The Egyptian Judicial System: Robust Pillar of Empire

Down the millennia, right from the hoary Narmer Palette to the grand reliefs on the walls of the magnificent temples of Ramesses II and that of later rulers; Egyptian artistic canon depicted the classic and symbolic ‘smiting’ pose in which the pharaoh was shown striking fear and awe in the hearts and minds of terrified enemies. It was, after all, the king’s bounden duty to eliminate the crippling and fearsome forces of chaos (Isfet) and maintain justice and order (Ma’at). And so, in the daily functioning of the State, stringent and unsparing action against anyone who fell afoul of the law was an integral part of the ancient Egyptian judicial system.

Wall relief of Maat in the eastern upstairs part of the temple of Edfu, Egypt. Ma’at was associated with justice and the law in ancient Egypt. (Rémih/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Eyebrows weren't raised when corporal punishment was mentioned; for people were accustomed to it from childhood. Scribe Amenemope certainly followed this course in letter and spirit when dealing with his young charges; for he states matter-of-factly: "A boy's ears are upon his back. He only listens when he is being beaten." As with the multitude of gods who judged the souls of the dead rigorously in the Hereafter, the Egyptians were merciless in dealing with criminals while they lived. In the adult world, depending on the gravity of the crime one committed: impalement, drowning, decapitation, burning, or being thrown to crocodiles—were some of the brutal ways in which one could breathe his or her last.

But, to be sentenced to heavy labor was akin to a living death, as the unfortunate person could wind up working for several years in gold or turquoise mines abroad under the harshest, most pitiless conditions imaginable – many never made it back home alive. Exile was the prescribed form of punishment for grave crimes. Few examples of royal clemency from the early periods of Egyptian history survive. The evidence at hand mostly comprises literary works – like ‘The Story of Sinuhe’ that is set in the aftermath of the death of Pharaoh Amenemhat I, founder of the 12th dynasty. The protagonist, Sinuhe, received a pardon from the pharaoh which paved the way for his return from exile.

Essential Law Enforcement

Exacting local officials and the Argus-eyed police force ensured the observance of law, prevention of criminal activities, and the swift apprehension of wrongdoers. These authorities followed several protocols in their efforts to solve crimes, much as is done in our day and age. Some of the investigative approaches included gathering circumstantial evidence, clues against suspects, reviewing public records and using physical coercion whenever it was deemed necessary. The objective was to ascertain the truth; but if that failed, at least a confession was a real possibility. Often, the witness or defendant was subjected to a round of beatings before the administration of an oath; and a stele in the British Museum hints that this treatment worked rather effectively: "I am a man who swore falsely by Ptah, Lord of truth, and he caused (me) to behold darkness by day."

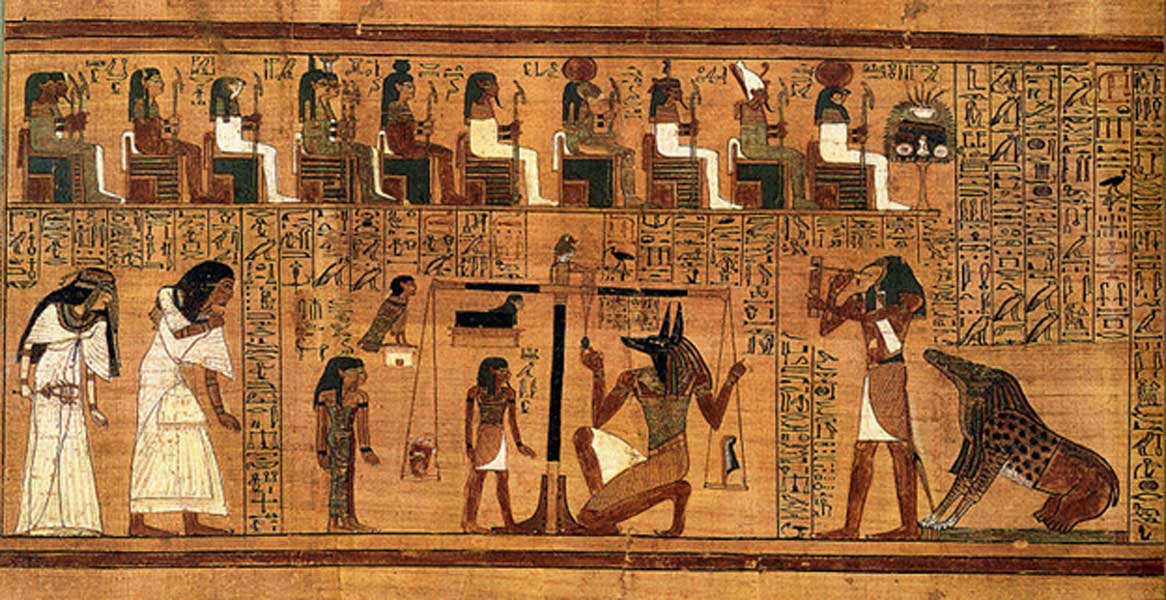

Excerpt from the ‘Book of the Dead’, written on papyrus and showing the "Weighing of the Heart" using the feather of Maat as the measure for the counter-balance. Created by an unknown artist C.1300 BC (Public Domain)

Dispensing severe forms of punishment rested solely on the pharaoh or the Vizier (prime minister), who exercised certain powers on his behalf. One account relates to how King Khufu heard of a magician named Djedi, whose specialty it was to rejoin decapitated heads. The Westcar Papyrus reveals that the monarch declared: “Let a criminal who is in gaol be brought to me and his sentence be executed!” If Djedi failed to prove himself, the condemned man’s eventual sentence would be fulfilled, albeit much ahead of time. But the opposite was also true, for the prisoner would receive his life back if Djedi succeeded.

- The Truth About Lie Detection in Ancient and Modern Times

- The Bizarre Importance of Bleeding Bodies in Medieval Trials

- Trial by Ordeal: A Life or Death Method of Judgement

- Prisons and Imprisonment in the Ancient World: Punishments Used to Maintain Public Order

An ill-fated person convicted of a serious crime faced the ghastly prospect of impalement on a sharpened spike, in the outskirts of the city. This excruciating and extreme form of state-sponsored execution meant that the deceased would have no chance to be mummified and placed in a tomb, per religious requirements – which destroyed any hope of an Afterlife. And worse of all, there would be no one left to speak his name! Individuals of high rank who were convicted had their names and inscriptions erased from their tombs; for there would be “no tomb for anyone who rebels against His Majesty, and his corpse shall be cast to the waters.”