Tragic Coriolanus, Roman Warrior Or Traitor

William Shakespeare’s Roman play Antony and Cleopatra impresses upon the audience a vast universe which includes Rome, Alexandria, and Athens. In contrast, his other Roman play, Coriolanus, is limited to the little universe of Ancient Rome before the height of the Roman Empire along with its rivalling neighbours, the Latin tribes only a few miles away. Coriolanus started with a group of rebellious Roman citizens fiercely accusing a man named Gnaeus Marcius of being the “chief enemy of the people”. In a relatively short period of time, this same Gnaeus Marcius was set to rise to prominence as a Roman war hero, come to be known by the name Coriolanus, banished as the people's main adversary, fulfil the accusations made against him by teaming up with the Volsci, Rome's enemy, and finally perish violently at the hands of his former allies.

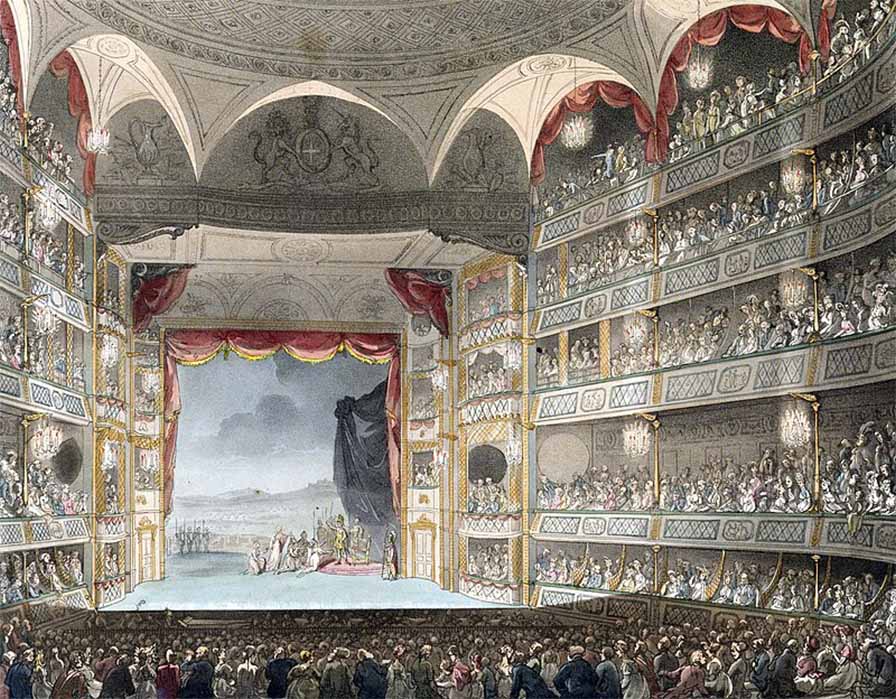

Shakespeare’s Coriolanus on stage at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (Circa 1808) (Public Domain)

Shakespeare’s Coriolanus was based on the life of Gnaeus Marcius Coriolanus, a legendary Roman hero of patrician descent who is thought to have lived in the late sixth and early fifth century BC. Legend has it, his surname came from his valour at the siege of Corioli, during the Battle of the Volsci in 493 BC. The Volsci were members of the Osco-Sabellian group of tribes who lived in the upper Liris River valley since approximately 600 BC. They were also important to the Roman expansion narrative in the fifth century BC. During Rome's famine in 491 BC, Coriolanus spoke against giving grain to the populace unless they agreed to abolish the office of the tribune. The tribunes sentenced him to banishment because of this. Soon after, Coriolanus sought refuge with the King of the Volsci and led the Volscian army against Rome, retreating only after his mother and his wife pleaded for him to do so. Like in the play written hundreds of years later, it was among the Volsci that Coriolanus died.

Backdrop to the Legend of Coriolanus

The two conflicts that characterized Coriolanus' career were the Battle of the Orders and Roman-Volsci War, both of which were the outcome of Rome's republican transition, a significant event that occurred at the close of the sixth century BC. Just before 500 BC, two royal princes, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and Lucius Junius Brutus, drove King Tarquin the Proud from his city. As soon as they had a falling out, Collatinus was banished from Rome. Not long after Collatinus’ banishment, Brutus was killed in combat against King Tarquin's Etruscan allies. Nobleman Publius Valerius Publicola declared he would share his authority with a co-consul and soon became the next ruler of Rome. From this point on, Rome was governed by two consuls who were often aristocrats.

As King Tarquin had forced the surrounding towns of Latium into submission, Rome was severely wounded by the revolution although it only lasted for a little more than a year. The cities now rebelled and cried out for their independence. However, they were vanquished by Aulus Postumius Albinus, the first dictator of Rome, and a new pact was made. An even more difficult issue soon surfaced as, in search of greener pastures, the mountain tribes of the central Apennines descended to Latium once more after previously being turned away as they were trying to reach the coastal plain. The divides among the Latin tribes were effectively exploited by the Aequi and Volsci. With ease, the towns in the east and south were taken, and the battles among these tribes became annual occasions. Coriolanus was to become renowned in this seemingly never-ending conflict.

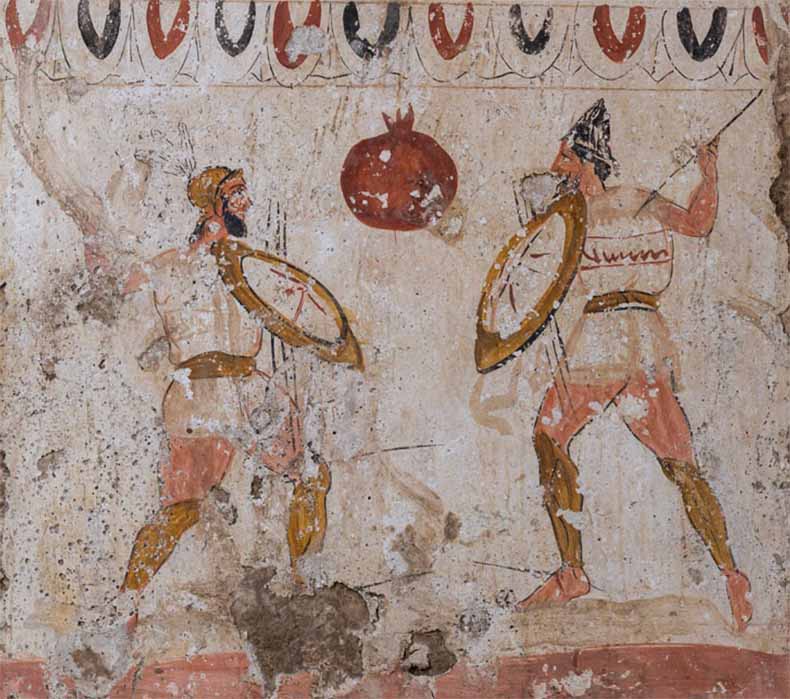

Divides among the Latins: Duel of Lucanian warriors, fresco from a tomb (fourth century BC) Paestum, National Archaeological Museum (ancientrome.ru/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another issue was that, although the aristocrats had taken the position of the King, the republic had not benefited most Romans. It appears that Italy experienced an economic crisis on a wider scale. Although the exact nature of the crisis is unknown, there appears to have been less imports from Greece, the quality of the imported items was bad, and the historical record of the era is scant. The privileged and the impoverished experienced societal conflicts, resulting in a debt crisis.

In 490 BC, the plebeians began to seek better living conditions. To protect the rights of the impoverished, the plebeians established the position of tribunus plebis (“Tribune of the Plebeians”). They then pledged under a lex sacrata (holy law) to protect the tribune's person at all costs and thus rendering him impervious to assault from the magistrates. This gave the tribune the power to veto decisions made about finances by quaestors, sentences by praetors, and measures by consuls without concern for his own safety. Following a brief altercation, the aristocrats acknowledged the tribunes, but they insisted that they refrain from military interferences. Thus, the tribunes were, in a way, anti-magistrates elected by the people's assembly.