The Ancient Celtic Thresholds Of Liminal Time And Space

The ‘Veil of Isis’ is an ancient metaphor and allegorical motif of mythology where nature is personified as the goddess Isis covered by a veil representing the mystery and inaccessibility of nature's infinite secrets. In mythology and religion liminal deities, like Isis, were gods or goddesses who presided over thresholds, gates, or doorways: the crossers of boundaries. While at the simplest level these deities could be called guardians of the passage to the underworld, in crossing the threshold between life and death the ancient cultures of Scotland and Ireland also worshiped a range of seasonal cyclical liminal deities. The crumbling ruins of Neolithic burial chambers and Bronze Age stone circles that encrust the Celtic landscape, deliver fragments of evidence at several archaeological sites, that collectively reveal just how textured the ancient world was with a range of conceptual veils.

Nature is personified by the goddess Artemis, and is revealing itself to a personified science, by Jan Luyken. Frontispiece to the book “Anatome Animalium" by Gerhard Blasius (1681) (Public Domain)

The Annual Veils Of Ancient Celtic Agriculture

October 31 is Halloween, or All Saint’s Day, which is a Christianized festival with Celtic origins. While pumpkins (originally turnips) are carved today by families wearing ghoulish costumes, back in pre-Christian days this date was Samhain (SAH-win). Nicholas Rogers’ 2002 book Samhain and the Celtic Origins of Halloween. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night explains that on this date the conceptual veil between this world and others was believed to be at its thinnest. While this fact relating to the date of Halloween is fairly widespread, what not so many people consider is that many of the standing stone monuments and massive stone built burial chambers of Scotland and Ireland were themselves ‘veils’ standing on the borders of liminal worlds, and dates.

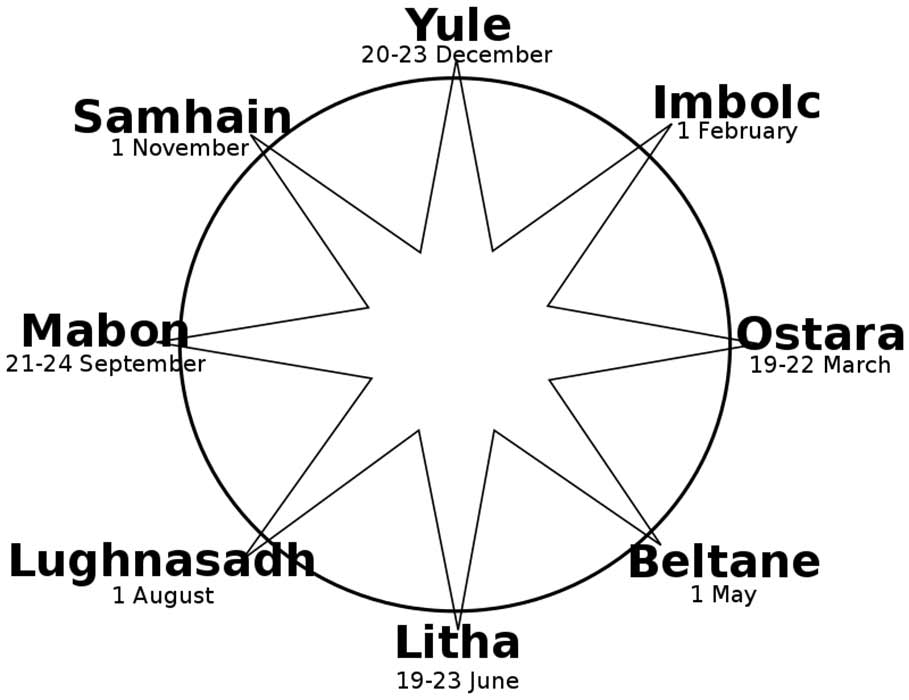

The Gaelic festival Samhain fell on October 31, beginning at sunset and continuing until sunset on November 1 (All Saint’s Day), approximately halfway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice. Thus, the date marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the winter, or ‘dark half’ of the year. Samhain was one of the four primary Celtic seasonal festivals, alongside Imbolc (February 1), Beltane (May 1) and Lughnasadh (August 1). Together these four sacred dates, with their cosmic origins, marked the four conceptual corners of the circular year. Why then, if Samhain occurred at harvest time was the festival associated with death, and the ‘veil’ between this world and the next being at its thinnest?

A plaster cast of an Irish Seán na Gealaí turnip lantern from the early 20th century at the Museum of Country Life. Ireland. ( Rannpháirtí anaithnid/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Beltane, that occurred six months earlier, on May 1, marked the time livestock were taken to their summer pastures to be fattened up before Samhain, when they were brought in from the fields to be slaughtered, hung and prepared for eating during the harsh winter months. Historian Eve Simpson Blantyre’s 1908 book, Folk Lore in Lowland Scotland, notes that during both the Beltane and Samhain festivals, marking the beginning of summer and winter respectively, great bonfires were lit on hill tops to signify the changing light patterns and to encourage the gods to provide protective and cleansing energies throughout the year. Because Samhain indicated the beginning of shorter days and longer nights, the bonfire in this festival was associated with the sun and the rituals were focused on fighting the forces of darkness.

The Wheel of the Celtic Year in the Northern Hemisphere. (Public Domain)