The Byzantine Emperors 395 – 491 AD

The Byzantine Emperors witnessed the disintegration of the western Roman Empire which did not survive past the fifth century. Contrary to the latter, the Byzantine Empire would subsist the successive waves of Germanic invasions to endure for another thousand years.

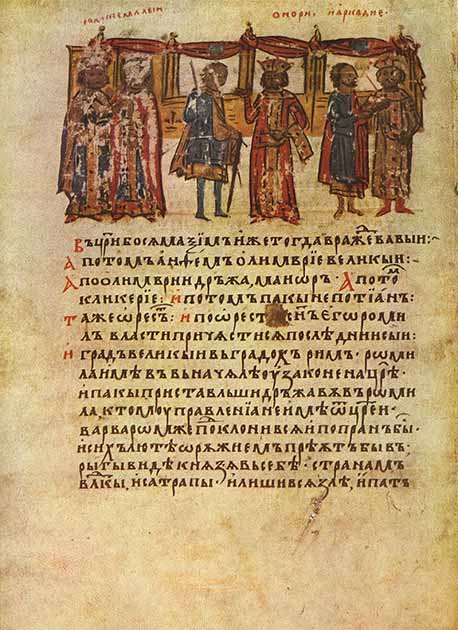

During his reign, Emperor Theodosius I (379–395 AD) succeeded in mitigating the disastrous aftermath of the Roman defeat of Adrianople of 378 in the hands of the Visigoths during which his predecessor, Valens was killed. Unable to defeat and expel the Visigoths out of the Empire, Theodosius I eventually reached a compromise by granting them the status of foederatus, officially recognizing them as an equal and independent ally of Rome. In exchange for territory within the Empire that was now theirs, the Visigoths owed military service to the Empire. In 394, Theodosius I led his army to the West, to overthrow the usurper Eugene. At the Battle of Frigidus, the western Roman army was routed, but at a high cost to the eastern Roman army. Following the battle, Eugene was executed, and the Roman Empire was again reunified into a single political entity. Five months later, Theodosius I died in Mediolanum (Milan, Italy), leaving the Empire divided between his two sons. Honorius would rule the West while Arcadius would rule the East.

The Emperors Arcadius, Honorius and Theodosius I (12th century) Manasses Chronicle (Public Domain)

Emperor Arcadius and Empress Aelia Eudoxia (395-408)

Arcadius was the eldest son of Theodosius I and Aelia Flavia Flaccilla. When his brother Honorius was born in 383, Arcadius was named Augustus, or co-emperor, at the age of six. When Theodosius I died, Arcadius, then aged 18, succeeded him as head of the Empire in the East, while his younger brother Honorius, aged 12, who also had been appointed Augustus in 393, assumed the same role in the West. This division of the Empire into two political poles resembled others of the same type in the past, but this time it was significant because it was the prelude to the definitive division of the Roman world. From that point on, the socio-political evolution that characterized each part of the Empire was to follow different paths.

Despite his maturity, Arcadius did not hold the reins of power. Whether because of his lack of experience related to his youth or the weakness of his character, authority was in the hands of his principal minister and Praetorian prefect, Rufinus, already in the position under Theodosius I, and the court chamberlain, Eutropius. Rufinus, although very capable of governing, had a reputation for being unscrupulous, ambitious and a miser. Planning to increase his influence on Arcadius and expand the territory of the East at the expense of the West, he soon entered into conflict with Stilicho, his western counterpart and regent of Honorius, who had the same aims, but this time in favour of the West. Moreover, Stilicho claimed that Theodosius I, before his death, had given him the charge of watching over his two sons and the Empire. In reality, Stilicho’s aim was the annexation of the eastern Empire’s labour-rich Prefecture of Illyria (region roughly covering modern Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Albania, Macedonia and Greece) to the western Empire.

- The Fall Of The Western Roman Empire - A Military Perspective (405-455 AD)

- A Millennium of Glory: The Rise and Fall of the Byzantine Empire

- East vs. West: The Untold Story of Christianity's Great Schism

At the centre of this conflict was a player whose importance would only increase and who would soon make history in a sinister way for the Romans. He was Alaric, the King of the Visigoths. Since 382, the Visigoths had federated status. But shortly after the death of Theodosius I, the federated Visigoths under Alaric’s leadership revolted and ravaged the Balkans. Athens was sacked. The situation deteriorated in the East when, at the instigation of Stilicho, Rufinus was assassinated. Authority then reverted to Eutropius. Wishing to keep Alaric’s Visigoths away from Italy, around 397, Stilicho fought him in Greece, but despite his victory, Alaric managed to escape. Some historians have suggested that Stilicho may have deliberately let him escape in order to keep Alaric in the East and thus harm the interests of Constantinople. As a revolt broke out in Africa against the authority of the West, Eutropius declared the western general-in-chief a public enemy. He also appointed Alaric, who probably could not be driven out of the East, master of soldiers in the Balkans in order to calm his ambitions. In the West, this double insult caused consternation.

Steelyard weights often took the shape of busts of Byzantine empresses. This unusually detailed image may depict an empress of the Theodosian dynasty, which ruled from 379 to 450. Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

In 399, Stilicho managed to use shenanigans to overthrow Eutropius. Contrary to what one might expect, power still did not fall to Emperor Arcadius. Rather, it was his influential and impulsive wife Aelia Eudoxia who assumed that role after proclaiming herself Augusta. In 401, she decided to act against Stilicho by urging Alaric to invade Italy in the name of the East. Alaric was defeated by Stilicho at Pollenza in 402, then again at Verona in 403, but again managed to escape. The following year, Aelia Eudoxia, who had already given birth to a first son with Arcadius in 401, called Theodosius II, died of a miscarriage. The government then fell into the hands of the Praetorian prefect Anthemius. His grandson was to become the future western Roman Emperor of the same name who would rule from 467 to 472 AD.