The Role of Disease in the Decline of Great Empires

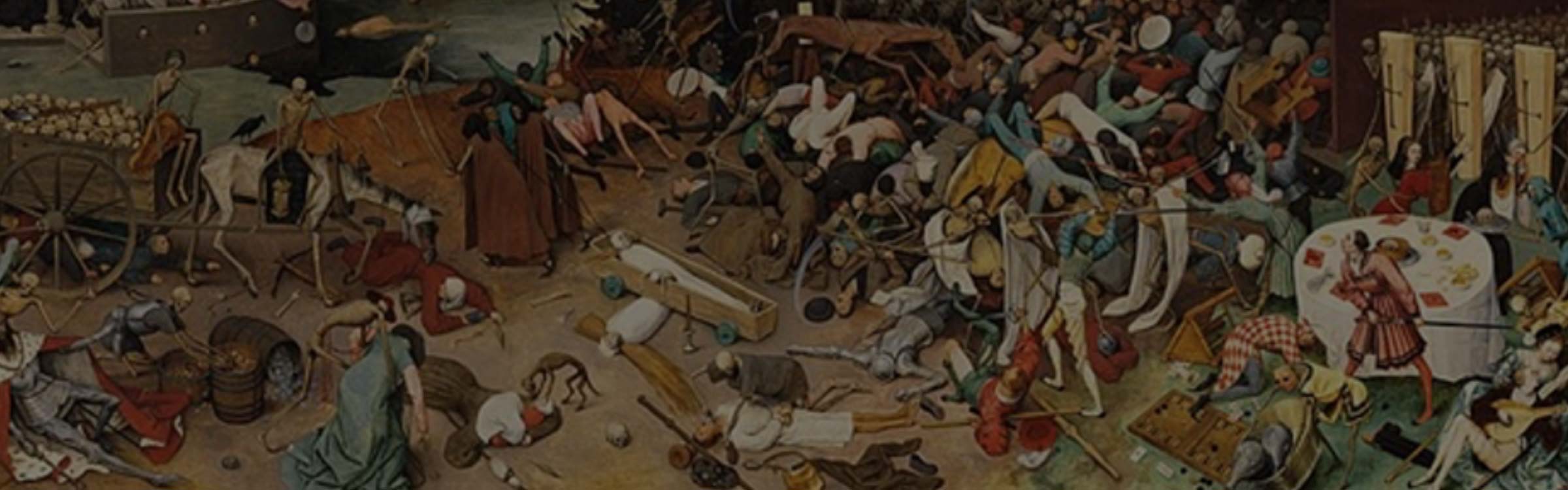

During their heights, many great empires were considered invincible - before God and Man. Ruling over great territories and thriving for centuries, such empires were major global powers, and invading them was never an option for a would-be enemy. And yet, even such great powers declined and crumbled, and often without the aid of an enemy. Because even the greatest of realms are helpless in the face of the invisible enemy - disease. In our distant past, when medicine was still in its infancy, disease and sickness was often rampant. And once it took hold, it spared no one and nothing that stood in its path. Empires included.

Disease, the Greatest of Conquerors

In ancient times, disease played a major role in the gradual decline of kingdoms, cities, and even vast empires. This is because major outbreaks of sickness further exacerbated the existing economic, social, and political issues. Of course, for most of history the causes for decline in power were usually warfare, repeated economic stress, and political instability. But often, such problems could have been dealt with, and power regained. With disease, however, there was no going back. Because disease decimated the population of an empire, strained its resources, and devastated the pre-existing social order. And without the people to put things right, how could an empire regain its power?

- Unpacking the Ten Plagues of Egypt: A Scientific Explanation

- A Crumbling Roman Empire: Treachery, Mutiny And Plague 250 – 270 AD

The biggest problem, arguably, was the loss of populace. As disease runs amok, it takes everyone who stands in its path, be it a commoner or a noble. And the population loss brings with itself the “dominoes” effect - things just start crumbling. With no people to farm and cultivate crops, to raise buildings and participate in public work, or even to rule a nation, things just spiral downwards. Food production is reduced and economic output drops. All this leads to widespread famine, further loss of life, inflation, economic stagnation, and a great strain on infrastructure. Needless to say, this also makes an empire vulnerable to attacks from its enemies. Like vultures circling a wounded prey, these enemies would descend upon an empire decimated by disease and deliver the final blow.

St Sebastian pleading for the life of a gravedigger afflicted with plague during the 7th-century Plague of Pavia by Josse Lieferinxe between 1497-1499. (Public Domain)

In many ways, disease was the greatest enemy an empire could have. It simply decimated the populace - something that had incredibly far-reaching consequences. Loss of people reflected on the military, the working class, the ruling class, the religion, the leadership - everything. And this is why disease has often been called the “shadow enemy” of great powers. It came as a hidden force that would decisively destroy a major power, even if it was old and vast beyond measure.

The Unstoppable Spread of Plague

Throughout history, there were several major global powers that found themselves at the mercy of unstoppable and all-conquering sickness. The first and foremost of these was the Roman Empire. Between 165 and 180 AD, it was utterly devastated by the Antonine Plague, which scholars believe was either smallpox or measles. First originating amongst the soldiers who were besieging the Mesopotamian city of Seleucia on the Tigris, it rapidly spread throughout the entire Roman Empire. It raged on through the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and claimed the life of roughly 10 million people, including the co-emperor, Lucius Verus. The total death toll equated to roughly 10% of the entire population of the empire, and it decimated many large cities at the time.

The plague returned just nine years later, and inflicted further loss of life, claiming up to 2000 lives per day just in the city of Rome. This resulted in a very difficult period for the empire, as the severe manpower shortages were reflected on both the military and agricultural sectors. Several centuries later, during the time of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), the Plague of Justinian broke out, raging between 541 and 542 AD. This was a devastating Bubonic Plague outbreak that claimed between 15 and 100 million lives. At the height of the outbreak even the Emperor Justinian I contracted the plague, but miraculously managed to recover. Either way, the empire survived, but never fully recovered - the plague hastened the fragmentation of its territories and the weakening of its once-great power.

An Instrument of Conquest

Could the plague have been used as a weapon of mass destruction? History tells us that yes, it could. Inadvertently, the Spanish Conquistadors hastened the downfall of the Aztec Empire by unleashing a devastating epidemic of smallpox upon them between 1519 and 1521 AD. When Hernán Cortés and his Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas, they unknowingly brought with them European diseases, particularly smallpox. Often coming into contact with Europeans for the first time, these ancient Mesoamericans had no immunity against diseases that were common in Europe. As a result, smallpox spread rapidly amongst the population of the vast Aztec Empire. It claimed millions of lives in a very short time, including the ruler, Cuitláhuac, and immensely weakened the empire and its ability to deal with the Spanish conquerors. All of this greatly contributed to the empire’s eventual fall to the Spanish in 1521 AD.

Similar to the Aztecs, the vast and powerful Inca Empire was utterly devastated by the introduction of smallpox, brought to the Americas by waves of European explorers. The disease killed the Inca emperor, Huayna Capac, and a significant portion of the population. This led to a civil war between Huayna Capac’s sons over succession, which weakened the empire internally. When Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish arrived, the Incas were already vulnerable due to this political and demographic collapse, facilitating the Spanish conquest. The Inca’s downfall is a key example of how disease destroys an empire on so many levels - economically, militarily, territorially, and politically.