Six Sexy Semi-Divine Superfoods Of Ancient South America

One need not search too long ago into South American history to identify a range of consumable drinks that would challenge and defeat, hands down, any of their modern derivatives - which are mostly fads fluttering in and out of culinary fashion, depending on their marketeers. The term “superfood” in a marketing context of green and brown packaged products, often with leaf designs, offer greater-than-normal nutrient density and a range of health benefits for what amounts to often three times the cost of non-superfoods. Ten years ago, the scientific opinion was split, but nowadays the vast majority of nutritional scientists greatly dispute the alleged health benefits touted by food giants and their alleged superfoods. However, this was not the case of authentic Mesoamerican superfoods.

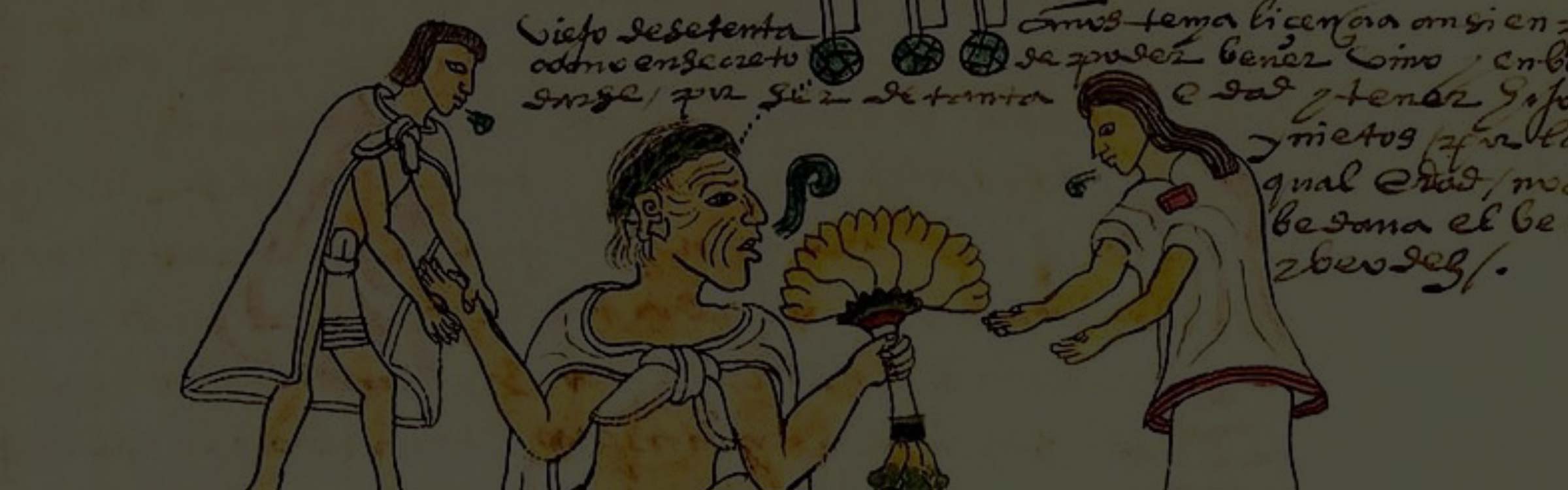

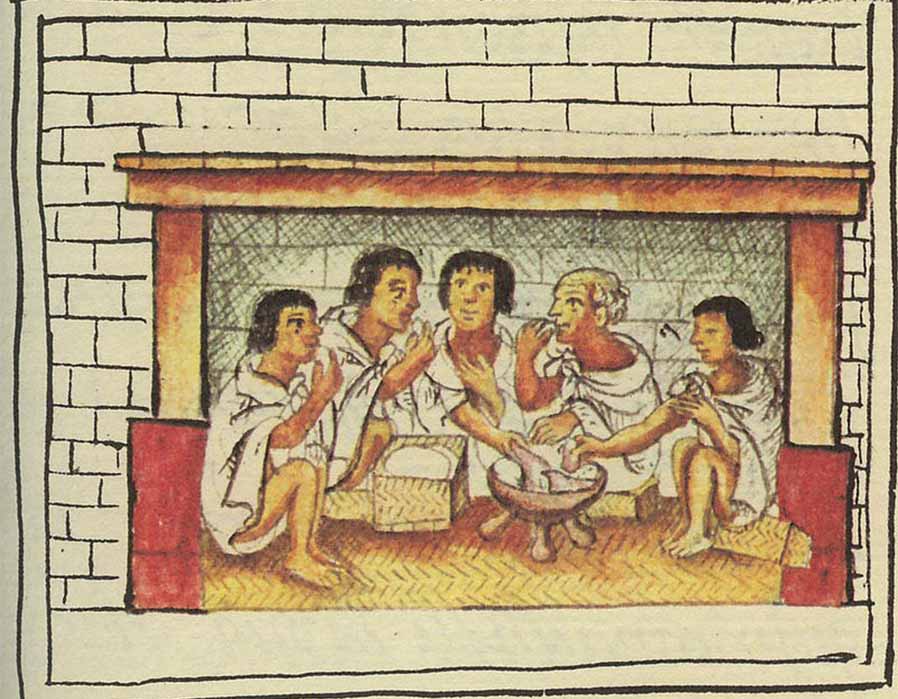

Aztec men sharing a meal. Florentine Codex, late 16th century. (Public Domain)

In prehistoric South and Central America the modern concept of ‘health foods’ and ‘superfoods’ did not exist, but without the presence of specific foods packed with nutrition many of the past civilisations would never have achieved the agricultural, architectural and cultural heights that is evident today in their respective temples, monuments and growing terraces. Among the gastronomic histories of South America and Mesoamerica a handful of special drinks became not only cultural traditions, but they were associated with deities and the spiritual destinies of entire civilizations.

Chia Seeds For Ritual And Running

At a glance, ancient Aztec (Nahuatl) people in pre-Columbian Mexico knew grey chia seeds (Salvia hispanica) with black and white spots indicating they were ready for processing, while brown indicated they were not yet ripe. Measuring around two millimetres (0.08 inches) chia seeds were a staple food for most Mesoamerican cultures and today it is still grown commercially and consumed in its native Mexico and Guatemala, but also across Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, Ecuador and Nicaragua. Furthermore, according to writer Claire Dunn is the 2015 Sydney Morning Herald article titled Is chia the next quinoa? a range of new patented varieties of chia have been developed in Kentucky for cultivation in northern latitudes of the United States.

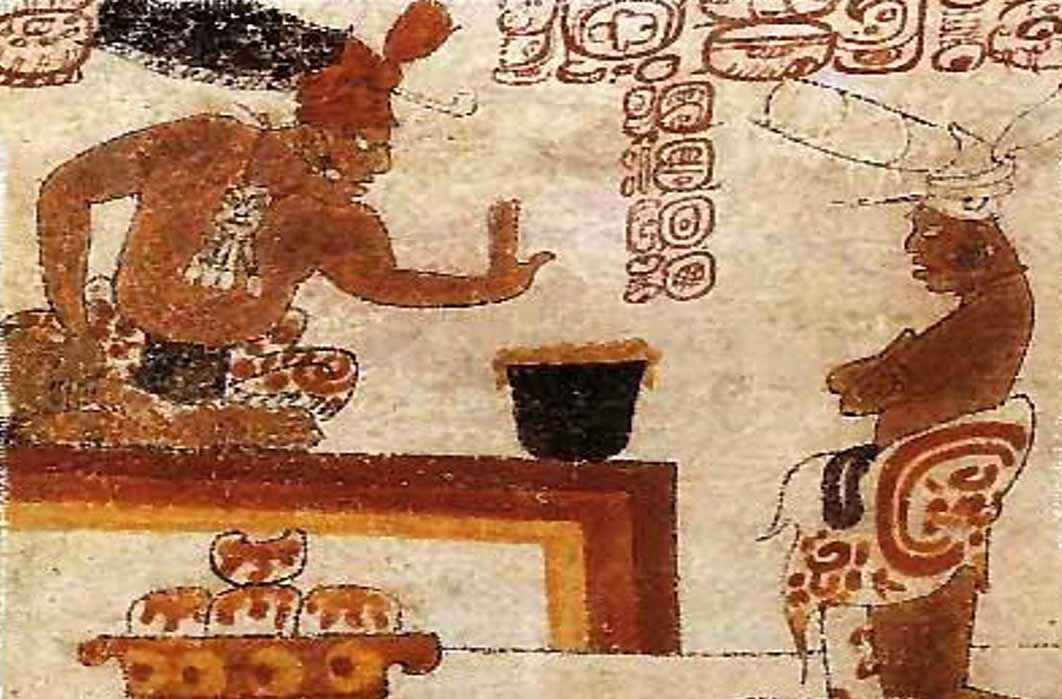

Drawing from the Florentine Codex showing a Salvia hispanica plant (Public Domain)

Being hygroscopic, chia seeds absorb up to 12 times their weight in liquid from the air and this is why they have a mucilaginous (thick gel like) coating that defines the texture of chia-based foods and beverages. The knowledge that pre-Columbian Aztecs cultivated chia seeds comes from the Codex Mendoza written around the year 1541 AD. Named after Don Antonio de Mendoza, the viceroy of New Spain, and written in the Nahuati language, this particular codex details not only the successful military campaigns of the ruling Aztec elite, but also the day-to-day goings-on of common people in society. Just behind corn and beans, so valuable were chia seeds in Aztec society that they were given in vast tonnages by farmers as annual tributes to elites in no less than 21 of the 38 Aztec provincial states.

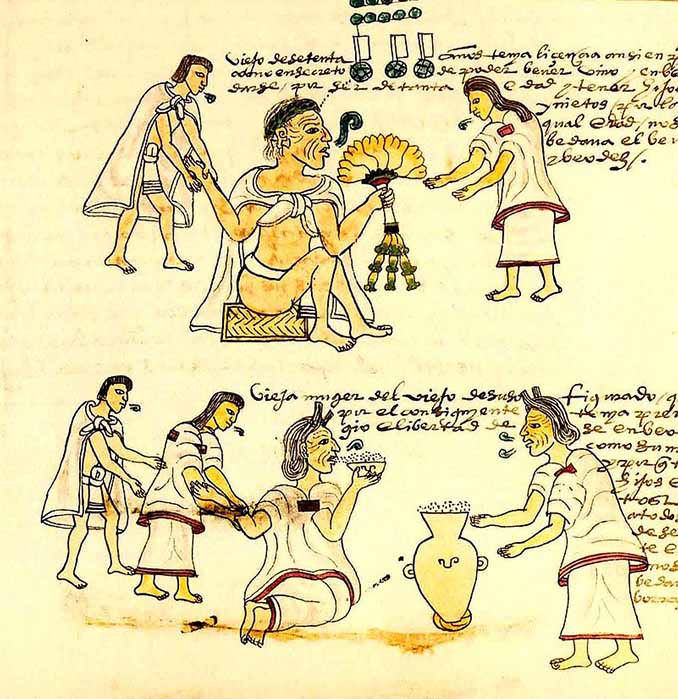

A painting from Codex Mendoza showing an elderly Aztec woman drinking pulque. (Public Domain)