Ancient Historians and Their Tales of Bizarre Tribes

Ancient Greek and Roman historians captivated their audiences with accounts of bizarre tribes dwelling on the periphery of the known world. Their customs were odd and their appearances even more fantastical. They represented the ever-present fascination with the world and its wonders. Historians like Herodotus, the Father of History, Diodorus Siculus, Pausanias, Philostratus, and Ctesias infused their narratives with observations and sensational stories, contributing to a mythic portrayal of distant lands. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder compiled an impressive array of information on numerous exotic tribes, making him the primary source for much of what was known and further inspiring those who came after him. His work would flourish through the Middle Ages, giving new meaning to the unknown and enigmatic. With all the marvelous, imaginative, and fanciful depictions of curious tribes passed down through time, what better place to start than the beginning.

Hairy Men and Dog-Headed Hunters

The Atlas Mountains of Libya had long been a place of obscurity to the ancients; many awe-inspiring myths and tales originated from this rugged landscape. Venturing travelers often spoke about the strange tribes of people that roamed these rolling hills. Most, coincidentally, shared a likeness in appearance to Pan, god of the wild, or the satyr, mischievous and covered in hair. The Satyros Libys and the Aigipan Libys were feral, uninhibited men supposedly encountered by the wise, miracle worker Apollonius of Tyana and recorded by Pliny the Elder. To the west, along the Ethiopian Nile, Philostratus documented yet another of Apollonius’s adventurous trials with these strange men.

- Seeking The Ten Lost Tribes Of Israel, Finding DNA

- The Machlyes and Auses: Fierce Female Tribes of Ancient Libya, North Africa

While traveling through a small Ethiopian village, Apollonius and his companions were startled by the villagers' sudden uproar as they joined to pursue a reckless Phasma Satyros—a phantom satyr that had been terrorizing them for over ten months. He was incessantly mad for the women, having already killed two. Apollonius reassured his frightened companions and the villagers, revealing a plan to handle the satyr based on an old story about King Midas. The king had the blood of the satyr, evident in the shape of his ears. Based on advice once given by Midas’ mother on subduing a satyr, Apollonius mixed wine with water and poured it into the village’s cattle trough to intoxicate it. Following this plan, the phantom satyr drank the wine, falling asleep in a nearby cave. Later, as the group found him sleeping, Apollonius instructed the villagers to never harm the satyr; he was no longer a threat to them.

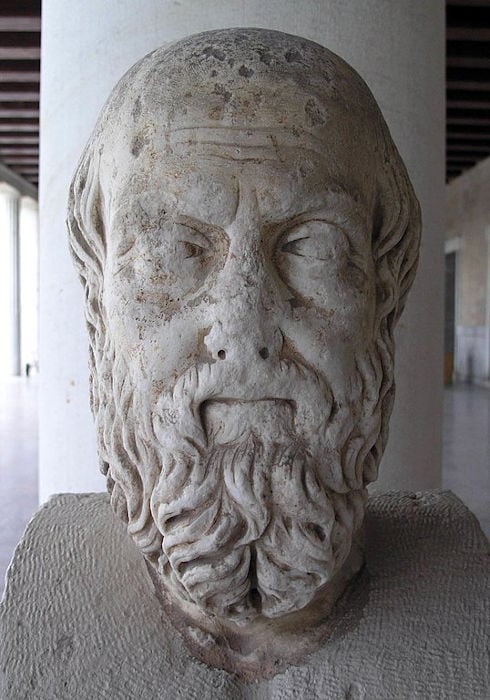

2nd century AD Roman copy of a bust of Herodotus. (GNU FDL 1.2)

Off the Atlantic coast of Africa were a peculiar group of islands referred to as the Satyrides. It was here that Pausanias, in his quest to better understand the fabled Satyros or Satyroi Nesioi of the islands, recounted the travelers Euphemos the Carian’s compelling story. On a voyage to Italy, the pair were driven off course by strong winds, coincidentally stumbling upon the island chain. On some of these islands were red-haired, horse-tailed Satyroi men. As Euphemos’s ship approached, fellow sailors, who had previous experience with the tribe, advised the captain of imminent danger. Dismissing caution, Euphemos began to dock just as the Satyroi hastily flung themselves onto the ship, attacking several women in the process. Fearing for their safety, the sailors abandoned a foreign woman on the island, where she was subjected to violating, brutal treatment by the inhabitants.

Similar to Pausanias, Pliny described a race of womenfolk located along the same waters. The islands Gorgades, possibly the Canary Islands, were a two-day sail from the African mainland. Carthaginian general Hanno visited these islands, describing the female population, the Gorgades, as being entirely covered in hair, while the men were extremely swift, inevitably escaping the general’s attempts at capture. Hanno, after seizing and slaying two female natives, presented the skins in the Temple of Juno in Carthage as evidence of his voyage. He claimed the skins remained on display until they inexplicably vanished around the time that Carthage was taken over by Rome.

Numerous ancient historians, such as Pliny, Hesiod, Herodotus, and Aelian chronicled a tribe of people west of Lake Triton who lived among snakes, beasts, and elephants called the Kynokephaloi, dog-faces. Aelian recounted them as having black skin, dog-like heads and teeth, and a body covered in hair. They lived by hunting gazelles and antelopes, and although they did not speak, they produced a high-pitched squeal. They also were said to have beards similar to that of serpents and possess impressively sharp, elongated nails. Notably quick on their feet and adept at navigating inaccessible regions, their elusive nature made them difficult to capture. Additionally, Aelian argued that they exhibited purposeful action, capable of stripping and cleaning shelled foods like almonds and nuts, understanding that the contents were edible while discarding the shells. They consumed wine and well-seasoned meat, showing partiality to carefully prepared food. Taking care of their garments and suckling milk from a woman's breast when young, they appeared to demonstrate a range of behaviors that blended human-like traits with their canine appearance.

The Kynokephaloi were supposedly spotted in India as well, as the historian Ctesias provided a detailed and vivid narrative. Nestled in the mountains of India, residing in remote caves, lived these dog-headed hunters and warriors. They understood the Indian language well, but preferred to communicate through barks or signing with their hands rather than articulated speech. Having a plentiful diet, they lived on raw meats, sheep’s milk, and the sweet fruit that hung from the many indigenous trees. Their society, characterized by longevity and cooperation, had no formal housing, instead, they slept on leaves, their clothes made from tanned skin or linen for the prestigious, and wealth was measured by the number of sheep one owned. Commonly, they would engage in trade with the Indian king, exchanging goods like amber and purple dye for resources and weaponry. In battle, they were steadfast and resilient, wielding bows and spears, making them virtually invincible.

Chest-Faces, Tiny People, Giant Feet, and Other Remarkable Tribes

Perhaps the most unusual tribe, and one that stood the test of time throughout Africa, India, Asia, and Europe were the chest-eyed Blemmyes or Akephaloi. Headless in nature, their faces rested upon their enormous chests, or in some cases, their bulky shoulders. They appeared in the Indian epic Ramayana in the singular form as a demon cursed to remain as a chest-faced, lengthy-armed monstrosity until being released. They were also mentioned in Asian folklore as a tribal community and by a Persian geographer alleging that they inhabited the island of Jaba off the coast of Indonesia. Herodotus and Pliny, on the other hand, placed them in the same region as the Kynokephaloi in Libya, nearing the sea coast of Africa. Though their culture was relatively obscure, they continued to be a profound topic of curiosity and legend beyond the Middle Ages.