Terra Australis The Fabled Continent Of Antiquity’s Antipodes

For nearly 2,000 years, right up until Captain James Cook’s second voyage to the Pacific in 1775, geographers debated the existence of Terra Australis, a mythical landmass to the south-east said to be the fifth and final continent of the world. Known variously as Terra Incognita, Oceano Oriental, Mar del Sur, Mare Pacificum, and Zuytlandt, this hypothetical region was first pondered by Greek scholars convinced it acted as a counter-balance to the oikoumene, the known and inhabited territories of Europe. By the 15th century, following innovations in seafaring technology, Europeans were finally able find out if the theories advanced by their ancestors were correct.

Pythagoras, ancient Greek philosopher. From Thomas Stanley, (1655), The history of philosophy: containing the lives, opinions, actions and Discourses of the Philosophers of every Sect (Public Domain)

The Concept Of Terra Australis

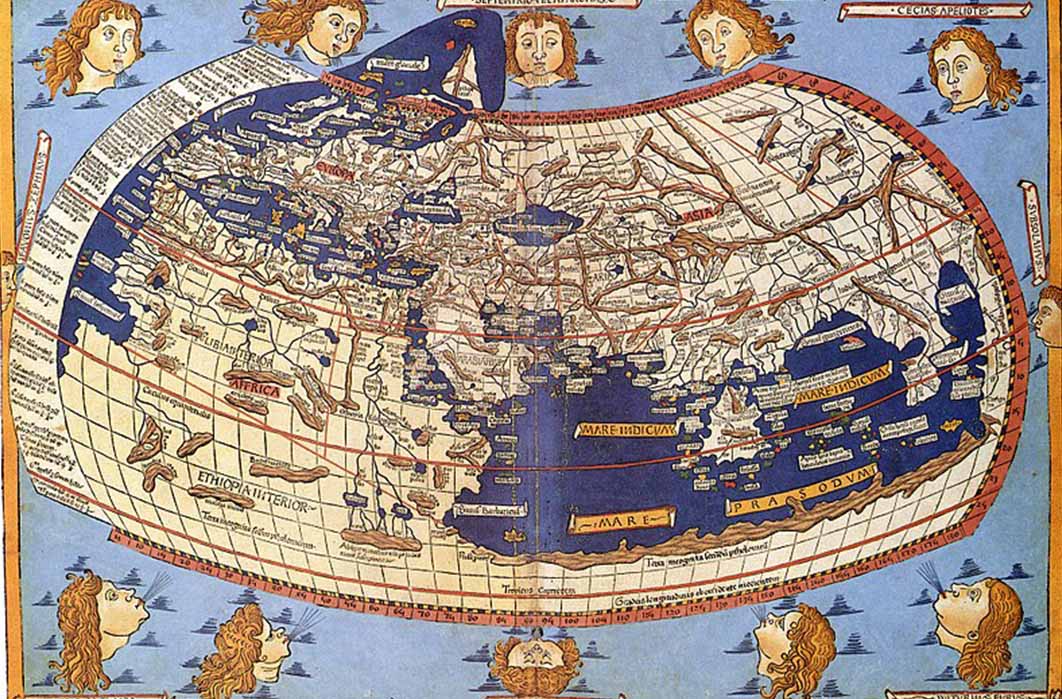

The notion of Terra Australis originated in the sixth century BC, when Greek mathematician Pythagoras concluded that the earth must be a sphere like the sun and moon. His successor Aristotle continued to contemplate the question, reasoning that the presence of a continent located in the south-east, outside of the oikoumene, would provide the necessary balance that a spherical earth needed, in order to stay at the center of the universe. This hidden realm, which he named the Antichthon, was a concept that was further developed by later scholars such as Roman statesman Cicero and Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy.

On the other hand, the idea of an untouched fifth continent that provided equilibrium to a globular Earth was heavily criticized by early Christians, who maintained that the earth was in fact a disk surrounded by water. Saint Augustine in the fifth century was a notable detractor, particularly offended by the assumption that the Antichthon also housed the descendants of Adam and Eve. With no mention of the Antichthon in holy scriptures, Augustine stated that even if there were living beings, that he would still consider them outsiders to Christianity.

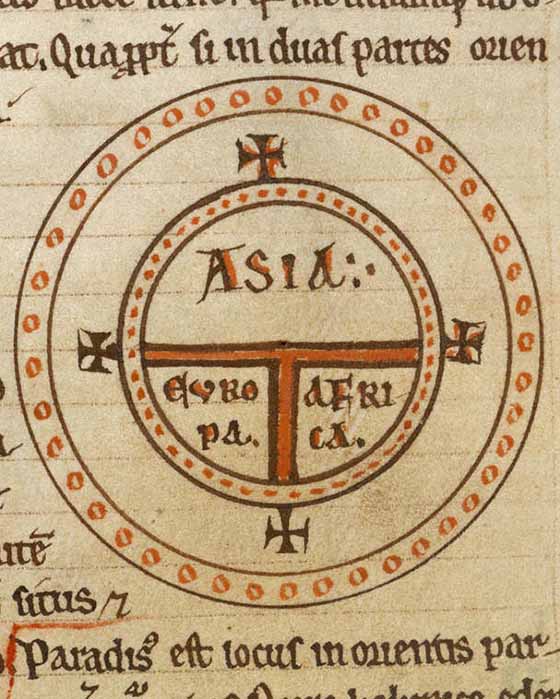

The medieval T-O map represents the inhabited world as described by Isidore in his Etymologiae. (Public Domain)

In contrast, Isidore of Seville, the seventh century savant, was more open-minded, taking the idea of Terra Australis much more seriously. Isidore theorized that the world was divided into four parts, the last of which was situated in the southern reaches of the map: “unknown to us because of the burning sun”. According to him the Antipodes, a lost branch of humanity, were said to live in this impassable land of scorching heat.

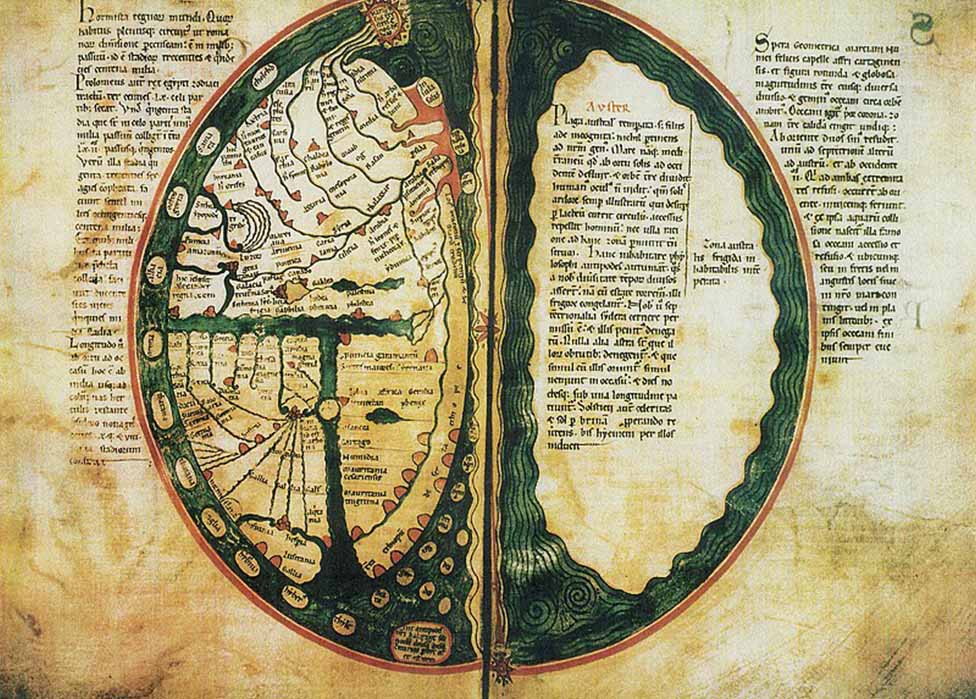

A map in the Liber Floridus Lambert of Saint-Omer oriented with east on top, depicting the known world (Asia, Europe, and Africa) to the left, and Terra Australis to the right (1120) (Public Domain)

Terra Australis Mapped

Belief in Terra Australis persisted throughout the Middle Ages, prominently featuring in the eighth century maps of Spanish monk Beatus, drawn up alongside his gloomy interpretation of the apocalypse. The earliest copies of his work depict a southern continent called ‘Deserta terra vicina solida ardore incognito nobis’, a characterization inspired by Isidore, which meant ‘a deserted neighboring land, hardened by heat, unknown to us’.