Magic Armor Can’t Save the Tragic Heroes: Duty & Doom for Karna, Ferdiad & Achilles

It is no longer a secret that there are historical connections between the myths from everywhere in the world, indicating that every culture had strong influences on each other and their legends. A minor example of this can be seen in something as simple as a body armor - Ancient India’s Karna's kawach (“armor”) has been compared with that of Ancient Greek’s Achilles’ Styx-coated body and with Ancient Irish warrior Ferdiad’s horny skin that could not be pierced.

Back in the eight and the ninth centuries BCE, Greece and India had established universities where a variety of subjects were taught and learned, including literature and rhetoric. Greece and India are also homes to the two greatest surviving epics - the Iliad and the Mahabharata. Another epic, Táin Bó Cúailnge (commonly known as “The Cattle Raid of Cooley”), a legendary tale from early Irish literature, followed some centuries after as it may have been put to writing in the eighth century CE. However, it had a considerable oral history before any of it was committed to writing.

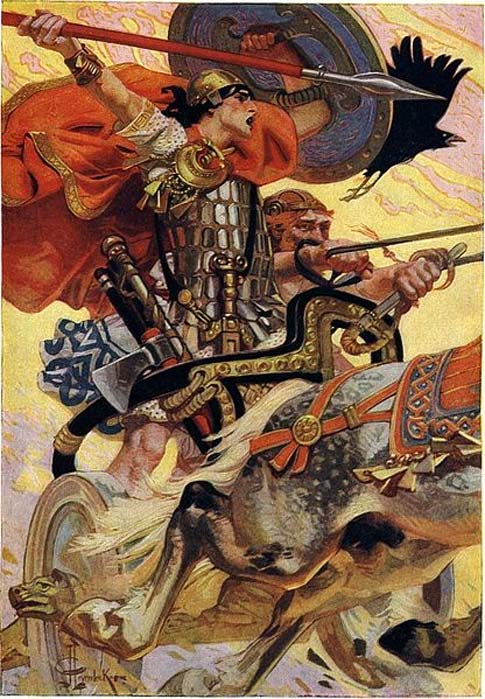

Cú Chulainn is the central character of the Ulster (Ulaid) cycle in the in medieval Irish mythology and literature. (Public Domain)

A surviving example is the poem Conailla Medb michuru ("Medb enjoined illegal contracts") by Luccreth moccu Chiara, and dated around 600 CE, tells the story of Fergus' exile with Ailill and Medb (the poet describes this event as sen-eolas ("old knowledge"). Two seventh-century poems also allude to elements of the story) in Verba Scáthaige ("Words of Scáthach"), Scáthach prophesies Cú Chulainn's combats, and Ro-mbáe laithi rordu rind ("We had a great day of plying spear-points") refers to Cú Chulainn’s boyhood incident that formed a section of the epic.

The Tragic Heroes Suffer

However, it was the three tragic figures who seemed to highlight the similarities of these epics. In Poetics, Aristotle defines a tragic hero as “a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty.” Aristotle further describes a tragic hero as a man who suffers more than what he deserves as, from the beginning of the story, he is doomed without being the one responsible for the flaw he possesses. The nature of the tragic hero is noble but, at the same time, imperfect—allowing the audience to sympathize with him, perhaps even more so than the main character of the story.

Karna from Mahabharata, Achilles from Iliad, and Ferdiad from Táin Bó Cúailnge aptly fit Aristotle’s definition of a tragic hero. By the standards of their individual cultures, the three heroes are somewhat marginalized from society and definitely suffered much more than what they deserved. None of them is the main character of their epics. However, through their individual stories, they also arouse fear and empathy in their audience while they learn from their experiences, making them become most humane characters in their stories.

The Great Wars in the Illiad, Mahabharata and Táin Bó Cúailnge

The three epics were separated by centuries and great distances. However, their story is the same: a great war and the emergence of a new age. The Mahabharata is the story of the great battle that was fought on the field of Kurukshetra between the five sons of King Pandu and their allies on the one side and the hundred sons of King Dhritarashtra with their allies on the other side. The battle involved virtually every tribal king and every powerful city-state in Central and Northern India at the time and was the culmination of a long history of struggle and diplomatic maneuvering.

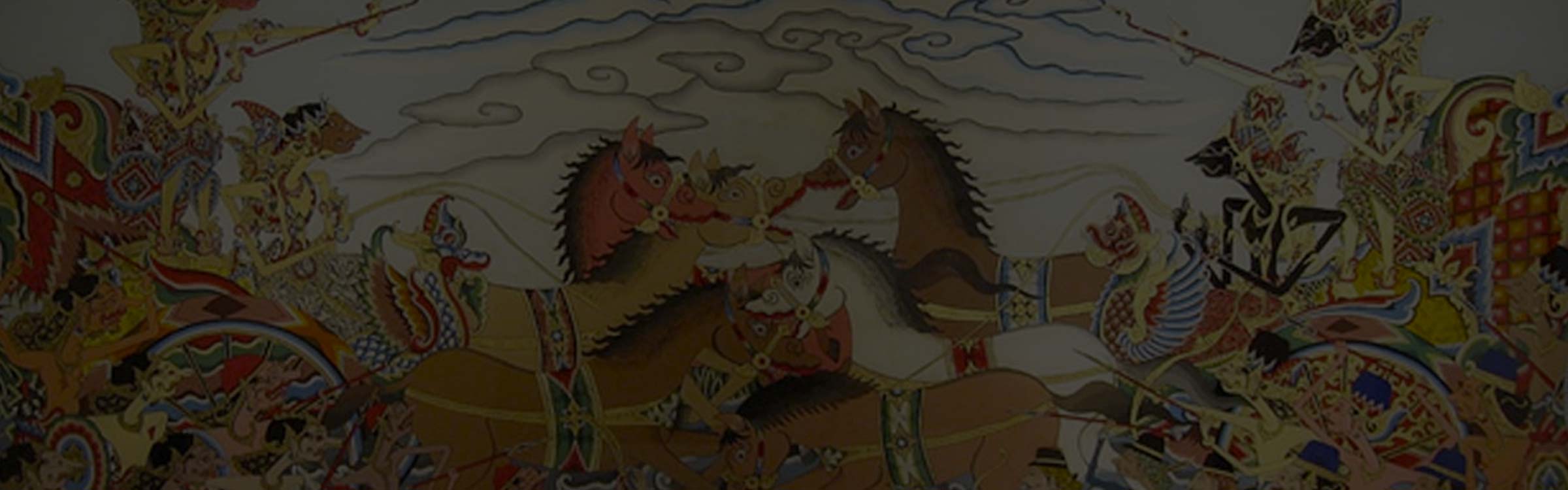

The Cirebon glass painting of Bharatayudha battle in Wayang style. Kurawa on the left and Pandava on the right. On the left Karna rides the chariot with Salya as the driver, while on the right Arjuna rides the chariot with Kresna as the driver. (Gunawan Kartapranata/CC BY-SA 3.0)