Lost History of a Mad Man? Revealing the Surprisingly Compassionate Side of Nero, One of the “Worst” Ancient Roman Emperors

For centuries, the Roman emperor Nero has been well chronicled for his cruelty. Stories about his madness include divorcing his first wife before having her beheaded and then bringing her head to Rome for his second wife, having his own mother executed, as well as castrating a former slave before marrying him.

However, despite the numerous charges against him by ancient writers, there are also evidence that Nero enjoyed some level of popular support. “He let slip no opportunity for acts of generosity and mercy, or even for displaying his affability,” wrote the otherwise critical Suetonius. More recently, a poem dated about two centuries after Nero’s death depicts him in an even more a positive light by proclaiming Nero a man “equal to the gods,” suggesting many individuals in the Roman Empire held a favorable view of him long after his death.

After Nero ordered his mother to be executed in 59 CE due to her interference in his personal life and political policies, he is widely portrayed a becoming more of a tyrant, spending excess amounts of government funds on personal indulgences.

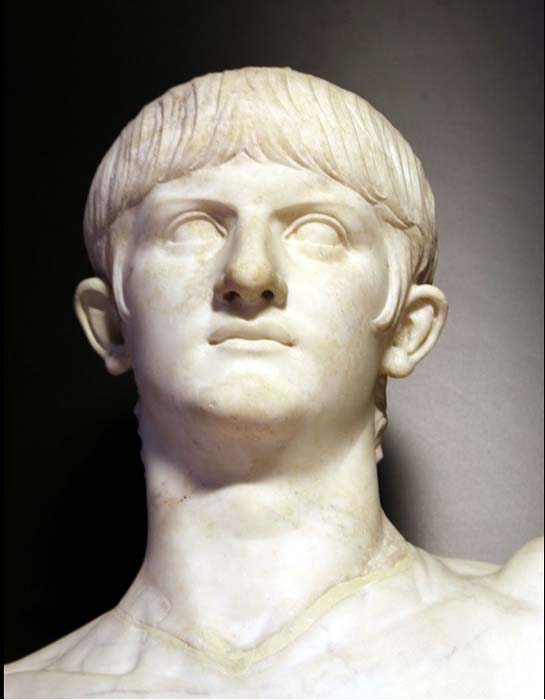

Marble busts of emperor Nero, circa 54/59 AD. (G.dallorto/Public Domain)

It was believed for a long time that Nero started the great fire in 64 CE to make room for his new villa. The impression one is left with from this story is that his mother, Julia Agrippina (Agrippina the Younger), may have been the only steadying influence he had. But is this true?

The Trouble with Nero: Love, Hate and Lost Histories

Nero’s history is problematic as there are no surviving contemporary historical sources. Although these first histories existed, they were described as overly biased: they were either too pro-Nero, overly critical of him or, worse, they contradicted each other regarding a number of events. Nevertheless, these lost primary sources formed the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Nero written by the next generations of historians. The bulk of what is known of Nero comes from Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio - all of whom wrote their histories on Nero 50 to 150 years after his death. Although they contradict each other on a number of events in Nero's life, they are consistent in their condemnation of Nero.

- Herodotus, Cato the Censor and Josephus: Understanding the Life and Times of Historians of the Ancient World

- Mythbusting Ancient Rome – Throwing Christians to the Lions

- Questioning the Dramatic Story of the Empress Messalina, Was She a Cruel Doxy or the Victim of a Smear Campaign?

- The Year of the Four Emperors

However, there are also sources that depict Nero in a more favorable light. Upon hearing the news of Nero’s death, Tacitus describes the lower-class, slaves, frequenters of the arena and the theater as being upset with the news. Eastern sources such as Philostratus II and Apollonus of Tyana mention that Nero's death was mourned as he had restored their liberties with wisdom and moderation, respecting them even as he was holding their liberties in his hand.

Living Under His Mother’s Shadow? The Rise of the Young Emperor

Nero’s mother, Julia Agrippina, had an eventful life. She was the great-granddaughter of Augustus through her mother, Vipsania Agrippina (Agrippina the Elder). Her father Germanicus, known as a great Roman general in his own right, was adopted by Tiberius. It was her brother, Gaius Caligula, who succeeded Tiberius in the end. Caligula was then succeeded by Claudius, her uncle. When Claudius’s wife, Messalina was executed for treason, it was not long before Claudius was changing the laws of incest so he could legally marry Julia Agrippina.