Translating Saint Etheldreda, A Tawdry Tale Of Medieval England

Etheldreda – St Audrey - is a familiar figure, especially so in Ely, a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire district, England. 2023 commemorates the 1,350th anniversary of her founding her monastery after running away from her second husband, Ecgfrith, King of Northumbria. Etheldreda was a princess of a royal house, related to the king who was buried at Sutton Hoo, revered as a saint for centuries after her remains were translated from her original grave by her sister (another queen) to a new shrine - but who was she as a person? What sort of world did she inhabit?

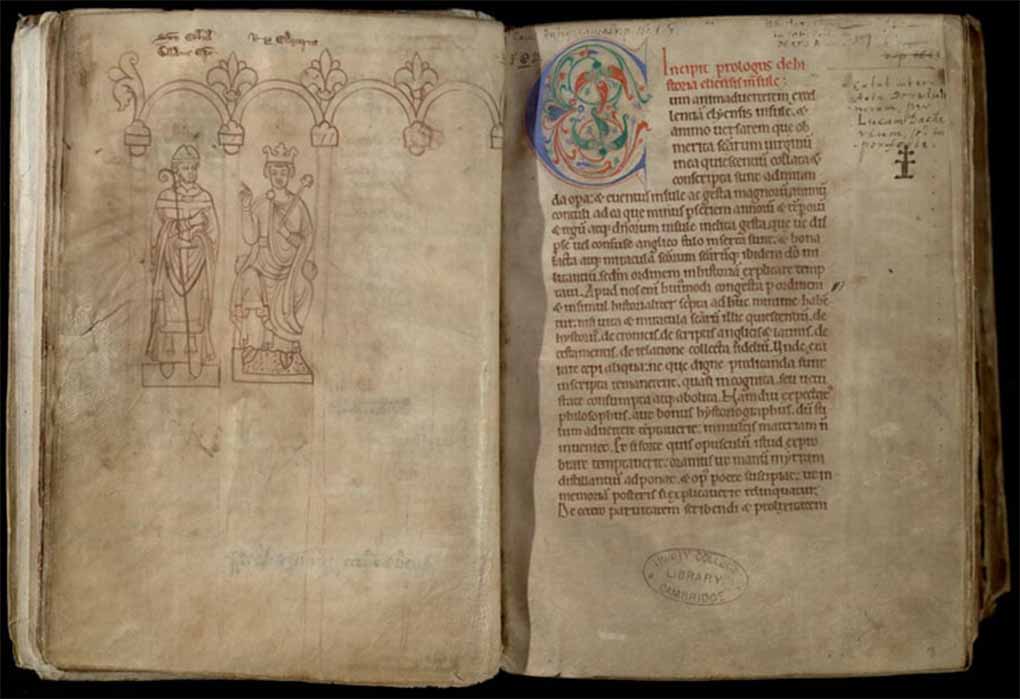

The ancient Liber Eliensis manuscript tells the dramatic tale of Aethelthryth’s tearful, passionate pleas to her husband for the freedom to pursue her yearning desire to serve her one true love: the “celestial Bridegroom,” Jesus Christ. ( Public Domain )

As it happens, in Old English Aethelthryth - Etheldreda - means ‘Noble Strength’, which is appropriate for a woman who must have been pretty tough, with the confidence and authority to get her way. But the word ‘translation’ has more than one meaning: it refers to the technical term for moving the relics of a saint to a new place, but it also means to translate the legends that provide a glimpse of the sheer otherness of her life; the mindset and times of this remarkable woman, literally and figuratively to a modern audience, who can hardly comprehend her very different world.

The Family Business of Not-Yet-England

Etheldreda’s world was not yet a recognizable England, by modern standards. Very few of the social markers, or even the material ones that are taken for granted today, were there. No matter how much is known about it, or how much is reconstructed in imagination, one can never really communicate or feel what living in those times was actually like and the distinctly different world of the extraordinary sixth and seventh centuries will always seem to have transpired in a remote, other country.

The Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. Bartholomew's A literary & historical atlas of Europe (1914) (Public Domain)

Etheldreda’s people, the Angles, had only been in Not-Yet-England for about six generations when she was born in the 630s AD. Using the term ‘Not-Yet-England’ reminds one that there really was not very much in England, in any sense, that would be familiar today. Even many of the animals, plants and trees were different, for example few of the table vegetables existed, no horse-chestnuts towering their spring glory, no weeping willows until the 1700s and no prolific sycamores. Salmon was so common that few wanted to eat it; beavers dammed up the rivers, and in the wastelands the howl of the wolf chilled the blood and set the sheep bleating.

In a relatively short time, the Britannia the Romans left to its own devices in 410 AD was divided up between the families of the Angles and Saxons and Jutes into Seven Kingdoms, the Heptarchy, and the ruling families in these little kingdoms were all related to each other. Everybody was somebody else’s uncle or aunt. Not-Yet-England was actually more like a family business, and wars, however bloody they might have been, were just supersized family quarrels. There were also far less people about – around two million at the most in 1066 – so everybody who was anybody knew everyone else who was anybody, which makes for a different mindset, compared to today’s anonymity.

One can to some degree conjecture, through its material remains, what it must have been like to grow up in that Anglian culture – distantly reflected in Beowulf - that had migrated from the other side of the North Sea, but the mentalité is another matter.