Forgotten Vikings: D-Listers of the Viking Age

The Viking Age is a perennial subject for many, a period of about three-and-a-half centuries where the fortunes of various countries across northern Europe were forged out of fire, fury, bloodshed, economic growth, expansion, and all that jazz. Or at least, that is how it first seems; a constant ‘ramping up’ of scale and scope from an isolated raid on Lindisfarne in 793 to the final showdown at Stamford Bridge in 1066. This narrative, moving from raiders to invaders to crusaders, is one of the key tenets of modern storytelling about the Viking Age, covering such famous figures like Erik Bloodaxe, Harald Fairhair, Hardrada, Cnut the Great; some real, many not. But it is such famous figures - Viking Age celebrities - that overshadow and obscure some of the more interesting elements of the period. You’ve all likely heard of Mr. Bloodaxe, right? What about Knutr and Sigfrodr of York? Two kings who ruled about fifty years before him and were some of the first to implement Anglo-Scandinavian coinage in the capital. What about Bjorn Ironside and Ivarr the Boneless? Huge names. A-listers of the Viking Age. People will know who they are either through their perceived pseudo-historical impact or their enduring legacy throughout pop culture. But what about their contemporaries and like-minded kin? What about Sitriuc Silkbeard, Rorik of Dorestad, Bjorn of the Broadwickers? Characters large and small from sagas and chronicles, some ripped straight out of fiction and others embroidered into real political narratives of the ninth and tenth centuries.

To celebrate the release of Forgotten Vikings: New Approaches to the Viking Age - a book that tries to peel back many of the more obvious layers of the period - this article will run through several ‘lesser known’ (mileage may vary depending on your level of knowledge in the subject) figures from the 9th to 12th centuries and bring them into a new light. So, without further ado, let us move away from the celebrities of the Viking Age, and analyze their less-popular cousins, all still deserving of fame and acclaim.

- “Never Before Has Such a Terror Appeared”: Viking Raids into Ireland – Part I

- Burning, Pillaging, and Carving up the Lands: Viking Raids into England - Part II

Rorik of Dorestad: The Canny Diplomat

Appearing on the pages of continental chronicles in the 840s, an individual named Rorik from Denmark wanders into the frame as a masterful tactician and politician, the likes of which we see today in the world’s most astute diplomats and public speakers. To dissuade further Viking raids against the Low Countries (which were at the time under the hegemony of the Frankish kings), Rorik was appointed as a defender of Dorestad, a trading emporium underlying today’s Wijk bij Duurstedde, in The Netherlands. Paid presumably with a bribe and a promise of landed wealth, Rorik was entrusted to safeguard the shores from his own kinsmen, to act as an ‘anti-Viking’, by using his fleet and his forces to divert other Viking crews from attacking the Low Countries. That is, more or less, what happened, though not exactly without error.

You will have all heard of Rollo, the enterprising raider who was given land in France in 911, which would later become the Duchy of Normandy. Rollo was following a road well-trodden, laid by the likes of Rorik and his 9th century forebears. Between 836 and 840, Dorestad was ‘burned to the ground’ and ‘absolutely destroyed’ about three or four times, and only then was it given to Rorik as a benefice. Reading between the lines of these Frankish annals, we can see that the place clearly wasn’t destroyed and then rebuilt every few months; we must then question what exactly the annalists were getting at! Were they alluding to a Scandinavian takeover of the place, and were they reticent to acknowledge its status as newly owned by their enemies? By ‘giving’ Dorestad to Rorik, Frankish kings may have just been officializing an already lost piece of territory, one that persisted as a cap in Rorik’s feather for a further thirty years before his death.

During his reign over Dorestad, Rorik fulfilled his promise of diverting further Viking raids, but only in the most literal sense. By dissuading raiders from attacking Dorestad and its hinterlands, Rorik effectively just redirected Viking crews elsewhere in the Frankish kingdom, leading to them becoming a problem for other kings. He did not solve the problem but delegated it to someone else, as politicians often do. In this regard, over his thirty-year career, Rorik of Dorestad deftly played the courts and chronicles of 9th century France, achieving status, land, and wealth within a Frankish and Frisian sphere, despite being cut from the same cloth of enterprising raider as those he was paid to repel!

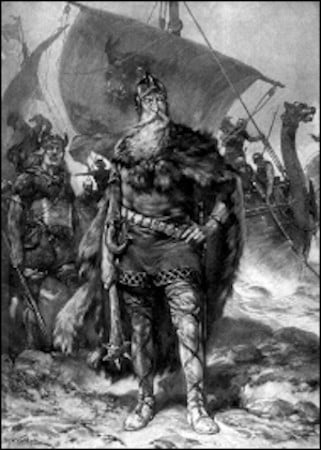

Rorik of Dorestad remembered as a powerful high-ranking ruler in 1912 by Dutch artist H. W. Koekkoek.

Knutr & Sigfrodr: Coin Kings of York

Rorik is relatively well documented in major continental annals, so his ‘D-lister’ status largely comes from the fact he paved the way for other more famous figures like the aforementioned Rollo. Near-contemporary rulers across the North Sea are even more obscure, Knutr and Sigfrodr who ruled over York between 895 and 905. Unlike Rorik, these two aren’t even afforded a few scraps of ink and parchment, and our knowledge of them comes only from a few coins minted in the city bearing their names. We do not know what they were like as rulers, or who they were allied with, their policies and so on, but we can infer certain details based on the careful study of their numismatics. Knutr’s coins, for one, which render his name as CNVT, are laid out in the format of the Christian cross, and to spell his name one must make the sign. In rendering his name this way, either King Knutr or his moneyers were demonstrating a somewhat advanced knowledge of contemporary theology, recognizing that money and the institution of the church were linked; to ratify the rule of the king in York, associations with God and the church were vital. So, while we do not know much about Knutr himself we can infer that his reign must have been religiously tolerant, and perhaps he was even a Christian.

As for Sigfrodr, he preceded Knutr and likely ruled at the same time as a co-king if certain coins from the Cuerdale Hoard, Lancashire, are anything to go by. Contained within this immense silver hoard were a few coins which display both rulers’ names, suggesting there may have been a brief period when both monarchs were active within the city. Did they get on? Or was it a case of an overking-and-client relationship, as has been suggested between Alfred the Great and Ceolwulf II of Mercia? Whatever the case, both Sigfrodr and Knutr defy certain identification, though many have tried to correlate them with other similarly named individuals on either side of the Irish Sea. One ‘Sichfrith’ is mentioned in the Chronicon Aethelwardi at the same time as Sigfrodr was branding coins with his name, and someone called Cnut appears in later Icelandic sagas, placed vaguely in Northumbria.

A third ‘coin king’, Airedeconut, is known from another Lancashire hoard found in Silverdale, and he is a Z-lister compared to these two. He may have ruled different parts of Northumbria at the same time as Knutr and Sigfrodr, the trio positioned as quarrelsome vultures squabbling over the remains of the former kingdom.

An example coin of Knutr of York (895-905); image courtesy of © Fritz Rudolf Künker GmbH & Co. KG, Osnabrück and Lübke & Wiedemann KG, Leonberg

- Traces Of Viking Ivar the Boneless’ Dynasty At Waterford, Ireland

- Dead Viking Dynasty Invade Scottish Neolithic Tombs

Sitriuc Silkbeard: Ireland’s Ally or Enemy?

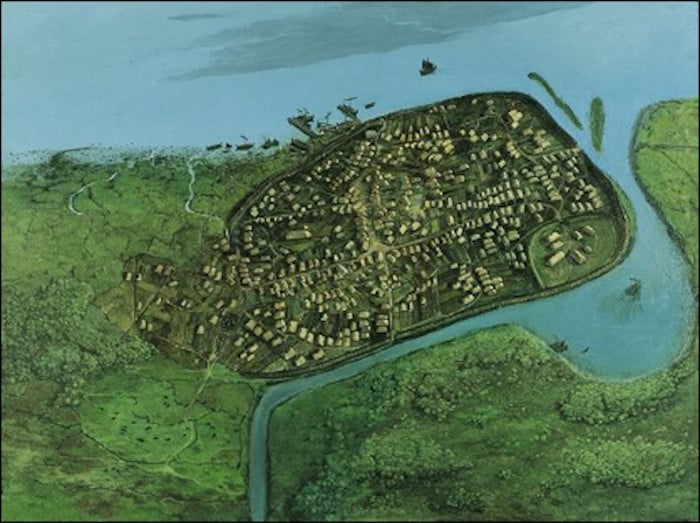

Moving forward about a hundred years, our attention turns to Dublin, and its important role as a contested entrepot of the Irish Sea. From Dublin, slaves and fine goods were processed and exported to as far away as Iceland and Constantinople, and such activities made the city rich. Since its foundation in the 9th century, Dublin had been juggled between Scandinavian and Irish overlords, and by the end of the 10th, was a golden prize between competing kings Mael Sechnaill and Brian Boru. Sandwiched between these two Irish overkings, however, was the local ruler Sitriuc Silkbeard.

Sitriuc is a prominent antagonist in the pseudo-historical War of the Irish against the Foreigners, in which he is positioned as Brian Boru’s bane, a whelp who keeps getting back up after being put down. After conquering Dublin sometime in the 980s, Sitriuc frequently fought against or worked with competitors of both Scandinavian and Irish stock, allegedly including the famous Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvasson. If you were to time-travel back to tenth-century Dublin and fast-forward through a couple of decades, you might see a different ruler in the city each year; such was the fractious nature of the place. Nevertheless, Sitriuc is immortalized in various apocryphal foundational tales as a major player, but he is remembered for reasons perhaps antithetical to his actual presence. Hundreds of coins minted during and after his reign, and the general persistent status of Dublin as a wealthy town point to his effective rulership, and despite being put under the boot of various other over-kings (like Brian Boru, who conquered Dublin in 1000), Sitriuc remained ever-present. No doubt he was disliked as much as he was needed. Sources depict him on various occasions being expelled from the city, then returning to apologize and prostrate himself in servitude; this was a canny, if perhaps shameless politician working his hardest to keep a white-knuckle grip on power and wealth. A fragmentary thirteenth-century poem in praise of Sitriuc remarks how bustling and thriving Dublin became under his watchful eye, and this urban activity is not merely limited to the page: excavations across the city have more than demonstrated the city’s wealth and long-distance links.

Whether he was a foe or friend to Dublin and Ireland, Sitriuc often ended up playing both sides so that he always came out on top; when Brian was alive, he was his dutiful servant, and technically also a son-in-law; then Sitriuc betrayed him in favor of Mael Sechnaill; when he died, Sitriuc knew he could find an ally in Cnut the Great, and so and so on this process continued until he abdicated the throne of Dublin and went to die as a monk.

A reconstruction of Viking Age Dublin in the year 1000, when Sitriuc Silkbeard sat somewhere between independent and underling of Brian Boru, his nominal overlord. Image courtesy of © The National Museum of Ireland.