A Curious Case of Linen for Papyri—Lifting the Veil off the Lack of Written Materials in Tut's Tomb

The tomb of the last ruler of the Amarna bloodline, the boy-pharaoh Tutankhamun, yielded a wealth of anomalies: beginning with the tiny size of his burial place, the appropriation of funerary goods – a majority from a mysterious female predecessor, Neferneferuaten – the apparent haste with which his sepulcher was completed and filled with objects, and of course, the charred remains that hint at an unconventional or botched mummification. But an aspect that often fails to receive the attention it deserves is the lack of written material in KV62.

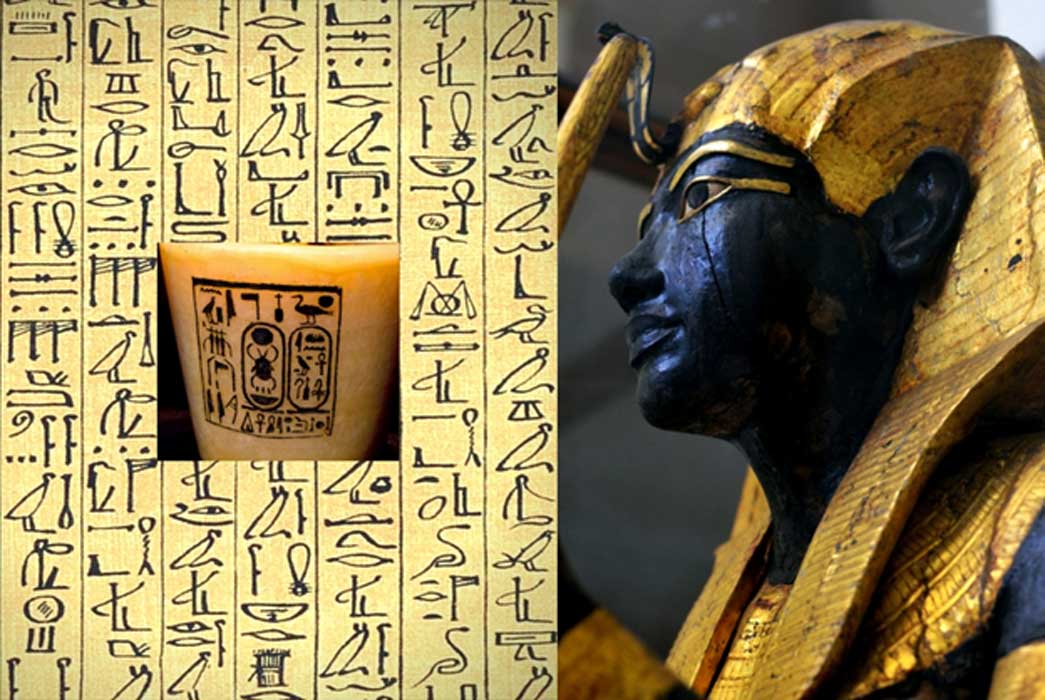

A sandstone portrait of King Tutankhamun wearing the khepresh or Blue (War) Crown. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The ancient Egyptians packed their tombs with everything the dead would need in the Afterlife. Along with food, clothing and furniture, funerary texts – such as a copy of the Book of the Dead – that served as a guide to combat challenges during the perilous journey through the Underworld, were mandatorily included with the deceased; at least, by citizens who could afford it. In this regard, even the sumptuously stocked non-royal tomb of the highly-respected Eighteenth Dynasty ‘Overseer of Works’ Kha who was buried with his wife Merit in Deir el-Medina, revealed a stunning array of grave goods and offered one of the earliest examples of the Egyptian Book of the Dead ever to be discovered.

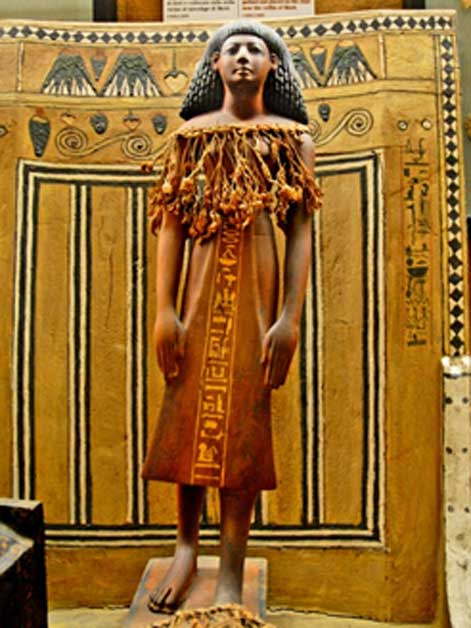

A statuette of the Eighteenth Dynasty official, Kha, from Theban Tomb 8 in Upper Egypt. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. (CC BY 2.0)

Kha was obviously a man who was much in demand for his exceptional skills as an architect. A court favorite, he served under three consecutive pharaohs and held the unique distinction of having designed and supervised the construction of three royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings; those of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. Designated TT8, Kha’s tomb was discovered intact in 1906 and excavated by Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli and Arthur Weigall, the British Antiquities Services Inspector.

Detail of the stunning facemask of the inner coffin of Kha who was the ‘Overseer of Works’ under three consecutive rulers. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy.

DAY OF DAYS

When British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun on 4 November, 1922 he proclaimed that it was, “the day of days, the most wonderful that I have ever lived through, and certainly one whose like I can never hope to see again”. It was indeed a momentous occasion, and the atmosphere soon turned electric as news of the find – initially designated Tomb 433 in Carter’s sequence of discoveries – spread across the world. KV62, that had lain hidden below the huts of workmen who constructed the tomb of Ramesses VI, succeeded in delivering a much-needed shot in the arm for Egyptology, considering, Theodore Davis like Belzoni before him had fervently believed that the Valley had been picked clean.