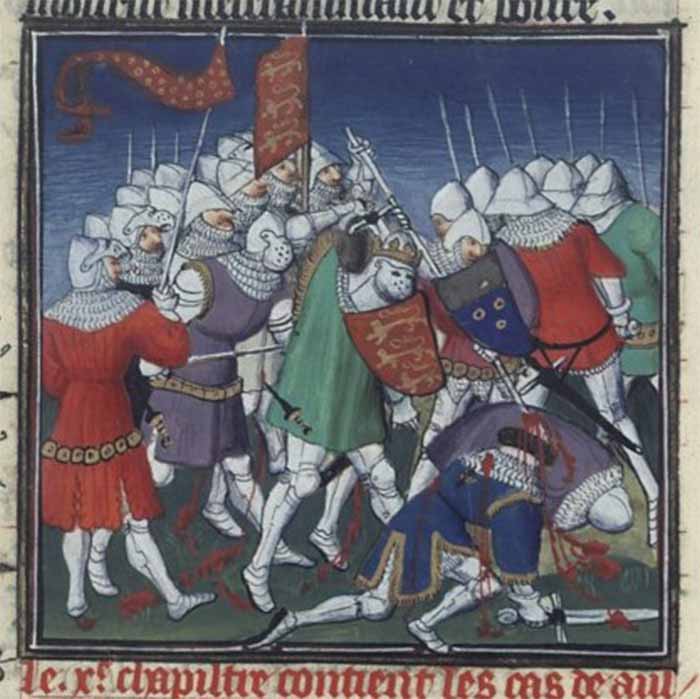

12th-Century Royal Succession Turmoil: Societal Taboo Against Fratricide

In 1106, King Henry I of England captured his elder brother, Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, during their decisive clash at the Battle of Tinchebray. While Robert Curthose’s capture provided Henry I with the necessary leverage and military prestige to annex Normandy and usurp the title of duke, the king was now presented with the serious dilemma of what to do with his deposed sibling. Even captured and momentarily humbled, Robert Curthose was a potential figurehead for any future aristocratic resistance to Henry I’s rule.

Battle of Tinchebray by Rohan Master (Public Domain)

As the eldest son of William the Conqueror, the now deposed Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy arguably possessed a superior claim not only to Normandy but England itself. Upon his death in 1087, the Conqueror’s Will had stipulated that his patrimony, those lands he had inherited from his own father, be inherited by his eldest son Robert Curthose. Meanwhile the throne of England, which he had nominally inherited from his cousin, Edward the Confessor, and secured through military enterprise, was bestowed upon his second eldest surviving son, King William II Rufus.

Historians have long speculated that this decision may have been informed by Robert Curthose’s participation in an armed rebellion against his father. At the time of the Conqueror’s death, inheritance practices were in a state of considerable flux and far from proscriptive. While aristocrats during this period had in theory significant leeway in the manner in which they disposed of and allocated their landed interests, in reality they had to contend with the practical considerations of what their various relatives and those relatives’ supporters would be willing to accept. In the absence of a strong legal tradition or singularly recognized convention, the distribution of inheritance was ultimately a matter of negotiation and compromise.

The ultimate result of the Conqueror’s Will was that a number of the Anglo-Norman realm’s leading magnates, including the late king’s half-brothers, felt that Robert Curthose had been cheated of his inheritance and rose up in defense of his claim. King William II (Rufus) succeeded in quashing this uprising but his relationship with Robert Curthose remained at its core strained and was characterized by intermittent outbreaks of violence, as one or the other attempted to consolidate the family’s holdings under their rule and displace their rival.

Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, by Henri Decaisne (Public Domain)

Brother Against Brother

When King William II (Rufus) died childless in 1100 leaving his brothers Robert Curthose and Henry I as his only heirs, there was no legal provision or custom that stipulated that Robert Curthose’s earlier relegation from the throne of England was necessarily permanent. Indeed, as the eldest brother there was a strong case to be made that Robert’s claim to the throne was superior to Henry I’s. As Duke of Normandy, Robert’s claim was further bolstered by the desire amongst many of the cross-channel Anglo-Norman magnates for a political reunification which would spare them the burden and dilemma of divided loyalties. In fact, Henry I was well aware of the weakness of his position and the likelihood that any extended process of arbitration would result in Robert Curthose taking the throne. It was for that reason that he moved with such alacrity and boldness. Upon hearing of King William II Rufus’ death Henry I seized control of the royal treasury, secured himself a bride of valuable royal pedigree and rushed ahead with his coronation in London. Once again, significant portions of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy came out in support of Robert Curthose. Rebellion and armed conflict were widespread, if poorly coordinated, and King Henry I retained his grip on power in England only by the narrowest of margins.