Alexander Nevsky – Medieval King Turned Russian Propaganda Tool

Nestled deep within an obscure crevice of Russian history, the tale of Prince Alexander Nevsky and his battle against Western crusaders at first appears as a highly interesting if half-forgotten turn of events, tracing the resilience and mettle of a lesser-known Slavic kingdom located on the fringes of Europe and Asia. Yet this story, at least the official version, is known to millions of Russians today, and has over the last few centuries embedded itself deeply within the narrative of the Russian State as a powerful metaphor, representing their eternal struggle against the West.

13th-century Novgorod as represented in Sergei Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (1938). (Public Domain)

Even today, Alexander Nevsky, a commander of valor and honor who repelled the Mongolians, Swedes, and Germans from the lands of Novgorod, is invoked by Russians fighting in Ukraine who believe their aggression is actually a form of defense against the further incursions of the Western world. Yet a closer examination of his story, and the thrilling sagas of the Battle of the Neva and the Battle on the Ice, reveals a man more concerned with bravely resisting the advances of foreign forces than warmongering.

The Tavastian Crusade

During the late 1220s and early 1230s, crusades against the pagans of Baltic Europe were put on hold because of a power dispute between the King of Denmark, Valdemar II, and the Sword Brothers, a motley order of crusading knights from Germany, over the territories of modern-day Latvia and Estonia.

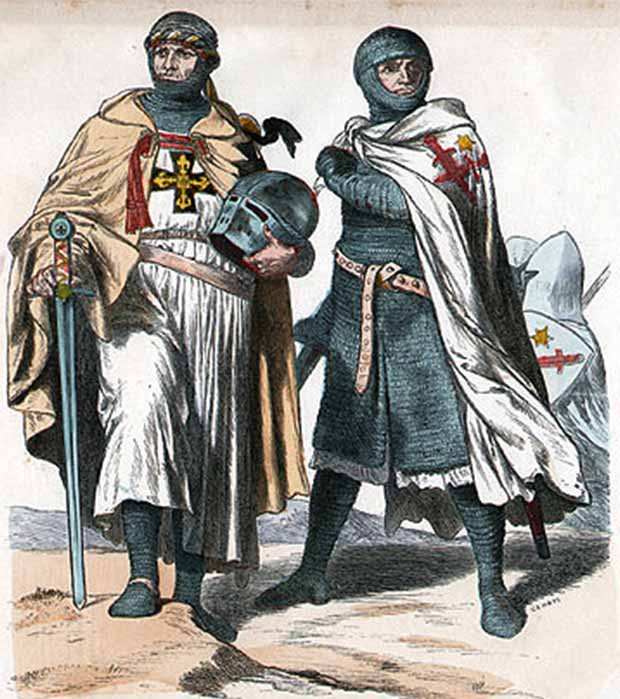

A Teutonic Knight on the left and a Sword Brother on the right. (Public Domain)

The Sword Brothers had stubbornly resisted demands by the Papacy to handover Estonia to the Danes, whose armies had been chosen by the Pope to represent and expand Christian influence in an area that was still teeming with pagan heretics. The Sword Brothers had not helped their position by slaughtering papal representatives based at the Bishopric of Leal in 1233, as well as destroying a Cistercian Monastery with the help of local indigenous tribes and Russian apostates.

In response, a Papal bull was issued in 1236 demanding that the Sword Brothers relinquish control. It was only in 1238, after the Sword Brothers had been wiped out after a disastrous foray into heathen Lithuania, that the Papacy was able to finally reestablish order with the signing of the Treaty of Stensby, granting all Estonian lands to the Danish Crown.

As the Papacy were concluding affairs in the region, they started to consider the direction of future campaigns, calling on other Scandinavian countries to step-up their involvement in the Baltic Crusades. In 1237 the Swedes answered, and a bull was proclaimed permitting the Archbishop of Sweden to crusade against the Tavastians, a native people inhabiting current-day Finland. Yet, the Pope’s real target was the Kingdom of Novgorod, schismatic Christians who followed the doctrines of the Orthodox Church and who exercised overlordship over the Finns.