Papyrus Rolls Rolling From Egypt To The Roman Empire

By the first century AD, papyrus paper was available throughout the Roman Empire, a market that consisted of the area stretching from Hadrian’s Wall in the northern wilds of Caledonia, east to the dry karst plateaus of Cappadocia and the Caspian Sea, south to the lush valley of the Nile, and west to Lixus in the deserts of Mauretania. An empire of over two million square miles surrounding the Mediterranean, Mare Nostrum, “our Sea” and comprising a population of almost 100 million people, it had an enormous daily demand for food, drink, and paper. To make things easier, the Romans simply made Egypt a province. In so doing they were formalizing a long-standing arrangement. Egypt had been a major supplier of grain for many years. But even though Egypt was now a province, it was still a major trading partner.

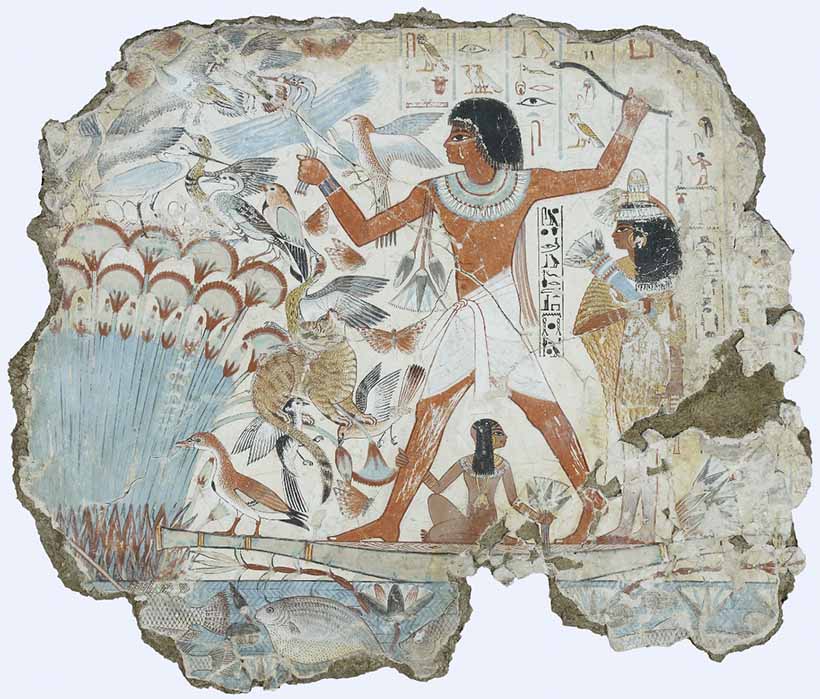

Nebamun, a middle-ranking official ‘scribe and grain accountant’ during the New Kingdom is shown hunting in the marshes, in a scene from his tomb-chapel. British Museum (Public Domain)

In exchange for luxury imports and raw materials such as gold coins, glassware, olive oil, wool, purple fabric, metal weapons, and tools, Egypt exported gold, linen, glass, painted pottery, papyrus paper, and rope. For years Egypt also sent grain, which fed the ports, cities, and populace of Italy, but grain shipments were essentially a tax in kind sent to Rome instead of money. The amounts rose to more than 100,000 metric tons per year under the first emperor, Augustus. For many items other than grain, the export business was a two-way street and thrived on finished products in preference to raw materials. Egyptian exporters saw it as an opportunity to export value-added items, a practice that goes on in many countries today as well as it did in ancient times.

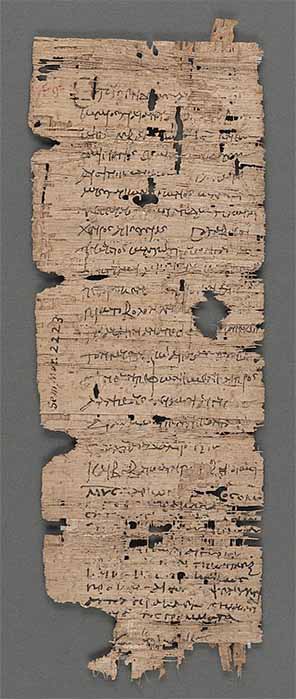

Bill of sale for a donkey, papyrus; 19.3 by 7.2 cm, (126 AD) Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public Domain)

Exporting Papyrus Rolls

When papyrus paper left Egypt in sheets or rolls bound for the Roman markets, it represented a marvelous example of the value-added principle. Papyrus paper needed little or no input, unlike grain that was sent raw to be ground into flour by the Roman mills, gold that needed to be refined and recast, or glass and linen that required much initial work, and in the case of producing glass, pottery, and refined gold, fuel was needed in a country where wood was scarce. The kilns and furnaces in Egypt often used chaff, waste from grain milling, dried papyrus stems, and as a last resort local bushes and stunted trees from arid regions. In the case of paper, it was a finished product that was cheap to make and used local resources that were self-sustaining. It was also a product that was kept under close watch by a cartel of plantation owners who harvested year-round and kept the paper factories operating 12 months a year.

Under Roman administration, Egyptian papermakers were subjected to strict quality controls as paper was now graded against standards set by Rome. The cartel rose to the occasion and produced whatever was necessary, from the high-quality paper of the imperial grades down to the lowest form used as wrapping paper. They were so successful through the years that it was even suggested that Firmus, a Moor ruler in Muretania who set himself up as an imperial pretender in 273 AD (a position from which he was later deposed), might have been heavily invested in the Egyptian paper trade.

Men harvesting and working papyrus in the tomb of Puyemre (ca. 1479–1458 BC). Reproduction Hugh R Hopgood. Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)