Nova Anglia, The Forgotten Anglo-Saxon Enclave In Ukraine

Tucked away in the outer regions of the Byzantine empire was a pocket of towns with a series of unusual names that have puzzled academic and armchair historians alike, for among the most unexpected of the oddities that dot the antiquated maps of medieval cartographers concerning the Black Sea region, is the surprise inclusion of a town called ‘Londinia’ resting strangely in the north-eastern Crimea. To many, these are merely the remnants of a medieval Anglo-Saxon colony established by a band of English fugitives, who forsook their motherland after being defeated by William the Conqueror and his Norman armies at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. A rip-roaring tale of adventure mostly found within the pages of an obscure Icelandic saga and a dusty French manuscript, this unbelievable story has actually been authenticated by many other historical sources, which attest to an Anglo-Saxon presence in what is now referred to as Ukraine.

The Battle of Hastings

In 1066 following the death of King Edward the Confessor, England was plunged into a succession crisis as three rival claimants, namely the Norwegian warlord Harold Hardrada, the French warrior-baron William of Normandy, and the English king Harold Godwin battled for mastery over the kingdom.

Facing a dual invasion, Harold Godwin first fought against Harold Hardrada, who alleged that the predecessor to Edward the Confessor, King Harthacnut, had pledged him the English throne. Encountering each other at the River Derwent just east of York on September 25 1066, Harold successfully vanquished the Scandinavian marauder with a daring surprise attack at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. With Harold’s own brother Tostig slain, the victory would come at some cost, not least because it also gave William of Normandy enough time to establish a secure base of operations in the south of the country.

The Battle of Stamford Bridge, from The Life of King Edward the Confessor by Matthew Paris.( 13th century) Cambridge University Library (Public Domain)

On the evening of October 13 1066, Harold and William’s armies, camped within sight of each other at a hill located around seven miles (11 kilometers) from the town of Hastings, and made their final preparations for a showdown that would determine the fate of the realm. In the early morning hours of October 14, Harold’s battle-weary warriors, mainly infantry brandishing devastating two-handed axes, arranged themselves into a defensive shield wall formation along a ridge that stretched for nearly half a mile, as William organized his ranks, composed of men from Brittany, Aquitaine, France, and Maine, at the bottom of the hill in three regiments, with the archers taking the front, the infantry the middle, and the armored cavalry stationed at the back.

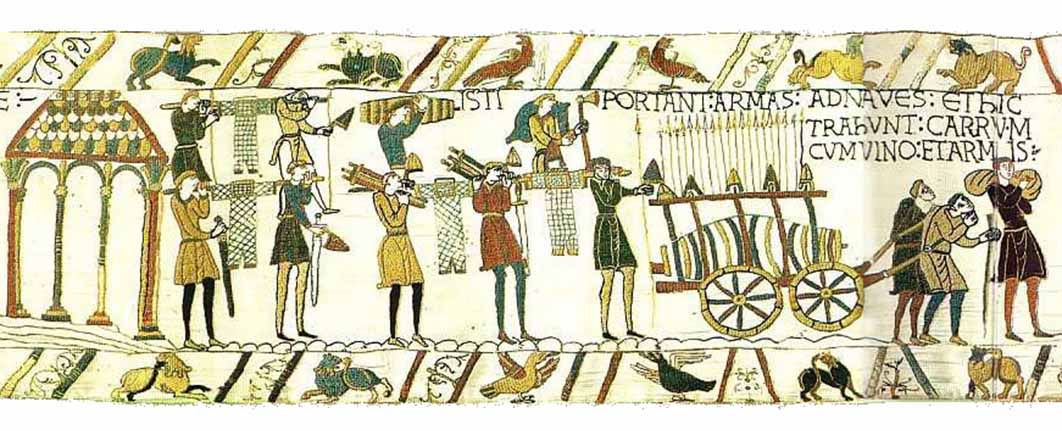

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Normans preparing for the invasion of England (Public Domain)

With both forces numbering 5,000 to 7,000 troops they were by all accounts equally matched when the battle began at 9am to the bloodcurdling sound of war trumpets. Key to Harold’s strategy would be the maintenance of the shield wall, the plan being to absorb the Norman onslaught before going on the offensive, while William would take a radically different approach and work his way up the hill so that his archers were within range and could puncture the English line, which would then be breached by his mounted knights.

- Triumph, Rebellion And The Ancient History Of Ukraine

- Alexander Nevsky – Medieval King Turned Russian Propaganda Tool

- Did Harold Godwinson Really Die on the Battlefield at Hastings as the Records Suggest?

Successfully repelling the opening Norman wave with the slashes of their axes, Harold’s army gained the initiative while a portion of William’s soldiers fled the scene after a rumor circulated that the Duke had been killed. Pouncing on the momentary confusion, some of the English charged down the hill but were decimated after William emerged unscathed and raising his helmet, inspired his comrades-in-arms to exterminate the incoming Anglo-Saxons by loudly proclaiming: “Look at me! I live, and with God’s help I shall conquer!” (William of Poitiers as quoted by English Heritage).