Ancient Architecture, Ancient Alcohol, Ancient Religion and the End of Our World

In 1995 a German archeologist named Klaus Schmidt decided to begin work in Turkey at a place called Potbelly Hill, or Göbekli Tepe. He didn't know at the time that he was about to turn the world of archaeology upside down and re-write the story of our civilization. When it became apparent that he was on to something completely transforming, he declared: “In 10 or 15 years, Göbekli Tepe will be more famous than Stonehenge. And for good reason!” He was right.

Ancient Site of Göbekli Tepe in Southern Turkey (Brian Weed/ Abode Stock)

Göbekli Tepe

What he found was a huge temple complex built of immense T-shaped stone pillars arranged in sets of rings. The tallest are 18 feet (5.4 meters) high and weigh 16 tons (14,515 kilograms). Carved into their surfaces are a whole menagerie of bas-relief totemic animals of prey. Littering the nearby hillside are thousands of flint tools from Neolithic times—knives, projectile points, choppers, scrapers, and files.

When Schmidt used standard, accepted methods to date the site he amazed even himself. Göbekli Tepe was built many thousands of years before the Great Pyramid of Giza, way earlier than even the first wooden beginnings of Stonehenge, and, it was then thought, way before the invention of agriculture. How could a work force consisting of the thousands of laborers needed to construct such a project possibly be mobilized, instructed, equipped, fed, and encouraged to stay on the job when the only people thought to have lived back then were stone-age primitives?

So far, there is no indication whatsoever of extensive agriculture going on in the surrounding area until after construction began. At least at first, evidence suggests, hunting teams would fan out, kill what game they could, and bring it back to the workers. The bones of their evening meals consist mostly of aurochs and gazelles. Then, later in the project, it appeared that the birth of agriculture started here, in Turkey, rather than down south at Sumer many thousands of years later as traditional history would claim it did.

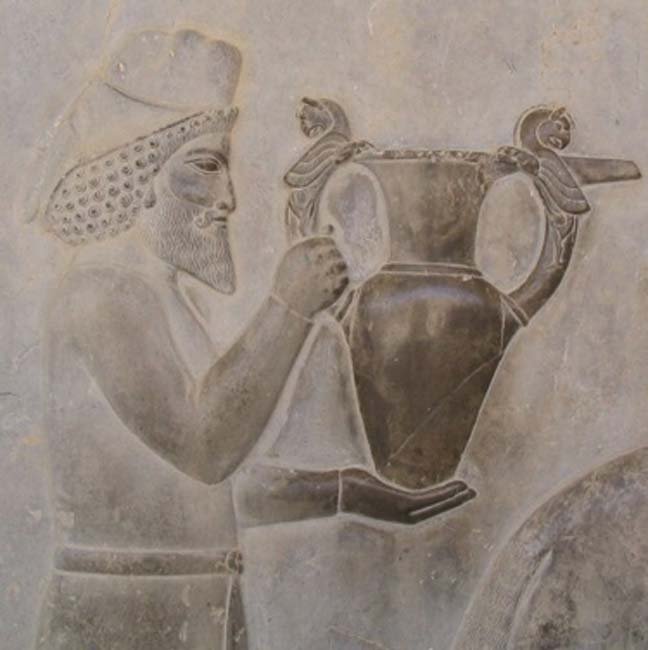

Detail of a relief of the eastern stairs of the Apadana, Persepolis, depicting Armenians bringing an amphora, probably of wine, to the king. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ancient Alcohol

The first harvest of domesticated grain heralded the birth of agriculture, as well as the birth of the alcohol industry, because at least part of that harvest was set aside for the first batch of beer that our civilization had yet tasted. One can only imagine a distant artisan ancestor putting down his hammer and chisel at the end of a long day and declaring, "Now it's Miller time!" This isn't such a far-fetched idea. The Bible (Genesis 9:20-21) tells us that after Noah's Ark had landed at Mount Ararat, not far from Göbekli Tepe, the first thing the old sailor did was to plant a vineyard, make some wine, and get drunk.

Workers who built the Egyptian pyramids were paid in rations of beer. It would seem that those who first told the old stories about the construction of holy places believed that alcohol, also called, interestingly enough, ‘spirits’, and the human race go way back together. To this very day, wine lives on as a central part of Christian services as well.