The Ancient Celtic Lords And Ladies Of Death

Traditionally, history classes have been focused on installing widespread knowledge of the ancient Greek gods of the Underworld, led by Hades, but less is taught about Nyx, the goddess of night, and even less again about her sons, Hypnos, the god of sleep, and his brother Thanatos, the personification of death itself. In Norse mythology, Hel was a child of the trickster god Loki and served mythology and religion as the goddess of death, however, the names of the gods and goddesses of death from the Celtic Underworld are much less known, perhaps because they less often feature in action movies like their Greek and Norse counterparts.

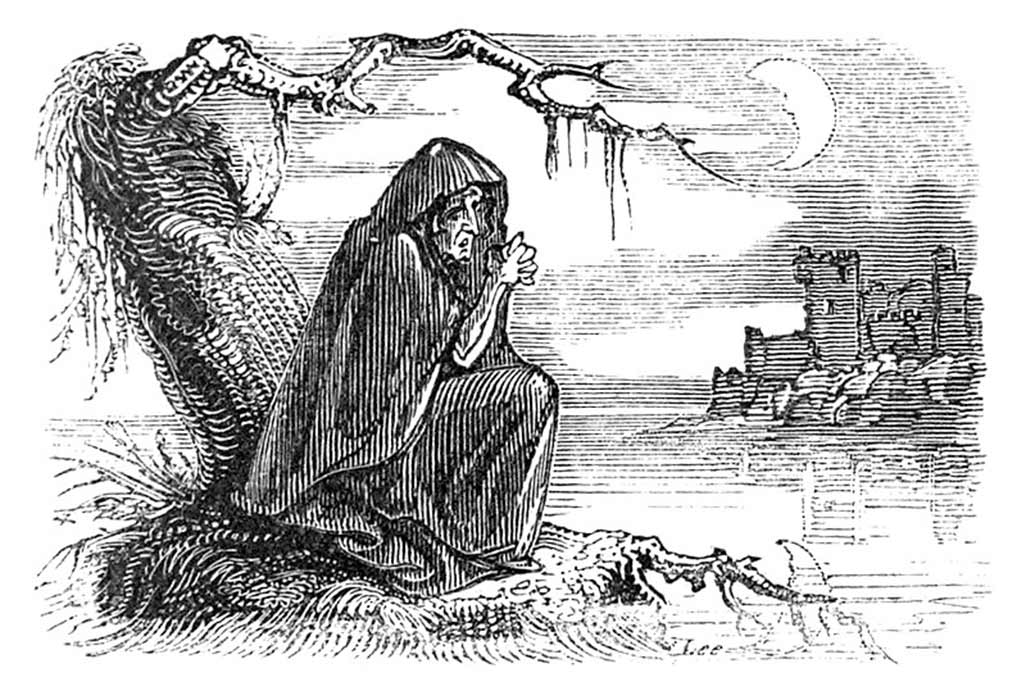

The Bunworth Banshee, as depicted in the 1825 book, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, by Thomas Crofton Croker, is a modern manifestation of the ancient Celtic deity, The Morrígan. (Public Domain)

The Otherworld Dwelling Of Deities

According to Biblical texts and early theologians, God's definitive judgment and entry to heaven is what early Christians expected upon death, with the fear of hell being promised to those who rejected God’s will through life. However, in Celtic mythology there was no ‘Afterlife’ as such, but an ‘Otherworld’ that was not only the realm of the dead, but also the dwelling place for a pantheon of ancient deities that interacted with humans in life and death.

John Duncan's "Riders of the Sidhe" (1911). In Irish mythology the Tuatha Dé Danann, were a supernatural race that represented the main deities of pre-Christian Gaelic Ireland. (Public Domain)

In Christianity, heaven and hell are taught to be actual places, most often causing both children and adults to struggle correlating this idea with the sky and the earth. This, however, was not an issue in old Celtic settlements across western Europe for the Afterlife was described as a parallel universe inhabited by all powerful deities. Celtic gods and goddesses were not believed to reside elsewhere, waiting for the departed souls to arrive after death, but they were perceived as often crossing back and forth to the human dimension, and Celtic heroes used magic to venture from here, into their realm.

Similarly to ancient Inca priests in what is today Peru - who also lived in an animistic reality where animals and natural forms were imbued with life force - administrators of Gallic cosmology perceived the universe as comprising three primary parts. Historian John T. Koch’s 2006 Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia explains: Albios (heaven, white-world, upper-world), Bitu (world of the living beings), and Dubnos (hell, lower-world, dark-world) and the Latin name Orbis alius, described the place souls go to before being reincarnated.

Oisín and Niamh approach ‘Tír na nÓg’ (the other land), which was one of the many names for the Celtic Otherworld. Illustration by Stephen Reid in T. W. Rolleston's ‘The High Deeds of Finn’ (1910). (Public Domain)