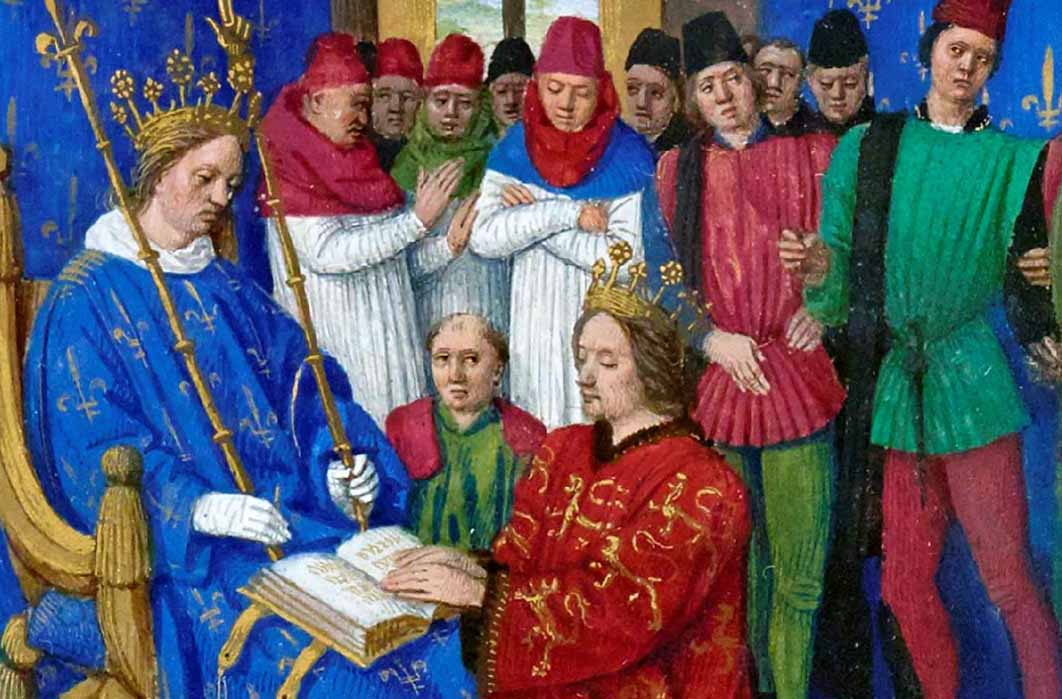

Clash Of Kings: England’s Edward Longshanks Versus France’s Philip The Fair

The Anglo-French war of 1294-1303 has not been the subject of a major study since the early 1900s. Recent histories tend to treat it as a sideshow compared to King Edward I’s wars in Wales and Scotland, which gives a false impression. In reality the Welsh and Scottish campaigns were distractions, and King Edward regarded the war against France as his main focus. The main issue at stake was the defense and recovery of Aquitaine, the last substantial piece of the so-called ‘Angevin empire’. To that end King Edward spent enormous sums of money on recruiting allies in the Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire. King Edward’s rival, King Philip IV of France, also recruited allies to counter King Edward, until the conflict engulfed much of Western Europe. The result was a series of military stalemates, demonstrating that neither England nor France could achieve outright victory in a head-to-head conflict. The contrast in the ambitions of King Edward I of England and King Philip IV of France and their rivalry compelled the Anglo-French war of 1294–1303 and the far-reaching consequences that lay beyond.

King Edward: Crusader and Tournament Fighter

In the mid-1280s Edward was at the height of his powers, respected at home and abroad. Since he came to the throne in 1272, he had been remarkably successful. The King had put an end to conflict in England, united the baronage and implemented a vast programme of legislative and judicial reform. He had recently completed the conquest of Wales – a feat that eluded his predecessors – and stamped his authority on the Welsh with a series of mighty castles. Overseas Edward had clawed back lands in France and did wonders for his reputation by going on a crusade. His venture to the Holy Land brought little material reward, but unlike virtually all his peers he could boast of having actually set foot in Outremer. He had risked his skin in the defense of the Christian states, and carried the scars to prove it.

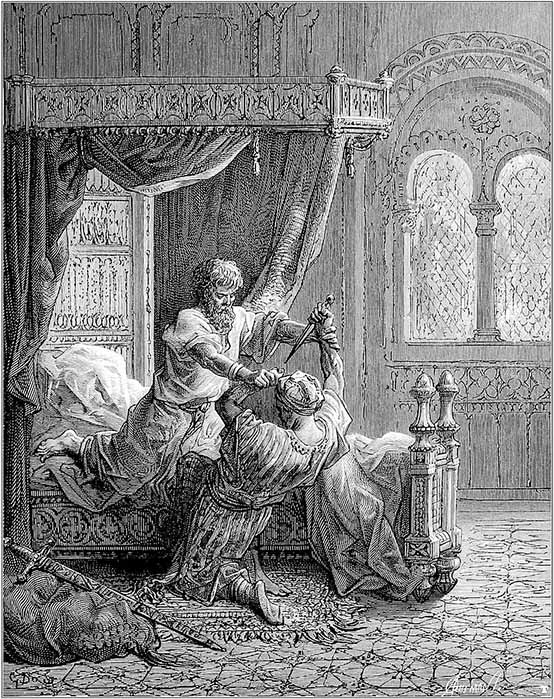

Edward I kills his attempted assassin on crusade in Acre by Gustave Doré (Public Domain)

Edward also enjoyed the reputation of being a skilled tournament fighter, praised by troubadours for his martial prowess. Peire Cardenal, a southern French poet, exhorted Philip III of France to follow Edward’s heroic example on crusade: “I beseech all to pray sincerely to God, Jesus Christ, That he may grant joy to Lord Edward over there, As he is the best lance in the whole world, And grant to King Philip the heart and desire to assist him soon.”

In 1274 the Pope had formally prohibited Edward from taking part in any more tournaments, but his reputation persisted in France. The French poet Sarrasin, composer of La Roman du Hem, an account of a tournament in France in 1278, had this to say of the King and his knights: Here [in England] you will find good fighters, hard men, tough and strong. Lancelot and Gawain and the men of the Round Table, who were the best in the world. There are knights of reputation, there are many good jousters, there are brave knights … and him who is their lord and king, the valiant, generous and benevolent King Edward”. Edward’s reputation was also high south of the Pyrenees. Ramon Muntaner (1265–1366), a Catalan mercenary and chronicler, described Edward as ‘the most acceptable king of the world, as he was one of the most upright Kings of the world and a good Christian’.

King Edward I. (Willud Edier / Public Domain)

Presenting King Edward Longshanks

A vivid physical description of Edward is supplied by Nicholas Trivet, a Dominican friar who may have actually met the King and was certainly involved with the royal court: He was a man of tried prudence in affairs of state. He was devoted in adolescence to the practice of arms by which he acquired a widespread reputation for chivalry – his fame excelled every prince of his time. He was elegant of form, of commanding height, exceeding an ordinary man from the leg upwards. His looks were enhanced by a beard which in adolescence turned from a silvery colour to hold, became black when he reached manhood, and in old age changed from grey to the whiteness of a swan. He had a broad forehead and regular features, except that the lid of the left eye was lower, recalling his father’s appearance. He had a lisp but was nevertheless effectively eloquent in speech when persuasion was necessary in business. His arms were long in proportion to his agile body, and none was more able, with sinuous dexterity, to wield a sword. His stomach protruded, and his long thighs made it impossible for him to be unseated by the galloping or jumping of the most spirited horse. When he had finished with fighting, he indulged in hunting and hawking. He especially hunted the stag, which he pursued on the courser and when he had caught one, he struck it with his sword instead of using a hunting spear”.

This paints an image of a man of action, with some notable physical oddities: Edward’s drooping eyelid, apparently inherited from his father, and his speech impediment. To judge from this, the King’s popular nickname of ‘Longshanks’ – referring to his height and long limbs – was well deserved.