Perchance To Dream: Oneiromancy Ancient History Of Dream Interpretation

Dreams and their ancient interpretations are documented in contemporary written sources such as official inscriptions, literature, even special dream books, called oneirocritics, from Mesopotamia and Egypt's early civilizations. They demonstrate that dreams played an important role in government, religion and daily life. Despite the fact that early civilizations had a variety of ideas about what dreams were, they always seemed to place a high value on them. Dreams were regarded as an especially important gateway of receiving messages from the world of power and spirit, from the gods and other powerful beings. Dream interpretation was the responsibility of those with experience in such things in these groups such as tribal elders, matriarchs and patriarchs of the family or community, priests and shamans. Shamans were especially valued for their advice because they were able to enter the world of dreams at will through trances, encounter the souls of humans and other beings, fight, recover lost souls, heal, and bring the meaning of the dream forth to the life of the dreamers.

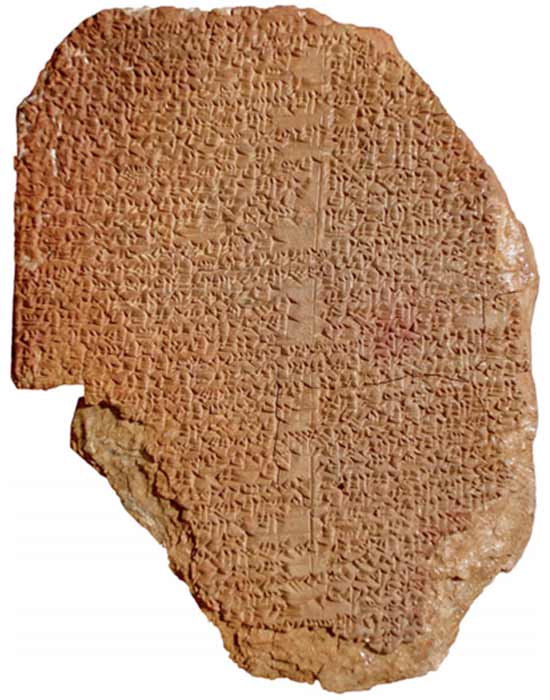

The Gilgamesh Dream Tablet, a 3600-year-old clay artifact originated in the area that is today Iraq (Public Domain)

Dreams Of Mesopotamian Kings

In the ancient Mesopotamian epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh (written c. 2100-1200 BC), the hero Gilgamesh has two dreams that foretell the arrival of his friend, Enkidu. Gilgamesh sees an axe fall from the sky in one of his dreams. He then notices people gathered around the axe in awe. Gilgamesh then throws the axe in front of his mother Ninsun and embraces the axe. Ninsun interprets the dream to mean that a powerful figure will appear soon. Gilgamesh will struggle with him and attempt to overpower him, but he will fail and they will eventually become close friends and achieve great things together. Later in the epic, Enkidu also dreams about the heroes' encounter with the giant Humbaba. Tablet VII of the epic describes Enkidu telling Gilgamesh of a dream in which he saw the gods Anu (the Sky Father), Enlil (the god of wind, earth and storms), and Shamash (the god of truth and justice) condemn him to death. In addition, he has a dream in which he travels to the Underworld.

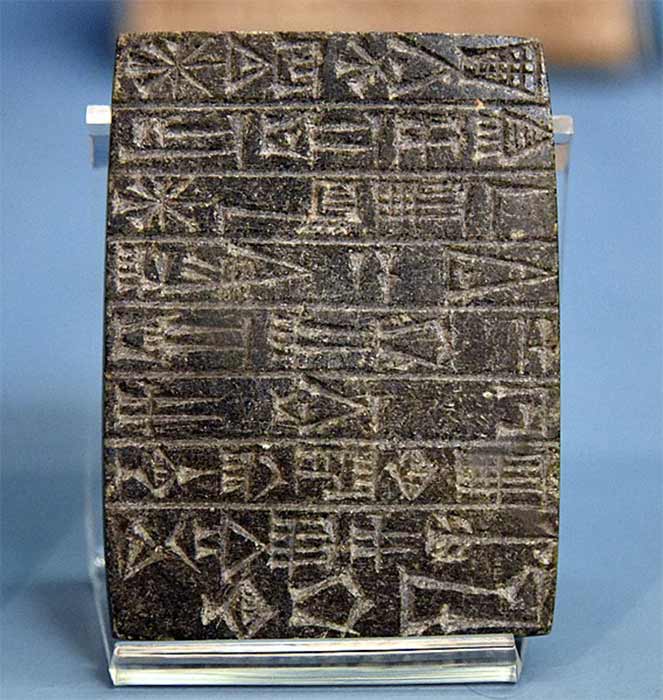

Votive inscription of Gudea, ruler of Lagash mentioning the construction of the temple of E-ninnu for the god Ningirsu. From Lagash, Iraq. (22nd century BC) Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Gudea, king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash (reigned c. 2144 – 2124 BC), recorded his own dream on a clay cylinder, which still exists to this day. The priestess Nanshe interpreted the dream of several monstrous figures as a command to Gudea to build a temple for the god Ningirsu. Later, the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883 – 859 BC) constructed a temple to Mamu, the Assyrian god of dreams, near Kalhu at the ancient Assyrian city of Imgur-Enlil. Several generations later his namesake, king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668 – c. 627 BC) had a dream in which the goddess Ishtar, the goddess of war and love, as well as his divine patroness, appeared to him and promised to lead him to victory in an impeding battle. Ikar Zaqqu, a surviving collection of dream omens, records various dream scenarios as well as possible outcomes for the person who experiences each dream, based on previous cases.

- Oneiromancy: Dream Predictions in Ancient Mesopotamia

- Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Greece

- The Egyptian Dream Book

Although the successful dream interpreters in Gilgamesh, as in most Mesopotamian literature, were always women, professional dream interpreters existed in all ancient civilizations and in practice they were both men and women. In ancient Babylonia, dream interpreter-priests or ‘seers’ called baru (to unfold, explicate, set at ease) had the ability to tell the meaning of dreams and take actions to avoid their potentially negative consequences. This function was necessary because there were a number of gods were associated with dreams in Mesopotamia, and not all of them were kind. They included the Sumerian Mamu (the god of dreams), the Babylonian Makhir, the favorable goddess of dreams, and the Akkadian Zaqu or Zaqiqu, a nocturnal demon capable of causing nightmares.

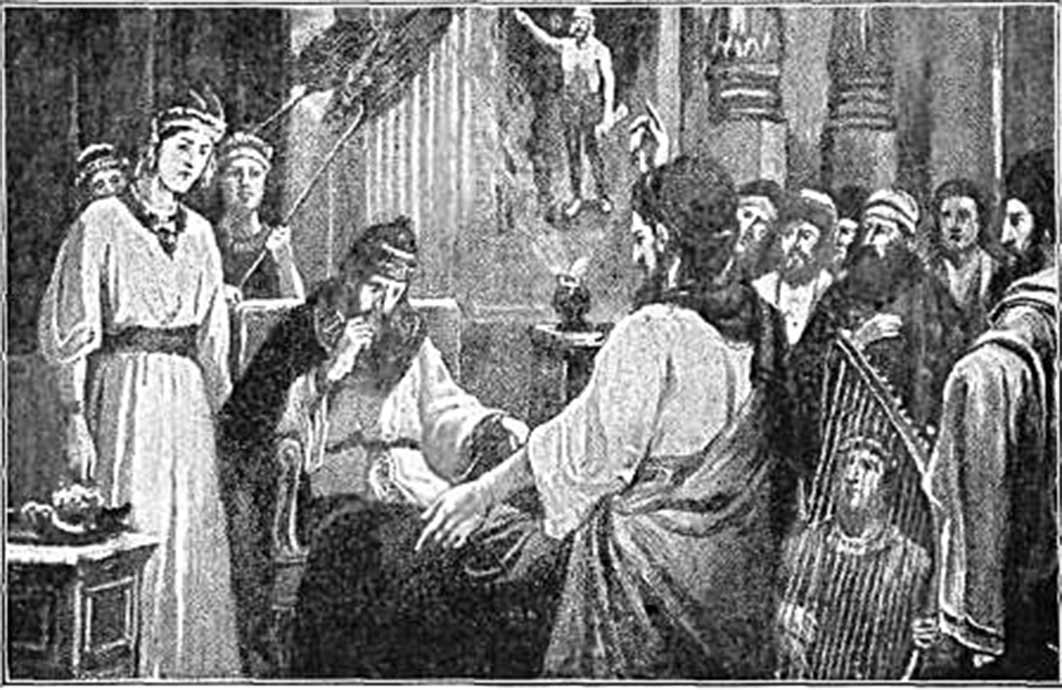

Daniel interprets Nebuchadnezzar's Dream by W. A. Spicer (1917) (Public Domain)