Women’s Wills From Anglo-Saxon Times To Post War Feminists

Since ancient times, wills and inheritance have a long, recorded history and Britain is no different. A history of a thousand years of the wills of women offer a rare but rich glimpse into their often otherwise secluded and unreported lives. Women’s lives and women’s voices are hard to discover in British history books. Until modern times the statesmen and leaders of the nation, soldiers and generals, sailors and admirals, judges, politicians and ambassadors were almost always male. The same is true for those owning the largest estates, stately homes and aristocratic titles, though these often involved a good marriage to a wealthy heiress, but this implied her inheritance was passed by marriage on to other families.

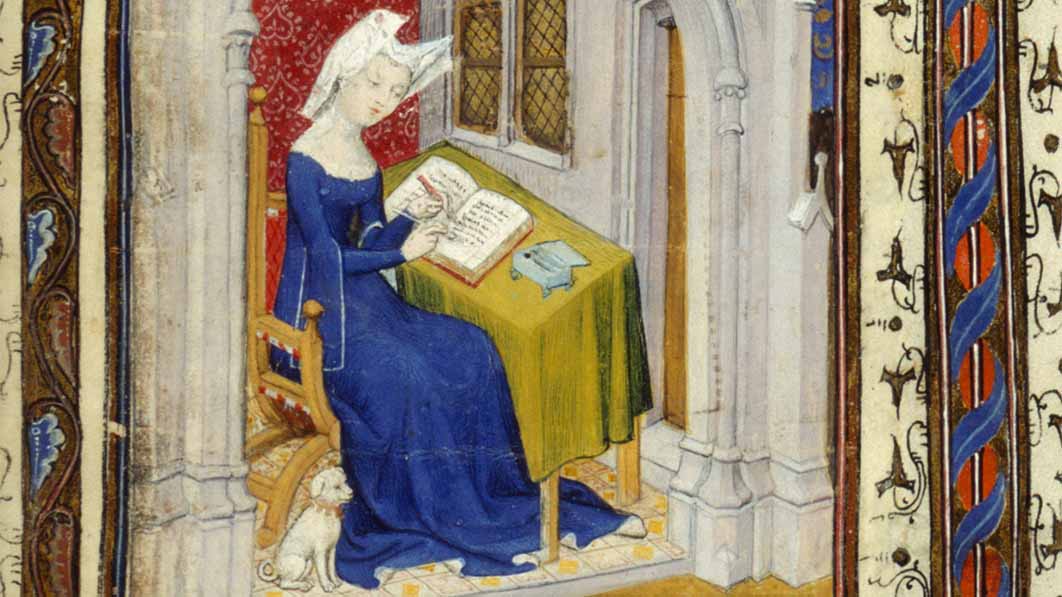

An Anglo-Saxon King and his witan – women were often excluded in history (Public Domain)

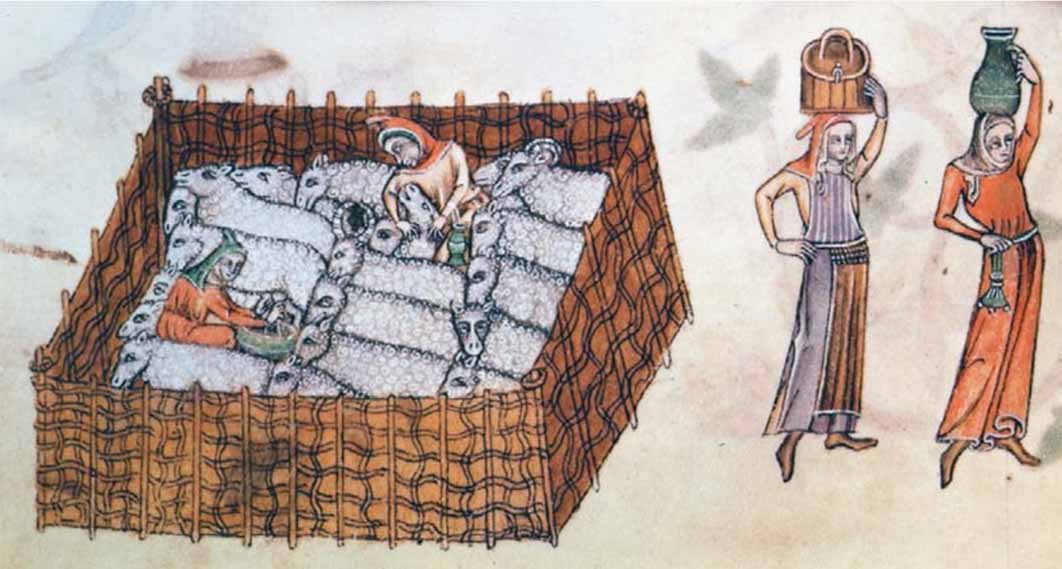

Through their wills the lost voices of women allocating their personal belongings speak up and their wills introduce the recipients of these bequests. Books and a filigree brooch, property and gold, armbands and wild horses, a red tent, household items such as bed curtains, bedding and a holy veil, all of these are mentioned in the wills of Anglo-Saxon women. Recipients including family and friends and loyal servants, the church, priests and even slaves to be manumitted upon the death of the lady, may feature in a Saxon will. Some bequests were extremely valuable, such as farmsteads and estates and livestock as in the year 990 when a wealthy woman Aethelgifu left 20 sheep to the church in Ashwell, Hertfordshire.

An agricultural scene from the 14th-century, by Luttrell Psalter, with a woman milking sheep and two women carrying jars (Public Domain)

The Saxon Will of Wealthy Wynflaed

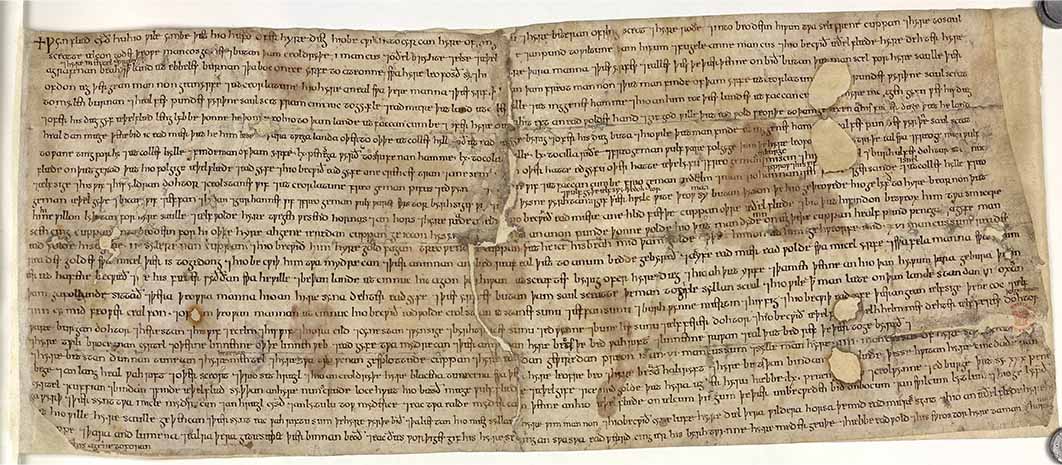

Other bequests carry more personal associations, a remembrance of the person who has died. One of the earliest surviving wills dates from the 10th century in Anglo-Saxon times when such documents were written on parchment or vellum, usually on a single sheet. It belongs to a woman, a widow, by the name of Wynflaed who lived in Dorset in the south of England and died around 960, when the will was written.

Wynflaed owned a large number of slaves working on her farmsteads or in the households of a good many manors, across various counties in the south-east of England. All that remains of the existence of Wynflaed the person and her legacy, is determined from this will, written in Old-English. Some wills were written in Latin. Eventually the language of Wynflaed’s will would form the basis for modern English, but at this early stage, academic experts were needed to translate it, as it differs so much from common English. She probably dictated the will to her priest or possibly a scribe who might have been employed in such a great household. It is believed that the will was first held at Shaftesbury Abbey as the abbey was one of the recipients of important bequests. Bequests were also made to loyal servants and to her family, to her two children and two grandchildren.

The will of Wynflaed (Image: Courtesy of the British Library Board (Cotton Ch VIII 38 folio 1r)