The Giza-Tesla Connection Explored

With no, or slim, evidence, Egyptologists claim that all of Egypt’s pyramids were built to be tombs. With an abundance of robust evidence, I will theorize that all of Egypt’s pyramids were built to serve a more practical purpose, that is to harvest electrons contained in igneous rock in the Earth’s lithosphere.

The fundamental science that supports the Giza power plant theory is the same understanding of nature that is embodied in every other pyramid in Egypt. It is, as Ahmed Adly specifically noted, “the power generated from an exceptional understanding of the physical properties of the rocks.” While Adly was referring to the ancient Egyptians’ presumed knowledge and understanding of rocks, today, fortunately, we have scientists who, in my opinion, have recovered that lost knowledge—and what they have discovered has the potential to transform the planet in ways we cannot even imagine.

When Rocks Go Crunch

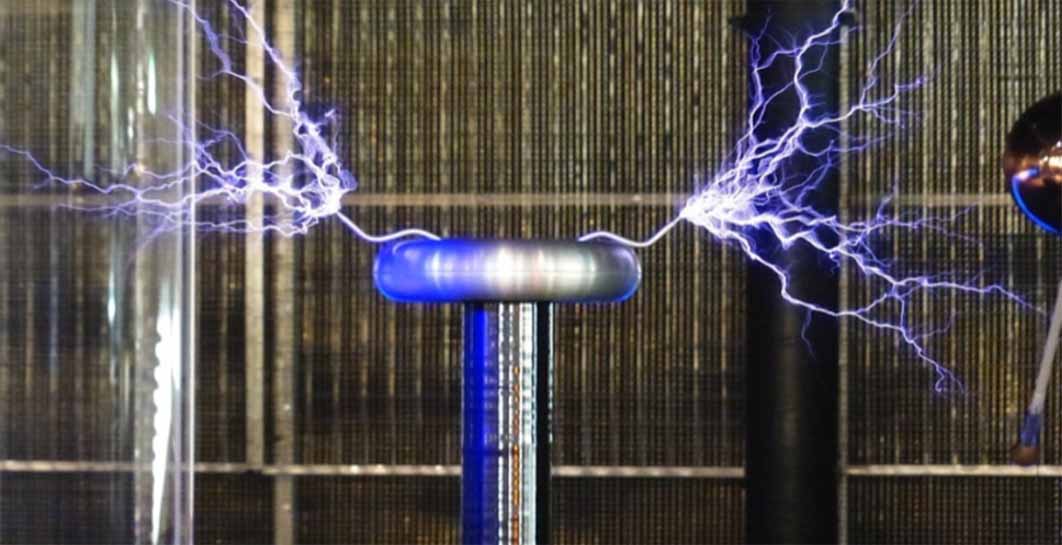

In The Giza Power Plant, I described the King’s Chamber as a resonant chamber that, because of its material makeup, converted mechanical energy (vibration) to electrical energy. I quoted the work of other authors who claimed that the Aswan granite out of which the chamber was constructed was composed of feldspar and up to 55% silicon quartz crystal. With the quartz crystal subject to vibration, I theorized that the piezoelectric effect of the crystal was responsible for generating electron flow.

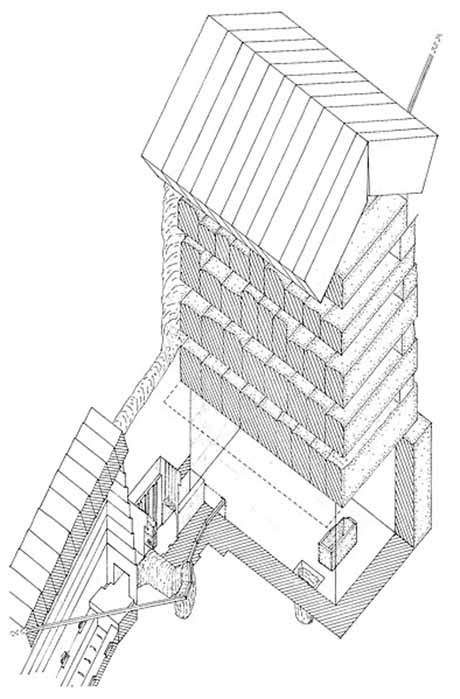

Because of the features and dimensions of the North Shaft that make it suitable for use as a waveguide for microwave energy, I posited that the King’s Chamber complex and its shafts connecting to the outside would serve as a maser (microwave amplification through stimulated emission radiation.) The key evidence to support this theory are the North Shaft, with dimensions suitable for hydrogen radiation, and a bulbous opening in the south wall, shaped like a microwave horn antenna, that collected the amplified energy stimulated in the resonant King’s Chamber.

Axonometric view of the King's Chamber. (MONNIER Franck ([email protected])/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In order to activate piezoelectricity, quartz has to be stressed across a specific axis, and the random orientation of crystals in the granite do not support the idea that piezoelectricity was a significant factor. While questions persist regarding the percentage and orientation of quartz in granite, with estimates ranging from less than 20% to over 60%, the entire discussion may be irrelevant.

In March 2018, I cohosted a Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt tour with sound engineer Robert Vawter and Egyptologist tour guide Mohamed Ibrahim. A think tank of guests was attracted to the tour, one of whom was geologist Adrian Lungan, who graduated with first-class honors from the University of Western Australia and has had a successful 40-year career in the mining industry. I was particularly impressed with his study methods at the Aswan quarries, when he picked up a piece of granite, studied it closely under a lens, and then put it to his mouth and licked it. Employing his taste along with sight and touch provided him with more information about the material makeup of the rock. Upon reflection, I was curious about this method, so I emailed him and asked about this as well as his analysis of the amount of silicon quartz crystal in Aswan granite. On August 31, 2021, he responded:

The Aswan granite is an acid-syenite which has a very specific composition in that the quartz content is very low (<5%). Robert Vawter and I discussed the piezo-electric properties of the quartz in the Aswan granite, and I pointed out that just because a rock contains quartz, it doesn’t mean that all quartz in say, a granite, exhibits piezo-electric properties (i.e. mono-crystalline vs amorphous quartz) and with such a minor amount of quartz in the granite, I don’t believe that the electrical properties would in any way be highly significant.

On licking rocks, when a rock is altered e.g. via hydrothermal fluids or by weathering, then certain clays can form. By seeing if your tongue sticks to a clay-rich rock, one can determine if the clay is kaolin (i.e. the rock has been kaolinized) or not and one may be able to work out what the clay was probably derived from and hence, the precursor. Also, when one crunches, say, a siltstone between the teeth, it feels ‘gritty’ when moving your teeth from side to side, whereas a mudstone feels smooth so, when not apparent, you can bite off a small fragment of the rock and use your teeth to determine the difference between the two rock types. Some rocks you definitely don’t lick, e.g. rocks with brightly colored minerals, e.g. mercuric minerals such as cinnabar or arsenical minerals. Many of these poisonous minerals, except for scorodite (As), are brightly colored, reds, oranges and yellows, so when you see distinct minerals with such colors, it’s not a good idea to lick the rock. Most geologists should recognize them. (Adrian Lungan email received on August 23, 2021)