The Other Arthur Of England: Pendragon Or Tudor?

For over 300 years, and probably more besides, the fabled figure of King Arthur had set the standard for English kings to follow. The victorious son of Uther Pendragon was, in the words of Geoffrey of Monmouth, the conqueror that ‘no country could resist.’ Kings came “of their own free will to promise tribute and to do homage.” Arthur held more than the hopes of heroism. His was a tale of caution. Camelot’s king knew what it was to be betrayed and abandoned. He suffered defeat and humiliation. He had even been made a cuckold. Any king that made Arthur his example was one who would never let a crown rest too easily on his head. Defeat could follow even the most glorious of victories.

Tapestry showing Arthur as one of the Nine Worthies, wearing a coat of arms often attributed to him (c. 1385)(Public Domain)

Towards the end of the 15th century, the tales of King Arthur, Camelot and his knights of the round table had acquired a new significance in England. The stories of a king who could triumph over his enemies, only to be betrayed by those nearest to him, found a new poignance in a half century where kings rose and fell with unprecedented pace. Yet, just as Arthur’s tales were flourishing in literature, a new wave of men was seeking to expunge him from the history books. These men fostered a new form of learning, called “renaissance humanism”. They were adamant that this treasured king of the Britons was nothing more than a myth.

Henry Tudor, A Fan of Arthur

But there was at least one humanist who disagreed sharply with this reassessment. His name was Henry Tudor, and thanks to his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, he had emerged victorious in the dynastic wars which had raged in England for 30 years. To the newly crowned Henry VII, King Arthur was far from a fable. He was family.

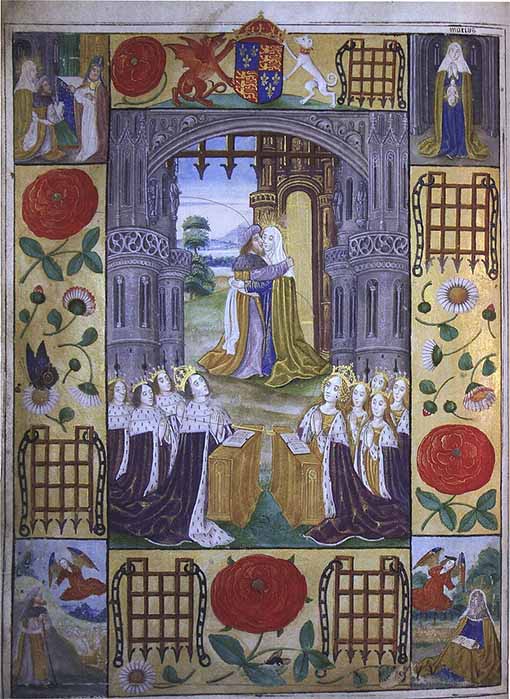

The family of Henry VII with Joachim and Anne meeting at the Golden Gate. The flowers are Marguerites (daisies), for Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII. Red Rose of Lancaster (Public Domain)

The Tudors, like all newly enthroned dynasties, were on a quest for legitimacy. And it was in their Welsh ancestry that they searched for it. They descended, so they claimed and probably believed, ‘from the ancient Briton kings’ making them the true heirs of Brutus, Cadwaladr and most significantly, Arthur himself. The Tudors were no new dynasty. They were the restorers of the true line of kings. In the wilder moments of Tudor propogandists’ imagination this made Henry VII not just a legitimate king. He was the first legitimate king for over 800 years.

- How Henry VI Genetically Engineered Henry Tudor for the Throne

- What was Sweating Sickness, the Mysterious Tudor Plague of Wolf Hall?

- Bed Bought Online for £2200 May be 15th Century Bridal Bed of King Henry VII

This, of course, was just imagery. Henry’s true claim to the throne came from being the tenuous but just-about-credible heir to the House of Lancaster, which had ruled England for 60 years from the turn of the 15th century. He had bolstered his claim immeasurably by quickly marrying Elizabeth, the heir to the House of York, which had usurped the Lancastrians in 1461.