Formidable Byzantine Roman Empress Theodora - Saint Or Sinner?

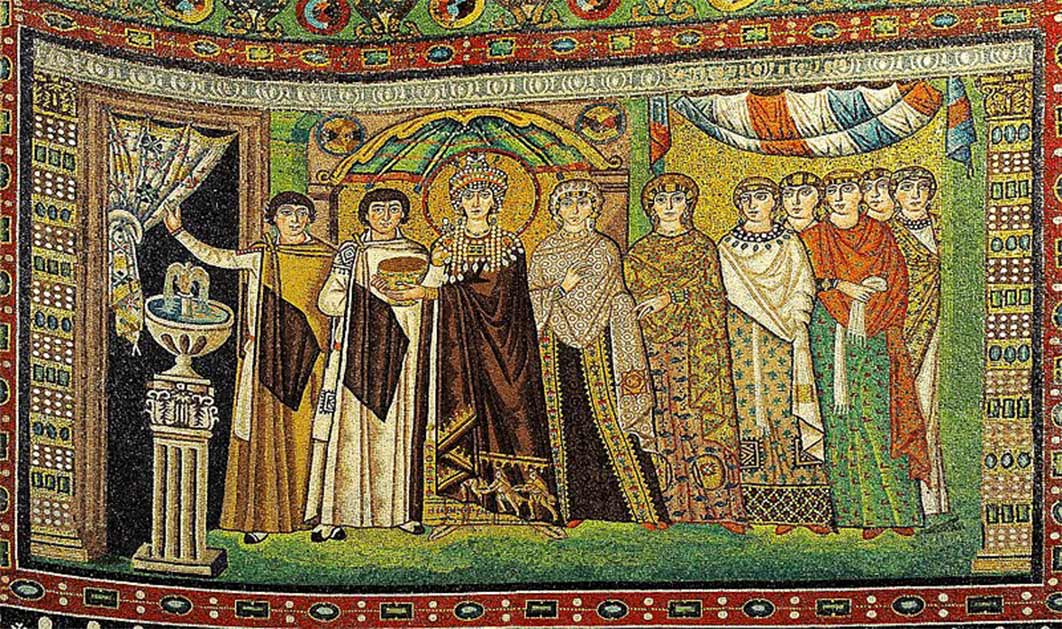

The hooded gaze of an inscrutable Theodora (c.497- 548 AD) greets hundreds of thousands of visitors each year as they pay their respects to her mosaic at the Basilica of Saint Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Encircled in glittering gold and bedecked in crown jewels, her visage befits the powerful Byzantine Roman empress she once was. More partner than figurehead, Theodora is considered to have been one of the most powerful and influential of all empresses. Yet while her image on the mosaic is discernible, due to the incoherent misogynist and classist ramblings of an ancient chronicler the image she presents to history is somewhat less so. Alas, much of what is known about Theodora comes from the poisonous pen of Procopius of Caesarea, a primary Justinian (483 - 565 AD) historian. Prior to Anecdota or Secret History, Procopius had written nothing but praise about the Justinian administration, so the book came as something of a surprise to the academic community when it was re-discovered centuries after it was written in 550 AD. Brimming with hyperbole and invective against the royal couple whom Procopius characterizes as “demons,” Secret History, at times, reads like the tabloid press. No character, however, is more impugned than that of the empress. Like all ancient chroniclers when reporting about powerful women, Procopius focuses on her sexuality. He repeatedly refers to the time—-when as a child and young adult—-she performed on stage and engaged in the oldest of professions. But according to Procopius, licentiousness was not her only sin, she was also cruel, spiteful, vindictive, and tyrannical. Regrettably, Procopius’s fiery invective against Theodora has influenced subsequent historians who have let his slander cloud their judgment on this complicated empress.

Young woman Contemplating, with a mask lying at her feet by Benjamin-Constant (Public Domain)

Raising Theodora

Notwithstanding, Procopius’s poison pen, who was Empress Theodora? While her work in the sex trade is unconfirmed, her humble origins are not. In an era not known for social mobility, how did the daughter of a bear keeper rise to the highest office in the land? And why was her reign in many ways more remarkable than that of her husband, Justinian?

Her father’s death when she was five years old left her family in desperate need. Although her mother quickly remarried, when the bear keeper post vacated by her late husband was denied to her new husband, the family remained financially in the lurch. Because employment options were few and far between for females of any age in sixth-century Constantinople, Theodora’s mother had to be resourceful—a trait Theodora must have inherited. She encouraged her three daughters to perform on stage as mime actresses. Yet, in the minds of Byzantine society, there was a stigma attached to acting. Because its focus was on the “sins of the flesh” — theater was considered the quintessence of depravity.

L'Imperatrice Theodora au Colisée by Benjamin-Constant (Public Domain)

To be sure, there was little difference between actresses and prostitutes, and both were outcasts from society. When she reached “maturity”—likely at the tender age of 12—Theodora officially began her acting career. Although his account may be less than reliable, Procopius casts aspersions on the tender-aged Theodora for playing the role of victim when he claims that once she reached puberty “and at last was ripe for it, she joined the women on stage and promptly became a prostitute.” Procopius, however, could only know about her work as a prostitute by hearsay since he himself was a child at the time. Be that as it may, with her quick wit, good looks, and precocity, she soon achieved notoriety as a comic actress, capturing the attention of men of means.

- Sex and the Roman Empire: Scandalous Literature about Empresses Euphemia and Theodora

- Did Antonina Use Witchcraft to Enslave the Mighty Byzantine General Belisarius

- History Was A Riot: Fist-Raising, Fire-Setting Revolts

Eventually, she moved out of Constantinople to become the live-in mistress of a wealthy governor (Hecebolus) in Libya. By some reports, Theodora may have even had one or two children by then—though accounts of them are scant. Sometime after the relationship with the governor soured, Theodora, on her way back to Constantinople stopped first in Alexandria, then in Antioch. Many scholars believe it was while she was in Alexandria that she underwent a full religious conversion that not only changed the course of her life but may have changed the course of religious belief in the region as well. Her adopted religion, a branch of early Christianity called Monophysitism argued that Christ had only a divine nature. This belief was at odds with most of the West and the Byzantine state itself which believed that Christ had two natures—both fully human and fully divine. The impact of her religious fervor was far-reaching.