his prerogative, chose the Valley of the Kings as his burial site.