Nefertiti and the Perfect Serenity of Death: Mesmeric Shabtis of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun —Part II

Archeological records and a trove of recovered specimens inform us that shabtis (funerary figurines) produced from different materials were placed in the tombs of Eighteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun, his father and grandfather. The exquisite workmanship of these funerary objects aside, did KV62 yield figurines that were originally destined for the burial of a female pharaoh—and was this person Nefertiti?

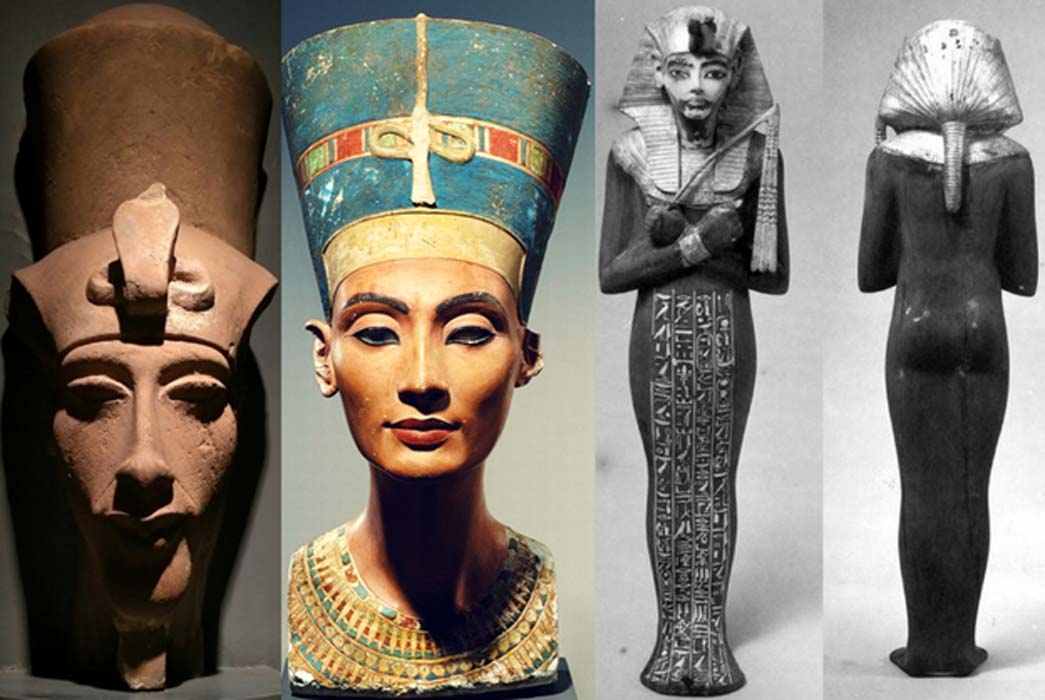

Ancient Egyptian burials consisted of anywhere between two, and, in pharaonic tombs, around a thousand shabtis. It was believed that these “Answerers” would carry out tasks on behalf of the deceased in the Hereafter. A superb display of exquisite figurines from different periods, produced from various materials. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

The Finer Specimens

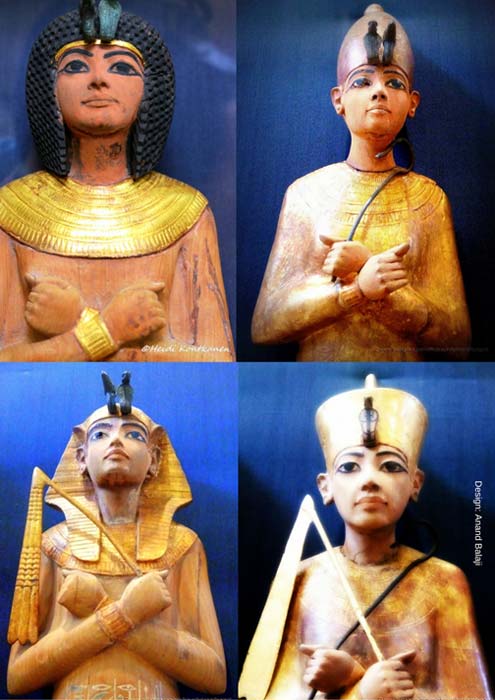

Given the virtual surfeit of shabti figurines, Howard Carter—the discoverer of the magnificent tomb of Tutankhamun—and his team were awestruck at the sheer beauty of the collection; especially the elegance of the six larger wooden objects. The British archeologist noted, “In the finer specimens, by their own symbolism is expressed the perfect serenity of death.”

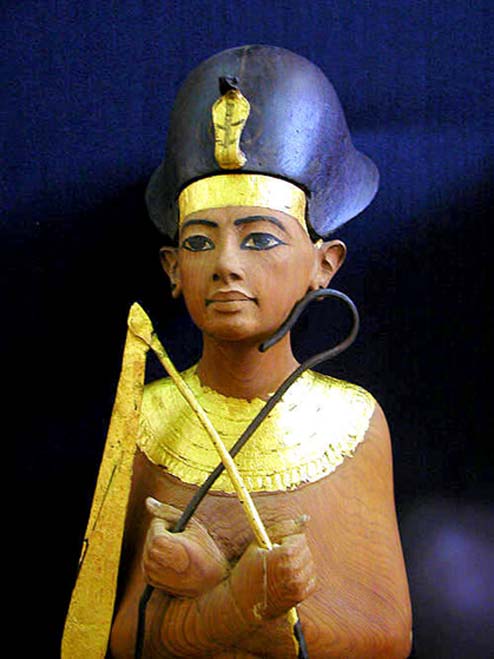

Some of the larger shabtis, such as this one wearing the Khepresh (Blue/War Crown, Obj. No. 318a), were donated to the burial of Tutankhamun by the mysterious military officer Nakhtmin whose name was inscribed on the base of the object. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. (Photo: Jon Bodsworth)

The boy-king’s burial seems to have received the pick of gorgeous figurines, to enable him to avoid physical labor of any kind in the Afterlife. Tutankhamun’s shabtis were produced in a range of materials including different types of hard and soft stones, such as quartzite and travertine or Egyptian alabaster. Also, cedar wood was used to make shabtis that were both fully and partially gilded. Last but not the least, Egyptian faience – a sintered-quartz ceramic displaying surface vitrification which creates a bright luster of various colors, with blue-green being the most common – that most popular of materials among shabti-makers, was no exception in Tutankhamun’s assemblage; the color varying from blue-green to deep indigo.

Howard Carter was highly impressed with the selection of large-sized shabtis in Tutankhamun’s sepulcher. Specimens wearing different headgear are shown here; and those with the tripartite wig (top left) were the most common. However, a few shabtis do not seem to have been destined for the boy-king. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. (Photos: Susan Ryan and Heidi Kontkanen)