Things: Old Viking Parliaments, Courts And Community Assemblies

Ancient governmental terminology such as monarchy, oligarchy and democracy have been used for more than 2,000 years and have Greek and Roman origin, but in Early Germanic societies, right up to the Vikings of modern Scandinavia and Britain, the word Thing described ancient community assemblies conducted under governance of a local lawmaker, at locations called Thingstead or Thingstow, or in Old English, at þingstedes and þingstōws, respectively. The modern English word Thing, and the German and Dutch word ding, as well as the Scandinavian ting, all mean ‘object’, with an etymology in the Old Norse, Old Frisian and Old English word: þing, which means ‘assembly’.

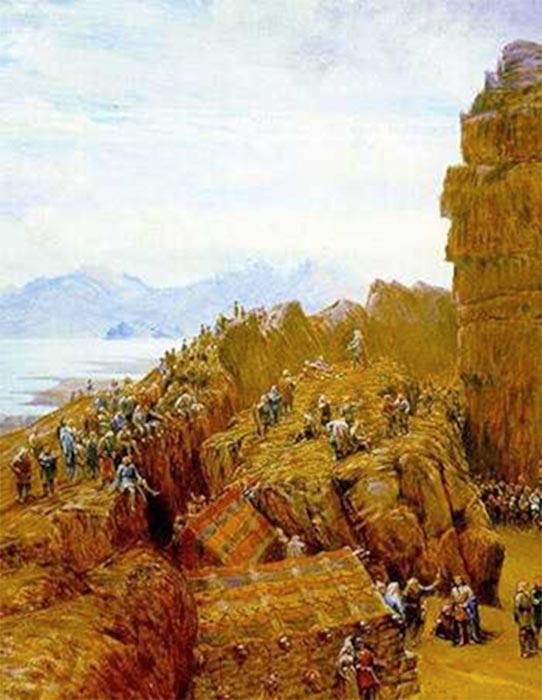

“Althing in Session.” 19th-century rendering of the Law Rock in Þingvellir by W. G. Collingwood (1854–1932) Bridgman Art Library (Public Domain)

Norse Things

According to Norway's Law of the Gulathing dating back to 900 - 1300 AD only ‘free men of full age’ could participate in Things, which functioned as both courts and parliaments administering local, regional, and supra-regional levels of Norse society. According to Natascha Mehler's 2015 paper “Þingvellir: A Place of Assembly and a Market?” they were judicial centers where disputes were resolved, political decisions were taken, and public religious rites associated with the election of chieftains and kings were conducted.

- The Ancient Parliamentary Plains of Iceland

- Storms In Scotland Unearth Viking Skeletons

- Vikings Used Sherwood Forest Long Before It Was Known as the Hideout of Robin Hood

In pre-Christian Germanic Scandinavia the most popular method of conflict resolution was feuding and Things managed potentially escalating tribal feuds to avoid social disorder, therefore, serving communities as forums for conflict resolution, negotiators of tribal alliances through marriage and settlers of inheritance disputes. All across Scandinavia Things were held at man-made ancestral burial mounds and at places with abundances of natural resources, for example at the Alþingi (Althing) national parliament of Iceland founded in 930 AD at Þingvellir (assembly fields) situated 45 kilometers (28 miles) east of the modern capital city, Reykjavík.

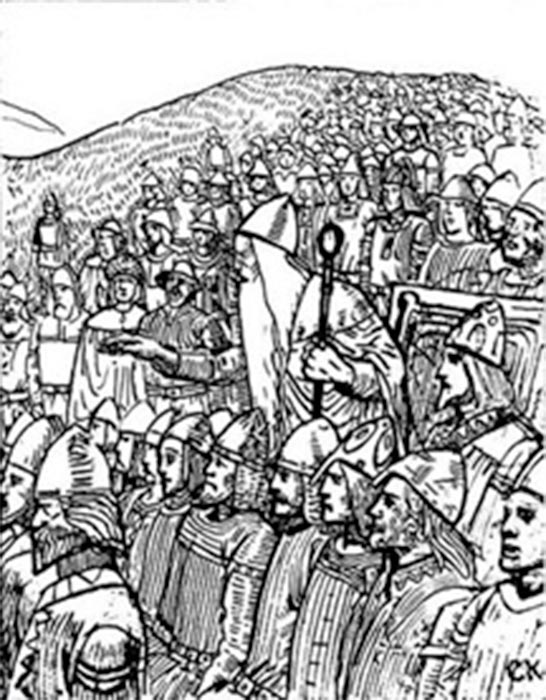

Christian Krohg: Illustration for Olav den helliges saga. Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker showing the power of his office to the King of Sweden at Gamla Uppsala, 1018. (Public Domain)

Ancient Norse Thing sites are often discovered near coastal and inland navigable water trade routes, and in Scandinavia they are often marked with large inscribed rune-stones, which according to archaeologists indicate specific families’ supremacy over local regions. Appointed ‘lawspeakers’ or early judges memorized, recited and legislated laws on behalf of local chieftains and kings and for this reason a growing number of historians point towards Things as the forerunners to modern democratic institutions. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, towards the end of the Viking Age, new state processes saw Norwegian kings consolidating their royal power and asserting new controls over their assemblies (Things,) as the traditional political and peace-keeping roles generated from these sacred site’s were ditched and they began functioning mainly as courts of law.

Viking Things in Foreign Territory

Things are not restricted to Viking Norway, Sweden, Iceland and Greenland. Since they played such a central function in the Germanic world they also featured across the British Isles. In England, Thingwall is a village on the Wirral Peninsula in North West England and Thynghowe was an important Danelaw meeting place, or Thing, located in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire, which archaeologists believe marks a boundary between the ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. This was recently confirmed when English Heritage discovered it was once called Thynghowe in a document dated to 1334 AD, with another text from 1609 AD saying it “resolved disputes and settled issues.” The second part of the name, the word howe, originates from the Old Norse word haugr meaning ‘mound’ which suggests Thynghowe was built upon a Neolithic burial mound dating to around 3000 BC.