Beyond the Cut: The Historical and Cultural Significance of Hairstyles and Barbershops

The pandemic in 2020, which shuttered hairdressers for most of the year, led to numerous unexpected hair trends such as buzzcuts and fringes. The much-derided mullet also made an appearance. This historical haircut, worn by both men and women, is regaining popularity among people who consider themselves fashion rebels, refusing to conform to standard expectations.

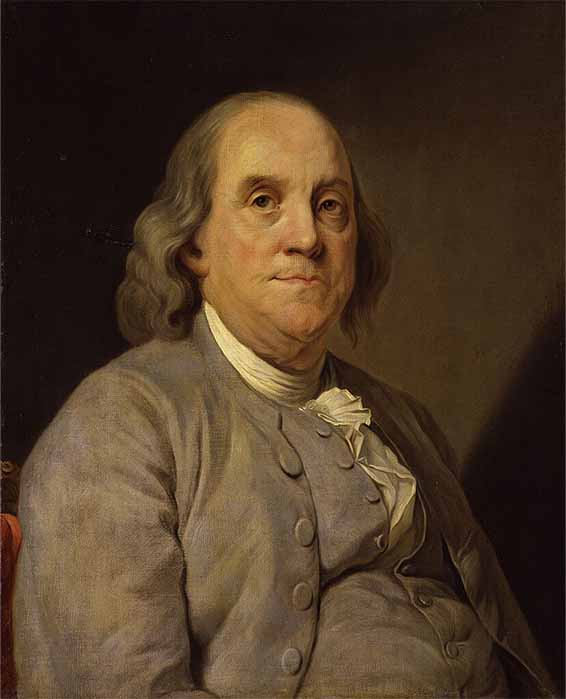

Although the term “mullet” was only coined around 1994, the hairstyle itself has made numerous appearances throughout history. In the early 1970s, David Bowie's signature orange haircut, part of his "Ziggy Stardust" character, became a defining image for a challenging decade highlighted by Watergate and the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster. Earlier, in the late 18th century, despite his own cosmopolitan upbringing, Benjamin Franklin skilfully played the role of a down-to-earth, new-world sage to persuade France to increase its financial and diplomatic assistance for the United States in its early years.

A portrait of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Siffrein Duplessis. (Public Domain)

At a time when status was measured in finery and tall powdered wigs touching the roofs of royal carriages, Franklin cuts an unusual figure with his plain unpowdered hair in which the hair in the back is left long but the top and sides are very closely shaved, if not left completely bald. Further looking the part, he also wore a modest brown suit to greet the king rather than covering himself with silk and medals. His astute self-promotion emphasised simplicity and equality while denouncing the excesses of France's at the time aging and increasingly out-of-touch monarchist class. His ideas and mannerisms would subsequently gain traction among French rebels.

- Big Wigs and Hairpieces: Artificial Hair of the Ancient World

- Dress like an Egyptian: Fashion, Style and Simplicity in Ancient Egyptian Clothing

From a Practical Military Choice to a Sign of Multiculturalism

What we now know as the mullet likely has its roots as a practical military haircut. The idea was to have long hair in the back to keep one warm on an exposed battlefield and having it shorter in the front which ensured that the soldier would not have hair in their eyes and to deny their opponents the opportunity to pull their hair in a close-range combat.

In his Life of Theseus, Plutarch writes that the ancient Abantes of Euboea were warlike and close-in combatants. Plutarch also claimed that the Abantes were the first to shave the front of their heads to prevent their foes from gaining a foothold in battle. The Iliad 2.542 also references the Abantes' reputation as close-in fighters. Homer also characterised their hair with the legendary phrase, "their forelocks cropped, hair grown long at the backs." Strabo quotes the Iliad to illustrate the ancient Euboeans' hand-to-hand combat abilities. He also cites historian Archemachus (3rd century BC) in noting that the Curetes settled at Chalcis. In the constant warfare over the Lelantine plain, they let their hair grow long behind, but cut it off in front to deny their opponents a handhold. It seems apparent that Strabo recognized the Curetes as the same Abantes referred to by Plutarch.

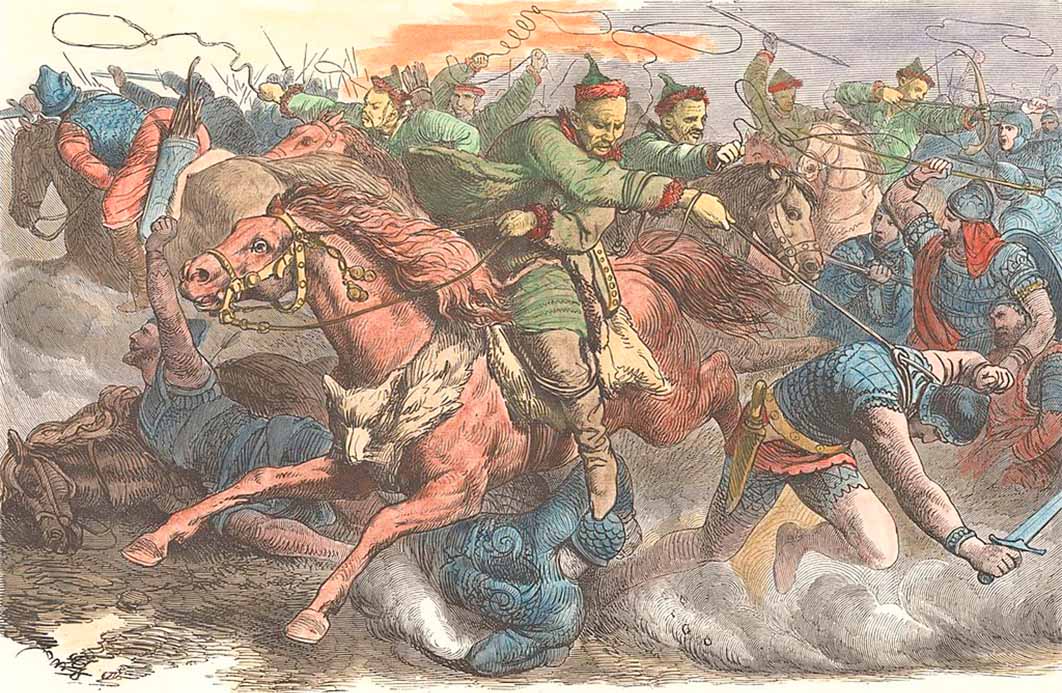

In the Roman world, at least according to how the ancient Romans tell it, the landing of Huns at the empire's border was a complete disaster. A passaged etched on a wall in ancient Constantinople says that “the Huns in multitude break forth with might and wrath … spreading dismay and loss." The nomadic Huns, who lived over Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, were dubbed "treacherous," "scarcely human," and "the scourge of all lands." Historical sources, many of which were written long after the Huns' conflicts had ended, blamed them for Rome's demise and the subsequent Dark Ages.

The Huns' military campaign undoubtedly shattered the Roman Empire. However, the remains of over 200 Huns from five 5th century locations in Pannonia, a Roman frontier province located in what is now Hungary, had enough bones and teeth to be analysed to help determine who they were and how they lived. The scientists discovered that, while the Roman and Hunnic elites were at war, ordinary people living on the edges of these two empires were able to cohabit, if not cooperate.