The Truth behind Christian Miraculous Preservation: How Mummies Become Incorruptible Saints

The Roman Catholic Church has given the title “saint” to thousands of real and legendary people, and even to some non-human entities, such as St. Michael the Archangel. The most comprehensive listing of saints is the Bibliotheca Sanctorum, which has eighteen volumes and lists more than 10,000 saints. However, there are many more than this in the Roman Catholic tradition; most of their names are now lost. And although the term initially referenced all baptized believers (hagioi in Greek), in modern times sainthood is an elaborate and expensive process, sometimes costing more than $500,000 in fees before the Church will grant someone such a status. This is how a saint is made:

An old canonical law stated that a potential candidate for sainthood must have been dead more than 50 years before the cause could begin, and although that is no longer official, it is rare for a cause to open for someone who has been dead for less time. People therefore initiate causes long after candidates’ deaths. When an individual or group wants someone named a saint, they begin raising money and publishing the candidate’s biographical accounts. Once enough promotion occurs, they ask a local bishop to begin the formal procedure. Called the Ordinary Process, adherents refer to the candidate as a “Servant of God” at this stage. First, all the potential candidate’s writings and teachings are examined for orthodoxy; if anything is found that counters the Roman Catholic Church’s statements − if the individual had a different opinion on some matters for example − the process cannot move forward. If there are no conflicts, the local bishop creates a tribunal, and witnesses for and against the candidate’s sanctity come to testify. During this process, the bishop must be sure that the individual is not the object of worship. As long as this is not the case and significant evidence for his or her holiness exists, the next phase in Rome begins. A canonical lawyer (trained and licensed by the Vatican) is hired, who presents gathered evidence to congregational judges.

The saint-making process is to promulgate the faith and to curb unsanctioned cults. Photograph © Ken Jeremiah

Then, others take the role of Devil’s Advocate and write objections to the lawyer’s brief. He responds in writing, and then the process repeats. Sometimes, this exchange takes years. Once all opinions have been shared and an agreement reached, the cause moves forward and a positio is prepared: this is an extremely lengthy document (often more than 1,000 pages), which costs $13,000 for 100 copies (Woodward, 1996). Tipografia Guerra does all the Vatican’s printing, and despite the amazing cost, the Church requires the use of this company, as it is one of its partner corporations. One hundred copies of the positio are necessary because all cardinals, official prelates, and others involved in the process read it. If they reach an agreement that the cause should continue, they send a notification to the pope, and if he also agrees, he announces the cause’s official introduction, at which time the lawyer prepares another document called informatio, which provides information about the virtues and holiness of the candidate, who at this point the faithful can call a venerable.

- Dying to Live Forever: The Reasons behind Self-Mummification

- The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo

- Ten Incredible Mummy Discoveries from Around the World

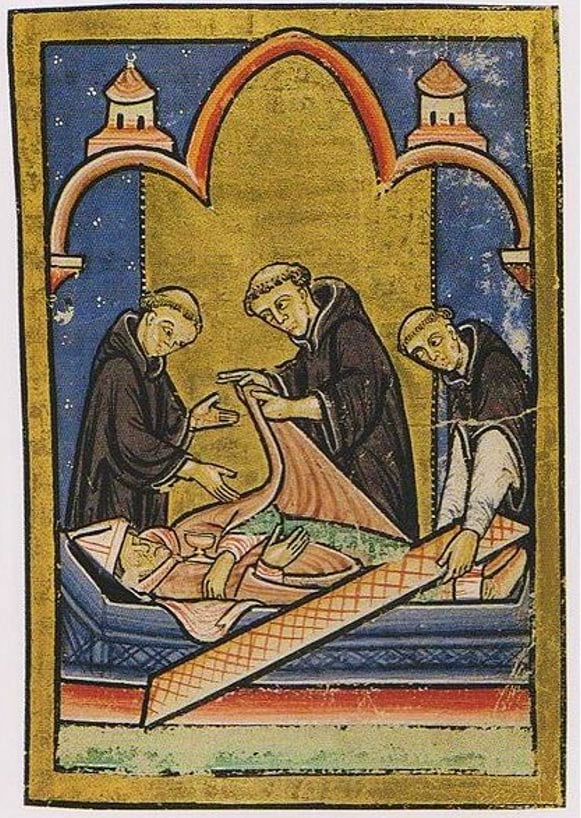

Clergy members exhume and examine his or her body, and in the past, if they found that the body was preserved, they considered it a miracle and the cause gained a momentous boost forward. This was because a certain number of miracles were required for beatification (in which the Church allows its adherents to venerate the individual locally) and canonization (in which the Vatican allows his or her veneration by anyone worldwide). Each miracle needs an investigation, which also requires positiones that cost $4,000 each to print. Eventually, provided the miracles received confirmation, the candidate attained the title beatus (the male term) or beata (the feminine designation). At this point, the cause ended. It did not begin again until two more miracles occurred that the Church attributed to the Blessed. Even in modern times, this is the case. Once such miracles occur, they are both investigated and more positiones are written and printed, and provided they are judged actual miracles, the individual is named a Saint.

A miniature depicting the miracle where Cuthbert's body is discovered incorrupt. Public Domain

Believers think that saints’ bodies contain divine energy, and centuries ago, they slept in tombs or catacombs that contained saintly remains. They believed that the soul was composed of multiple aspects, (an idea adopted from the Egyptian faith, like many other concepts in Christianity), and while part of the saint’s soul was in heaven, the other part was with his or her earthly remains. For the same reason, people thought that the closer someone was buried to a saint, the easier it would be for him or her to enter heaven. Even today, belief in the miraculous capabilities of saints’ corpses has not waned, and bodies are in and around just about every church and cathedral in Europe. In Italy alone more than 300 bodies or body parts are displayed at Catholic sites. Many of them are said to have been miraculously preserved.