The Problem With Labelling Alexander, The Macedonian King With A Mercurial Character

‘It is a naive belief that the distant past can be recovered from written texts, but even the written evidence for Alexander is scarce and often peculiar,’ says Robin Lane Fox in Alexander the Great (2004). Over the centuries, historians have expressed, in one way or another, the uncomfortable relationship between what they deem likely to have happened and what is claimed to have come to pass. In the modern age, this conundrum has sparked a whole industry analyzing our library of written historical sources.

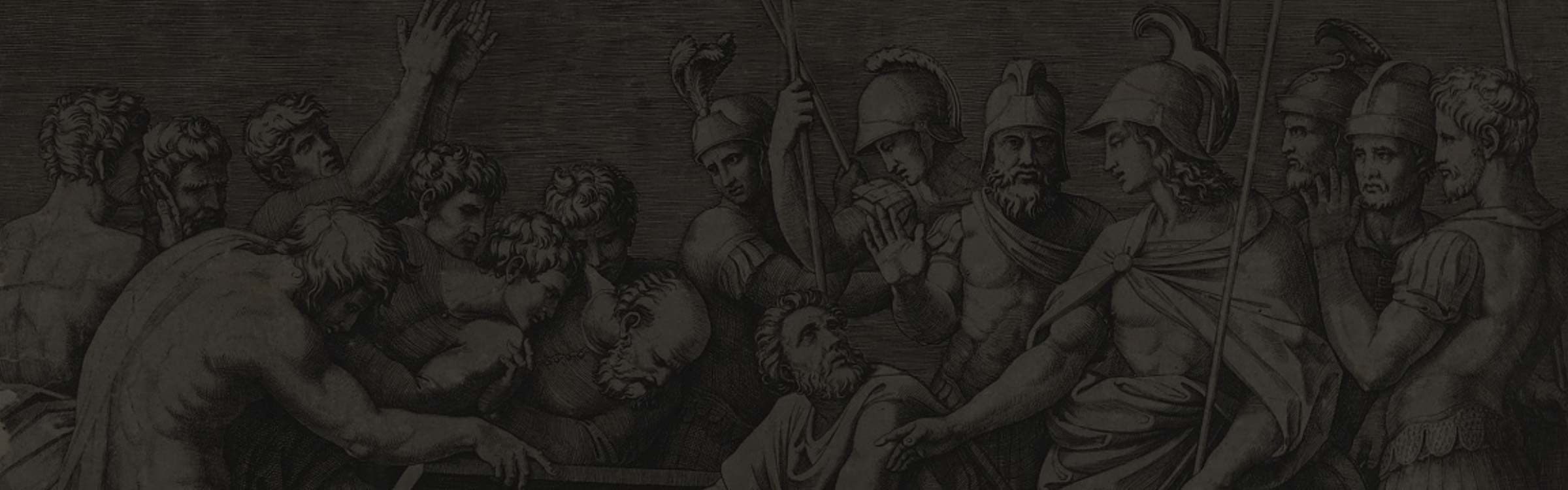

Mosaic Alexander the Great and Craterus in a lion hunt (late fourth century BC) Pella Archaeologic Museum (Public Domain)

Alexander The Great Alchemist Of History

In ancient Greece, however, from the dawn of the oral tradition which gave us the names of gods and heroes, down to the legendary deeds of mortals which gradually emerged from the rubble of Dark Age Greece along with a new alphabet, the convention of campfire listeners entranced by a travelling bard was to swallow this ‘myth-history’ whole, or risk committing impiety. In the case of the royal clan of ancient Macedon – the Temenids or Argeads, as they are alternatively known (depending upon which founding myth they are linked to) – there lies an additional challenge: the nation’s warlord kings willingly fused this paradox together. And there was no greater alchemist of history than Alexander the Great.

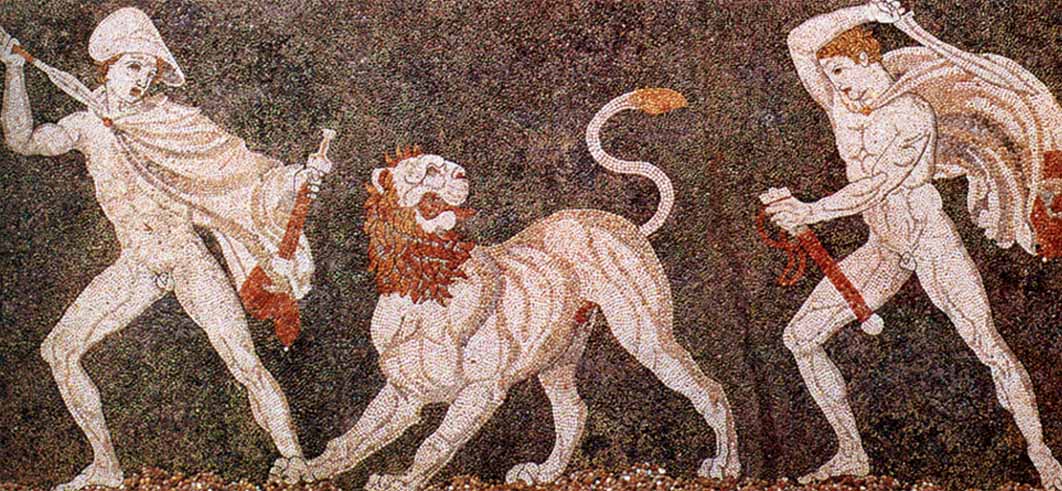

Alexander the Great commanding that the work of Homer be placed in the tomb of Achilles by Marcantonio Raimondi (ca. 1500–1534) Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

Alexander’s lineage was the perfect storm for not just sweeping aside the status quo (his father had already seen to that), but for bridging the growing divide between an ever-more rationalized present (largely thanks to his tutor, Aristotle) and the mythopoeic past (thanks to the epics of Homer). Alexander made sure that his story would forever be more enduring than a mortal lifespan, and less challengeable than fact, and his brilliantly talented entourage had everything to gain from this new apotheosis.

The Ancient Sources

Today, historians are faced with the unique task of unravelling the many faces of the campaigning king: the sensitive adolescent, the ruthless warlord, the classically educated monarch and the oriental Great King-cum-Pharaoh whose legend metamorphosed into romance in the chaos of the Hellenistic world he fathered. Consequently, the age-old question remains: how do we divide Alexander’s biographical pie into the correctly characterized proportions? The answer lies in the ancient sources: that knotted and frayed ball of historically intertwined string.

Interest in the emotional language and source fidelity of the life and times of Alexander was rekindled in the Renaissance when already-ancient manuscripts, discovered lying in damp scriptoriums where they had been forgotten for centuries or ferried West in haste away from the Ottoman threat, were mined for wisdoms of old. But this process of enlightenment, unfortunately, saw a proliferation of new deceits. Since then, and sped along by new forensic techniques in historiography developed over the last two centuries, classical scholars – and philologists in particular – have dedicated themselves to separating the ‘historical’ out of the total written evidence contained in classical literature. The quest has solicited contemplations from some of the greatest minds of the ages: the philosophers, priests, politicians, antiquarians and polymaths attempting to unlock the gates of the past. Many concluded that duplicity of one kind or another, subtle or overt, is endemic to the narrating of ‘history’, so that falsifications and the forensic method to unravel them competed on every page. A most fertile weapons testing ground remains the life of Alexander.

- Alexander the Great: The Economics of Upheaval

- The Last Will and Testament of Alexander the Great: Its Appearance, Disappearance And Legacy

- Was Alexander the Great Entombed In Venice In Disguise As St Mark?

No modern scholar could complain that we had not been provided with fair warning. Two thousand years ago, the Roman geographer Strabo (ca. 64 BC–AD 24) voiced his concern by writing that ‘all who wrote about Alexander preferred the marvellous to the true’. Even the Stoic soldier-historian Arrian (ca. 86–160 AD), a great Alexander admirer who used ‘court sources’ to obtain ‘reliable’ detail, could not help but voice his frustration: ‘no one else has been the subject of so many writers with such discrepancy between them.’ He therefore attempted to set the record straight, as he saw it anyway, or wished it to be seen.