“Lion of the North” Gustavus Adolphus and the Thirty Years’ War: Victories and Downfall – Part II

This is the recounting of the dramatic life of the “The Golden King” and “The Lion of the North” Gustav Adolf, and the Swedish Empire during stormaktstiden – “the Great Power era”.

As Gustav II Adolf (King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden) waited in Werben, Germany, Johann Tserclaes, the Count of Tilly (Field Marshall of the Catholic League’s forces) received a message from Field Marshall Pappenheim requesting that he come to Magdeburg and aid in its defense against the Swedes. After some time, Count Tilly decided to send three cavalry regiments on a recon mission towards Werben on July 27, 1631. After a few days, Gustav received word of the cavalry advance and quickly assembled 4,000 cavalry and led them towards the enemy force and surprised them at Burgstall and Angeren on August 1, 1631. The imperial forces suffered heavy casualties and lost their baggage.

![[Left] Engraving of Gustavus Adolphus (Public Domain) and [Right] portrait of Count Johann t'Serclaes von Tilly. (Public Domain)](https://members.ancient-origins.net//sites/default/files/Gustavus-Adolphus-and-Count-Johann.jpg)

[Left] Engraving of Gustavus Adolphus (Public Domain) and [Right] portrait of Count Johann t'Serclaes von Tilly. (Public Domain)

During this engagement, Gustav himself almost became a casualty. Those who were captured provided the Swedish king with valuable information. He soon learned that Tilly was planning to attack his forces at Werben.

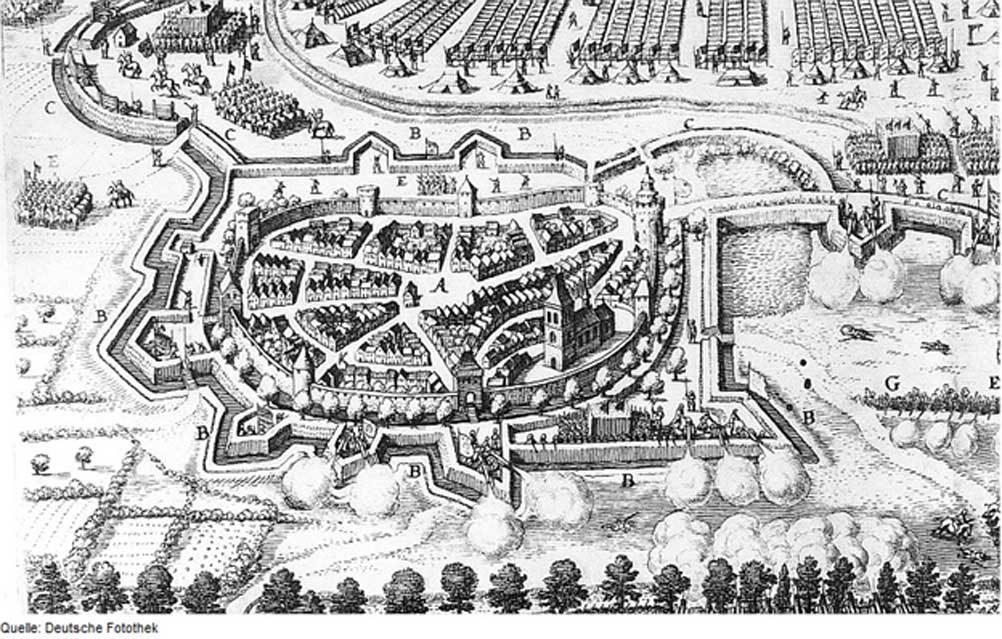

When news reached Tilly that the cavalry forces he had sent had been devastated, he fell into a rage. Tilly wasted no time; he mustered his forces, and pushed towards Werben with 15,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry. Tilly's hurry towards Werben was to prevent the Swedes from fully digging themselves into a defensive position. However, when Tilly arrived, he saw that Swedes had already set up defensive fortifications, for it was standard procedure among the Swedish military to do so once they set up camp. Tilly, seeing that the element of surprise was out of the question, positioned his forces and opened fire on the Swedish camp with sixteen heavy guns, and the Swedes obliged Tilly with a volley of their own.

Illustration of the Battle of Werben, detail.(Deutsche Fotothek/CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

The first day of fighting was primarily sorties and heavy skirmishing outside the Swedish perimeter. The second day was much the same, as each side exchanged cannon fire and engaged in limited skirmishes. While Tilly was poking and prodding the Swedes, he received intelligence that a German unit within the Swedish ranks would mutiny. Tilly, understandably suspicious of the information, decided that it was something he could not ignore. Therefore, Tilly gave the order to launch a full-scale assault on the Swedish entrenchments. This would be a grave mistake. As the imperial forces advanced, they came under a well-organized concentration of artillery and musket fire. The imperial forces began to drop quickly. Sensing that any further advancement would do them no good, they retreated, but as they did so, the Swedish cavalry fell on them. Six thousand imperial forces lay dead on the field of battle, while the remaining wounded and untouched scattered.