Horace, the Misunderstood Soldier turned Poet and Creator of “Carpe Diem”

The literary works of Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 - 68 BC), or Horace, spans an extraordinarily wide range, making him one of the central authors in Latin literature. Horace seemed to be just as comfortable writing about love and wine as he was about philosophy and literary criticism. However, the phrase that both best encapsulates Horace’s moral stance and saves him from oblivion, is the phrase ‘carpe diem’ (Odes 1.11.8), which endures well to the modern ages as a slogan on T-shirts and the name of a trendy line of leather goods.

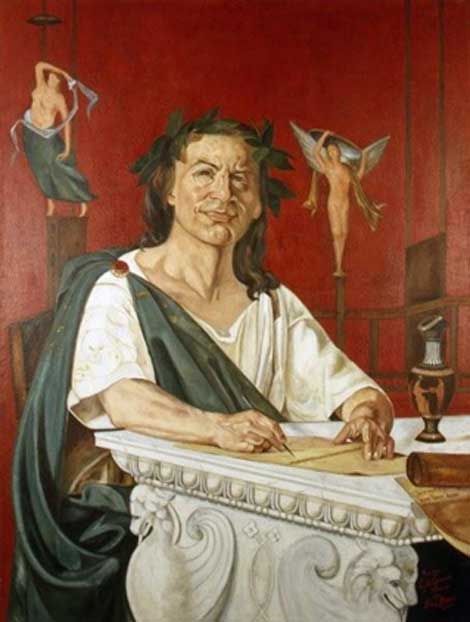

Horace, portrayed by Giacomo Di Chirico (1880s) (Public Domain)

More than a poet, Horace was also a key literary figure in the regime of the Emperor Augustus. Rhetorician Quintilian described Horace’s versatility as being: “… lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.” This very versatility may have been his saving grace as his career coincided with Rome's momentous change from a republic to an empire - a change which would have demanded him to maintain a delicate balance between his old republican friends and his association with the new emperor. This earned him praise by some, yet for others he was described as nothing more than: “a well-mannered court slave”.

To investigate Horace’s experience in this delicate period, the poet himself seems to be the most valuable resource. Consistent with his ambiguity, Horace speaks from each genre as an ‘I’ who is both no-one socially, and a member of the inner circle.

Horace’s Entry into Roman Politics

Horace’s father was a slave who gained his freedom before Horace’s birth. He then went on to become an auctioneer’s assistant. He evidently flourished as he was not only able to own a small property, he could also afford to take his son to Rome and personally ensure that he got the best available education.

So, Horace found himself a student in Athens by 46 BC. Two years later, after the murder of Julius Caesar, Athens came into the possession of his assassins Brutus and Cassius, who clashed with Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew and appointed heir. Horace joined Brutus’ army and evidently made such an impression that he was appointed Tribunus Militum (Tribune of the Soldiers). To put this in context, a Tribunus Militum is a rank just below the Legatus, which was equivalent to a modern high ranking general officer. As young men of equestrian rank often served as Tribunus Militum as a stepping stone to the Senate, this would have been an exceptional accomplishment for Horace who was a mere freedman’s son.

In the rather peculiar absence of the Legatus, Horace and his fellow tribunes commanded one of Brutus’ and Cassius’ legions at the two battles of Philippi - pitting himself against Antony and Octavian. After their total defeat, Horace fled back to Italy, only to find that his father’s farm at Venusia had been confiscated to provide land for Octavian’s veterans.

Cleopatra and Octavian by Guercino (1591–1666) (Public Domain)