Measuring Up The Mega And Mini-Henges Of Neolithic Britain

The dictionary description of a ‘henge’ as “a circular area, often containing a circle of stones or sometimes wooden posts, dating from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages,” fails to depart that these circular or oval earthen enclosures dating from around 3000 BC to 2000 BC - the Neolithic or ‘new Stone Age and early Bronze Age - represent sacred spaces that served ancient British communities’ spiritual needs in the way modern churches, mosques and synagogues do today.

Essentially a ‘henge’ is a ditch that forms a sacred space with a defined center where order prevails, as opposed to the wild and unpredictable surrounding-outside world. Every henge is formed by a circular-shaped outer bank with an entry causeway crossing internal ditches, and many have multiple rings of this bank-and-ditch design. While countless thousands of these structures once peppered Neolithic Britain and Ireland, less than 100 survive today. According to Jim Leary in his 2016-paper Valley of the henges, contrary to most Neolithic sacred sites, which are often perched on the shoulders of hills, henge structures are mostly found on low-lying agricultural land beside rivers, such as the Maelmin Henge reconstruction in England’s Northumberland which features the so-called Milfield North Henge monument, located in a low-lying Neolithic agricultural zone.

The Maelmin Henge was reconstructed in 2000 using only the tools available to people 5,000 years ago. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Hidden Sacred Purpose Of Henges

In Britain, henges usually measure greater than 20 meters (66 feet) in diameter. When they were first identified in the early 19th century it was considered that they were defensive in nature, but because they feature internal ditches located behind outer banks, which is an awful defensive format, it is now generally accepted they were used for rituals and cult worship. This idea is supported in that most henges contain inner grottoes, timber and stone circles, and otherworldly artifacts are often recovered amidst deliberately smashed pottery at the center. A good example of ritual goings on within Neolithic henge monuments is to be found at Cairnpapple Hill, situated about three kilometers (two miles) north of Bathgate in southern central Scotland. At this site, not only was evidence of earlier cremations found, but also the deliberate smashing of pottery that predated the building of the henge enclosure. This means the actual location was already a traditional sacred site and that later users exemplified and immortalized it by digging a henge and building a huge stone burial cairn.

Aerial photo of the remains of the 4,000-year-old henge and cairn burial enclosure at Cairnpapple Hill. (Dr John Wells / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Marden Henge And Wilsford Henge

Britain’s top three largest stone circles, all of which are surrounded by henges, would certainly include Avebury, the Great Circle at Stanton Drew stone circles and the Ring of Brodgar in Orkney, but according to James Dyre’s 2001-book Discovering Prehistoric England the most voluminous henge ever discovered in Britain is Marden Henge, also known as Hatfield Earthworks, located north-east of the village of Marden, Wiltshire, England.

- The Sacred Prehistoric Neolithic Complex of the Thornborough Henges

- Are There Hidden Depths to the Golden Lozenge of Stonehenge?

- Forsaken by their Gods, Four Ruins of the Oldest Temples in the World

The site was first identified in 1953 and it was excavated in 1969, at which time the north entrance was discovered. Inside this sacred enclosure Neolithic people had built a vast timber circle, and similarly to Cairnpapple in Scotland, they smashed grooved ware pottery, ritually. Between 2010-2018 the Department of Archaeology at the University of Reading conducted aerial and geophysical surveys at this site revealing the true dimensions of this ancient megastructure.

North side of the Marden Henge site, looking west, showing part of the outer earthwork bank. (CC0)

Covering four hectares (35 acres) at its greatest width, this loosely oval-shaped banked enclosure measures 530 meters (1738 feet) in circumference. An internal ditch has been cut in the east, north and north-west sides, and also on the southern and western aspects beside the River Avon. Again like Cairnpapple in Scotland, at the center of Marden Henge there were originally standing stones and a huge internal mound called the Hatfield Barrow, but this collapsed after it was excavated in the 19th century and ploughing by modern tractors has destroyed the last of the stone menhirs. It would be erroneous to interpret this site as a stand-alone ancient feature in the landscape because it is part of a complex of similar henges. A short distance from Marden Henge another enclosed sacred site is found, called Wilsford Henge, to the west of the village of Wilsford, within the Vale of Pewsey. In 2015 archaeologists from the University of Reading discovered an early Bronze Age child buried in a crouched position surrounded with smashed potters and a collection of necklace beads.

Funerary Hoard Of Bush Barrow Henge

In 1808 at Bush Barrow Henge, situated around one kilometer (.62 miles) south-west of Stonehenge on Normanton Down, archaeologists William Cunnington and Sir Richard Colt Hoare not only discovered a male skeleton but also a collection of funerary goods that made it 'the richest and most significant example of a Bronze Age burial monument not only in the Normanton Group or in association with Stonehenge, but arguably in the whole of Britain”. The most outstanding pieces dating from the Bronze Age include a large 'lozenge'-shaped sheet of gold, a sheet gold belt plate, three bronze daggers, a bronze axe, a stone macehead and bronze rivets, all on display at the Wiltshire Museum.

Larger gold lozenge with gold belt buckle and a copper dagger recovered from Bush Barrow, on display at the Wiltshire Museum.(CC0)

The 2010-Stonehenge World Heritage Site – Landscape Project: Normanton Down: Archaeological Survey Report describes this henge site as a broad irregular penannular ring ditch with an internal diameter of 43 meters (141 feet) and an external diameter of between 58 meters (190 feet) and 65 meters (213). The broad and very irregular ditch (henge) measures between five meters (16.4 feet) and 14 meters (45.93 feet) wide. An entrance causeway was aligned to face the River Avon the north-east which measures 12 meters (39.37 feet) wide, and eight pits face this opening in the enclosure. A series of further pits are located at distances of 20 meters (65.61 feet) and 70 meters (229.65 feet) to the south-west of the enclosure, but it is argued that these are not ritualistic features, but natural depressions in the field.

Aligned north to south, these are the three great henges of the Thornborough Henges complex. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Thornborough Henge Complex

Close to the town of Masham in North Yorkshire, England, often called 'The Stonehenge of the North' - Thornborough Henges is the name given to a collection of ancient structures dating from between 3500 and 2500 BC including, alongside the three henges, a cursus ditch monument, burial grounds and living settlements. Representing the oldest ritual structure at this site is an east/west aligned cursus (ritual embankment) that measures around 1.6 kilometers (one mile) running from Thornborough village to the River Ure. Constructed by two deep parallel ditches, a series of burial mounds and enclosures have been found alongside this cursus monument suggesting it had ceremonial functionality long before the creation of stone cairns in the late Neolithic period.

Durrington Walls Neolithic Settlement

While the henges at Thornborough are impressive they fall far short of Britain’s “super-henge” category, which does include Durrington Walls Neolithic settlement and later henge enclosure, located just north of Amesbury, Wiltshire, in the Stonehenge World Heritage Site. In 2006 archaeologists from the University of Sheffield excavated seven houses dating to around 2600 BC, from the original 1,000 homes that are suspected to have housed as many as 4,000 people, and this is why the site is regarded as a complementary monument to Stonehenge. In 2020 a geophysical survey uncovered 10 meter (33 feet) deep pits that are suspected to have held massive timbers forming a 1.9 kilometer (1.2 mile) wide circle, which if correct, makes this Britain's largest prehistoric monument.

The southern wall of Durrington Walls prehistoric site.( Ethan Doyle White /CC BY-SA 4.0)

The henge at Durrington Walls was constructed on high ground sloping to the south-east towards a bend in the River Avon, which is located only 60 meters (200 feet) distant from the site. While the structure has greatly eroded, visitors can still see the inner slope of the bank and the outer slope of the internal ditch. According to Julian Thomas’ 2011-paper Reconsidering Ritual at Durrington Walls the bank was originally, in some areas, 30 meters (98 feet) wide and the ditch measures five-and-a half meters (18 feet) deep, seven meters (23 feet) wide at its bottom and 18 meters (59 feet) wide at the top. Within the enclosure several timber circles and smaller enclosures have been discovered which were accessed through two entrances cut into the bank and ditch at the north-western and south-eastern ends of the henge. It is suspected that there were two further entrances onto the sacred space in the north-east and to the south.

Sunrise at the Durrington Walls reconstruction, which was produced for a special episode of Time Team that first aired in 2005. (Karen Krik / Fair use)

Mount Pleasant Neolithic Structure

Another site in the mega-henge category is the Mount Pleasant Neolithic structure located near Dorchester, where the Rivers Frome and South Winterborne form a distinct V-shape. Unlike Britain’s other mega-henges: Marden and Avebury, which are located in low-lying valleys and glens, the highest point of this one is located on the Alington Ridge overlooking a crossing on the River Frome. The multiple Neolithic monuments at this site are dominated by the huge oval-shaped henge enclosure measuring around 370 meters (1,213 feet) east to west and 320 meters (1049 feet) north to south. The outer bank originally measured four meters (13.12) tall and between 16 meters (52.49 feet) and 23 meters (75.45 feet) wide, and the inner ditch ranges in width from nine meters to 17 meters wide. Recent dating projects at this site suggest the separate ritual elements were brought together here much quicker than previously calculated.

A Current Archaeology article informs that in the 1970s archaeologist Geoff Wainwright documented not only the henge but also “a tall wooden palisade, a huge round mound, and a mysterious structure formed from concentric arrangements of timber and stone.” Furthermore, Wainwright’s 1970s archive of artifacts from this site, which is stored at Dorset County Museum, included charcoal, fragments of human bone and antler picks used to dig out the henge. In 2020 Professor Susan Greaney from Cardiff University published a paper titled Tempo of a Mega-henge: A New Chronology for Mount Pleasant, in the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, suggesting this site has not evolved over a millennia, like at most other sites in Britain, but in little more than a century. The antler picks and charcoal samples taken from the surrounding ditch and beneath the enclosure suggest this henge was first created around 2555 - 2400 BC. Greaney concluded that the entire process of constructing Mount Pleasant, from the formation of the henge enclosure to the digging of the ditch around Site IV, “took no more than 35-125 years: a radically shorter period than has been suggested before”.

Mount Pleasant Henge, just outside of Dorchester, Dorset, is a heavily-eroded Neolithic henge visible as a white crop-mark in this photograph taken in the spring. (CC BY-SA 1.0)

Flagstones Henge And The Druid Stone

Also located in Dorchester, only 500 meters (1,640 feet) east of Mount Pleasant Henge, is the Flagstones late Neolithic ditch that was discovered in 1891 when workmen were digging under the lawn at Thomas Hardy's house at Max Gate. The first indicator that a Neolithic site had once occupied this site was the discovery of a huge stone, the so-called Druid Stone (now sarsen stone), that was buried about three feet ( one meter) underground.

The so-called "Druid Stone" from the Neolithic Flagstones Enclosure, found at Thomas Hardy's house in 1891. (CC0)

Estimated to be around 100 meters (328 feet) in diameter at least half of the Flagstones Henge enclosure, which comprises a circular ring of unevenly spaced pits dug into the chalk bedrock, was excavated in 1987-8 and the other half is still beneath the grounds of Max Gate. Archaeologists discovered an adult cremation and two child burials at the bottom of the ditch beneath sandstone slabs that determined the site was functional between 3486–2886 BC. Furthermore, evidence was found to suggest this site was associated with the nearby Mount Pleasant Henge and Maumbury Rings.

Hindwell Roman Fort Site

Skipping over the English border with Wales, the Neolithic palisaded enclosure to the east of the Hindwell Roman Fort is a loosely oval-shaped enclosure that was constructed around 2700 BC. Measuring about 880 meters (2,887 feet) east to west, by 540 meters (1,771 feet) north to south, this site in clearer visual terms equates to around the size of 55 modern football pitches. Like most other henge enclosures, so too is this one defined by a ring of pits that once held huge timbers measuring two meters (6.56 feet) across and the same in depth. While many of Britain’s henge structures have multiple entrance causeways, this one features only a single narrow entrance at the western end flanked by comparatively huge six meter (19.68 feet) diameter pits.

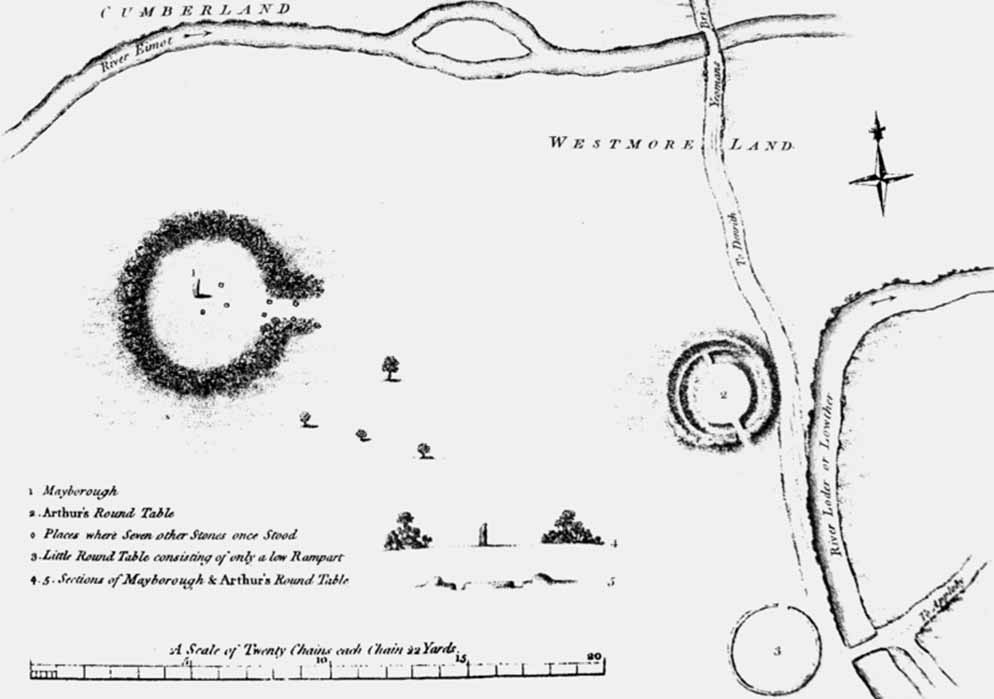

Mayburgh Henge And King Artur’s Round Table

Returning to England, in the county of Cumbria, Mayburgh Henge and King Arthur's Round Table Henge are located beside the village of Eamont Bridge, about two kilometers (one mile) south-east of Penrith. Beginning with Mayburgh Henge, the bank measures around six-and-a-half meters (15 feet) high, around 50 meters (164 feet) across the base and it has a diameter of around 117 meters (383 feet). According to archaeologist David Barrowclough in his 2010 book Prehistoric Cumbria, Mayburgh Henge is a single circular bank that was built using as a many as 20,000 cobble stones collected from the river, which makes it unlike most other henge monuments where the earth dug out from the ditches was piled up to form the surrounding banks. However, other archaeologists argue that the site was built upon Ice Age scree (build up of rocks), which accounts for the estimated 20,000 stones trapped within the matrix of the earthen bank.

Panorama of the Mayburgh Henge showing large circular bank and the center stone ( Dougsim - /CC BY-SA 4.0)

Located in a field next to the A6 road in the village of Eamont Bridge, south of Penrith, Cumbria, only 400 meters (1312 feet) to the east of Mayburgh henge, is King Arthur's Round Table Henge. Measuring around 90 meters (295 feet) in diameter this ditch extends up to 16 meters (52.49 feet) wide with the bank being about 13 meters (42.65 feet) wide. Compared with most of the henges featured in this article, King Arthur's Round Table Henge was measured as early as 1664 when English Antiquarian William Dugdale sketched two opposing entrances. The entrance to the south-east can still be seen today but the second one, in the north-west, is now buried beneath the A6 road. In the 1930s archaeologists revealed that the ditch had been cleared out and reshaped and they identified a cremation trench near the center of the henge.

Plan and sections of Mayburgh Henge and King Arthur's Round Table prehistoric monuments, near Penrith, Cumbria (1769) (Public Domain)

While many of Britain’s Neolithic henges are identified by their enormity as mega-henges, size was not everything when it came to worshipping deities in the Neolithic period. A 2015 article in The Times titled Stone Me! Britain is full of mini henges featured the story of the discovery of over 100 mini-henges on Exmoor, in west Somerset and north Devon in south-west England. Describing the sites collectively as “miniature versions of Stonehenge,” Professor Mark Gillings, an archaeologist at Leicester University, told The Times that most of these so-called mini-henges “were below knee height, so small that archaeologists had simply not noticed them until now”. Gillings says: “We all focus on the giant megalithic structures” but he pointed out that “they were just the biggest,” alluding to the presence of greater complexity at other, smaller sites. The researcher said Neolithic people were doing the same thing on a small scale all over the place, digging tiny ditches and erecting extremely small standing stones in circles, lines and other shapes.

Given this recent discovery of hundreds of mini-henges across Britain, one might consider to how many thousands of similar smaller Neolithic structures have been ploughed away, and remain hidden beneath modern farm buildings, villages, towns and city suburbs. But more so, having learned about the sacredness of ditches, one must question why the period around 3,000 BC is so often called the Neolithic (New Stone Age), when the ‘Henge-Age’, is a much more apt term, for there were countless more ditches dug than there were stones raised, at that early time.

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. www.ashleycowie.com.

Top Image: Remains of Knowlton church and henge (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By: Ashley Cowie

References

Barrett, K. and Bowden, M. 2010. Stonehenge World Heritage Site – Landscape Project: Normanton Down: Archaeological Survey Report. Research Department Report Series. Vol. 90–2010. English Heritage

Barrowclough, D. 2010. Prehistoric Cumbria. Stroud: The History Press.

BBC News. 19 July 2010. Marden Henge dig uncovers 4,500-year-old dwelling. Read online here. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-wiltshire-10684042

Bersu, G. 1940. King Arthur's Round Table. Final report, including the excavations of 1939, with an appendix on the Little Round Table. Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, 40.

Current Archaeology. 2021. Rise of the Mega-Henges. Current Archaeology. Read online here. https://archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/rise-of-the-mega-henges.htm

Dyer, J. 2001. Discovering Prehistoric England (2nd ed.). Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Greaney, S., Hazell, Z., Barclay, A., Ramsey, C., Dunbar, E., Hajdas, I., . . . Marshall, P. 2020. Tempo of a Mega-henge: A New Chronology for Mount Pleasant, Dorchester, Dorset. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 86. doi:10.1017/ppr.2020.6. Read online here: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-prehistoric-society/article/abs/tempo-of-a-megahenge-a-new-chronology-for-mount-pleasant-dorchester-dorset/5BBBD5F94960F9FA3C3A876705B8EA86

Feachem, R. 1977. Guide to Prehistoric Scotland. R B.T.Batsford Ltd.

Flagstones Enclosure. Megalithic Portal. Read online here. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=7772

Hammond, N. 2004. Battle to preserve Thornborough henges. The Times. Read online here. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/battle-to-preserve-thornborough-henges-93s3062lkhc.

Hardy, T. and Hardy, F. 2007. The Life of Thomas Hardy. Wordsworth.

Historic England. "Flagstones Enclosure (983955). Research records (formerly PastScape). Read online here https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=983955&resourceID=19191

Jonathan, L. 2015. Stone Me! Britain is full of mini henges. The Times

Leach, S. 2019. King Arthur's Round Table Revisited: A Review Of Two Rival Interpretations Of A Henge Monument Near Penrith, In Cumbria. The Antiquaries Journal, 99

Leary, J.; Clarke, A. and Bell, M. 2016. Valley of the henges. Current Archaeology. XXVII, No. 4 (316):

Malone, C. 2001. Neolithic Britain and Ireland. The History press.

Millet, T. 2015 Archaeologists unearth a skeleton in a Bronze Age burial at the Wilsford Henge excavation near Marden. Marlborough News. Read online here. http://www.marlboroughnewsonline.co.uk/news/all-the-news/4550-archaeologists-unearth-a-skeleton-in-a-bronze-age-burial-at-the-wilsford-henge-excavation-near-marden

Noble, W.J. 2007. Traces of Ancient Village Found Near Stonehenge. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/30/science/30cnd-stonehenge.html.

Thomas, J. 2011. Reconsidering Ritual at Durrington Walls. In Insoll, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford University Press.

The Walton Basin: Survey at the Hindwell Neolithic Enclosure' 1999 CPAT.

UNESCO World Heritage. Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Read online here. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/373/