Historical Journey of the Dying Gaul

The 2,000-year-old sculpture of the Dying Gaul is a larger-than-life marble sculpture of a nude man on the ground holding himself with one arm, resting weakly on an outstretched leg. His hand sits atop a broken sword on the ground and his head bent downward, the man is dying from a chest wound. The statue has been rediscovered in the early 17th century during excavations for the Villa Ludovisi, commissioned by art connoisseur Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, which was built on the site of the ancient Gardens of Sallust on Rome's Pincian Hill.

Origins of the Sculpture: Exploring the Hellenistic Roots

The Dying Gaul is first mentioned in the Ludovisi collection's 1623 inventory, when it is characterized as a dying gladiator instead of a dying Gaul, but at around the turn of the seventeenth century, experts came to recognize that the image represents a Gallic warrior. The torque around his neck, his moustache, and his leonine hair all indicate that he belonged to one of the Celtic tribes that the ancient Greeks and Romans regarded as barbaric. Therefore, for both the Romans and the Pergamene Greeks, the theme of the statue was civilization's triumph over barbarism.

Detail of the head of the Dying Gaul. (Rabax63/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The sculpture that we see today are Roman replicas of Greek bronze originals made in Asia Minor in the third century BC by the Hellenistic sculptor Epigonos to commemorate the king of Pergamon's triumph over the invading Gauls. The sculpture, created between 100 and 200 BC, is a Roman copy of a lost bronze Greek original created nearly a century earlier. The original statue was most likely installed in Pergamon's Sanctuary of Athena, the city's patron goddess. The Greek bronzes were later transported to Rome, presumably by Emperor Nero, to remind Romans of their own heroic conquest of Gaul.

- Caesar’s Gambit: Reliving the Drama of the Gallic Wars

- Gaul’s Solar Alignment: A Secret Deeper than Rennes-Le-Chateau

The Dying Gaul and the Image of Death in Ancient Greek and Roman Art

Homer has given his readers a very sensual understanding of the concept of death. Nobody understood death like Homer did in his description of a human’s slow descent into death, or as Homer wrote, "dearer to the vultures" than to loved ones (Iliad, book 11), and "dropping to the world of night" (Iliad, book 16). Homer depicts death replacing life both instantly and millimeter by millimeter. His poetry depicts spears piercing armor, rending cloth, entering flesh, penetrating viscera, severing veins, piercing bone, marrow giving way, and swords cutting all the way through bodies into the dirt below. Homer’s death scenes were descriptive, direct, and detailed, without the use of the romance of salvation, thunderbolts, or even florid poetry characteristic to Roman writers.

While Dying Gaul that we know now is a Roman imitation, the statue’s true meaning is still very much Greek. Ancient Greek art was not as theatrical as Roman art, concerning itself more with philosophical structure and restrained sensuality. The Dying Gaul depicts someone in a slow process of death as his soul yields to the physical. Removing any allusion of hope, this is not the huge drama of a man rising valiantly against death. There is nothing heroic, no final outburst of vengeance or Roman patriotic self-sacrifice. In this statue, nothing accumulates against death.

- Battle of the War Gods: Ares versus Athena! Understanding Ancient Greek War Deities

- Worshipers, Rule-Breakers and Champions: Women and the Ancient Greek Olympics

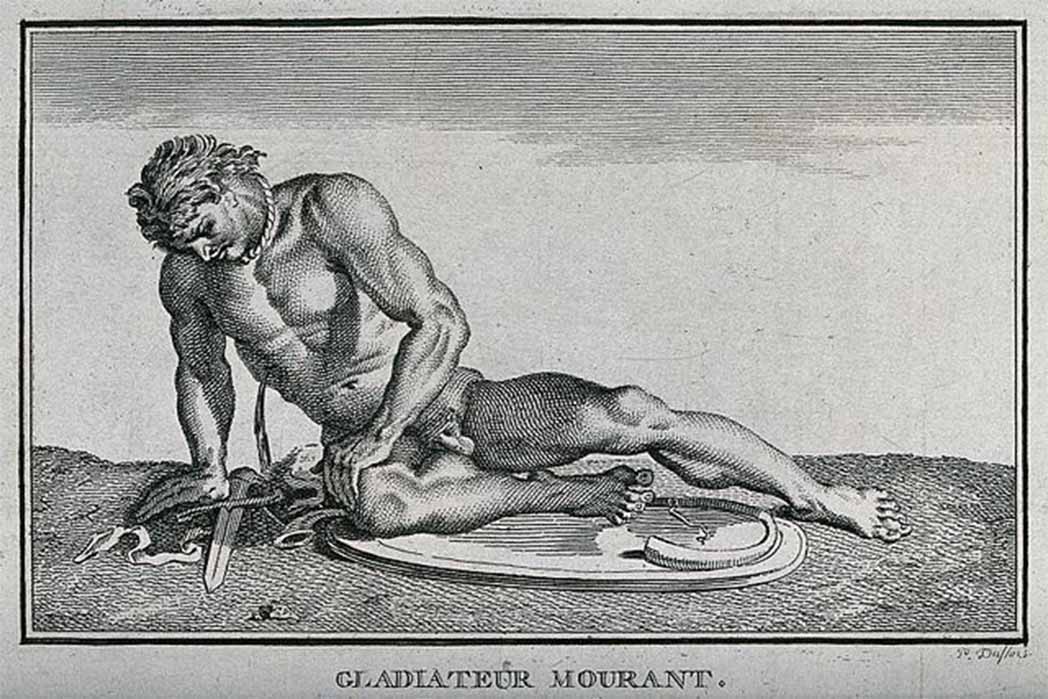

Line engraving of a fatally wounded gladiator kneeling on his shield while blood gushes from the wound in his side, by P. Duflos. Iconographic Collections. (Wellcome images/CC BY 4.0)

Pergamon and the Gauls

As Pergamon was a melting pot of multi-cultural populations and groups from many regions of the ancient world, it played an essential role in the development of various arts. Because of the ongoing maritime trade, artistic creativity did not stop at the borders of the city, and instead spreading from one distant location to another.