Mockery of the Crucifixion: The Sacred Donkey and the Cross

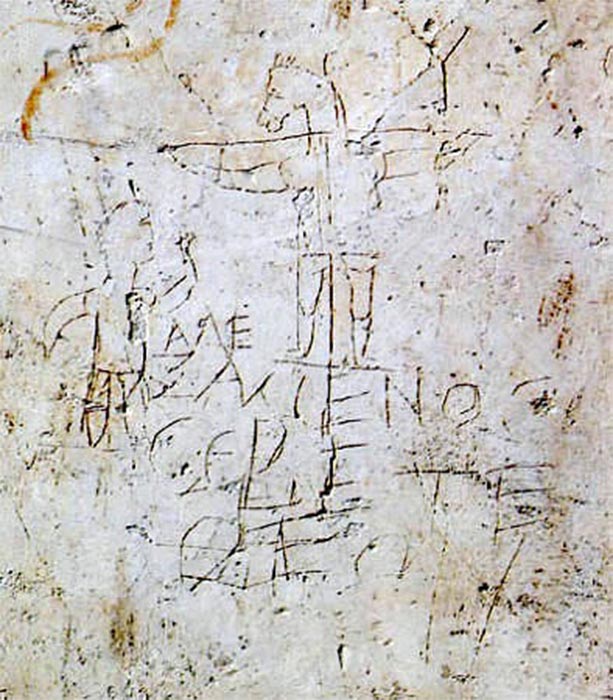

In 1857 in a cell of the ruins of Imperial Palace on the Palantine Hill in Rome, a curious graffiti representing a crucified man (corpus humanum... suffigitur in cruce) but with the head and ears of a donkey (cervix asinina caputque auritu) was discovered. Beneath the sketch was etched in broken Greek: ‘Alexameno worships his God'. Who could have been the instigator behind this primitive, apparent blasphemous mural?

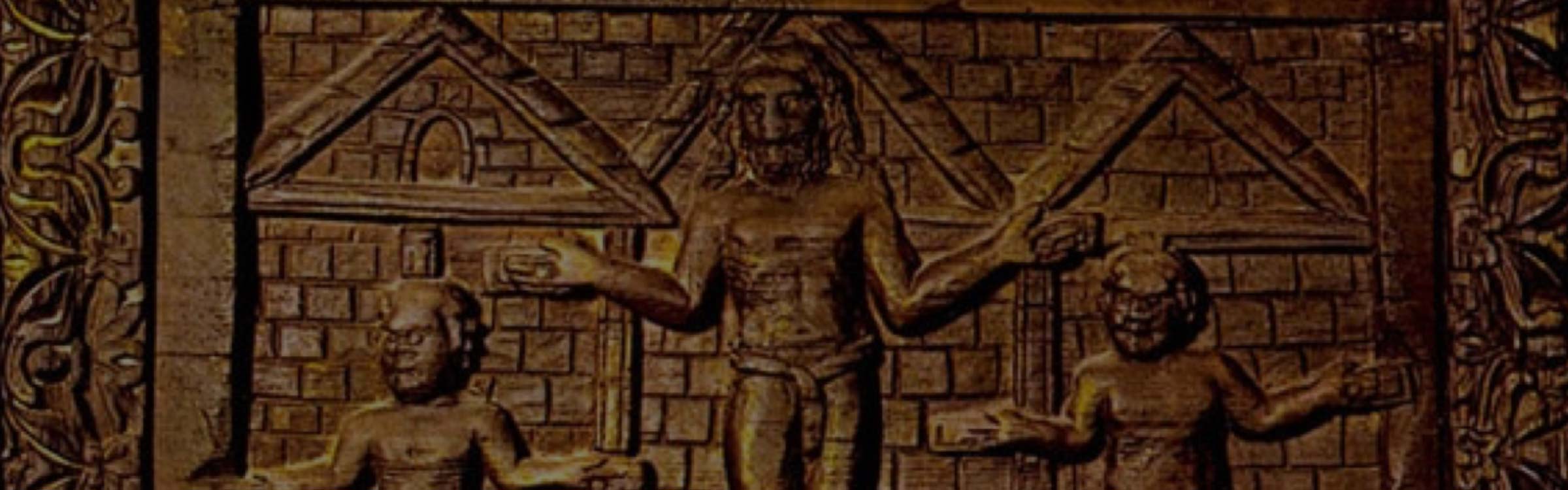

‘Alexameno worships his God' was graffitied next to an image depicting a monophonic Christ. "Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries", by Rodolfo Lancian (1898) (Public Domain)

Careio and Alexameno

In 1903 Giovanni Pascoli dedicated his poetic composition in Latin, called the 'Paedagogium' to a fictional episode that could have occurred in third century Rome, at the Imperial Palace on the Palatine Hill. The cells in the Imperial Palace were actually used to house the princes of foreign kings - captured or given as hostages to Rome - where they were educated according to local customs and cultural canons, including the study of Latin and Roman traditions.

Ruins of Imperial Palace on the Palatine Hill (Johan Haggi/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pascoli imagines that one of these young princes, to whom he gave the name of Careio, turned to a Greek prince of the same age - Alexameno - inviting him to participate in a game, but he was rejected. The disagreement between the two results in a heated quarrel inside the adjacent cells of the two students. Pascoli imagines Careio, offended, desperate and angry, engraved on the wall of his room, for the sake of mockery and complacency (...tunc scribit... et sibi plaudit...), in the language of the antagonist, the phrase beneath the 'blasphemous' drawing. But the question is raised: Was the drawing of the donkey crucifix really 'blasphemous' and then, why choose a donkey?

Detail of Seth (onecephalos) in the act of crowning Ramesses III, from a statuary group. Egyptian museum in Cairo. (CC0)

The Ambivalence of the Donkey in Iconography

As the medievalist Franco Cardini pointed out, the donkey, together with the onager, (an animal of a race of the Asian wild ass native to northern Iran) have always had an ambivalent value in the religious sphere. On the one hand it was a sacred animal to the cruel god Seth; it was considered sacred to Underworld chthonic deities as mentioned by Plutarch in his work Isis and Osiris. According to Patrizia Marzillo: “This divinity (Seth / Typhon)…was Osiris’s and Isis’s envious younger brother. He killed and dismembered Osiris unleashing a long battle with Osiris’s son Horus. Plutarch’s ‘De Iside et Osiride’, the main source for this myth, tells us that because of (Seth)Typhon’s ability to impede the course of progress towards good, the Egyptians assigned to him the most stupid of all domesticated animals, the ass, and the most savage of all wild animals, the crocodile and the hippopotamus.”