Understanding the Monotheism of Akhenaten: Decay of a Dream and the Final Curtain Call–Part I

Pharaoh Akhenaten has been revered and reviled in equal measure for unleashing his religious policy of one god, the Aten sun disc. But, was the king a monotheist in letter and spirit – one who proscribed the worship of not merely the state god Amun, but all the deities in the Egyptian pantheon? Was he a benevolent poet and dreamer who set out to establish a Utopian city; or a ruthless tyrant who built his dreams over the dead bodies of countless subjects? Over and above all this, are we mistaken in our assessment of the monarch, as we view the man and his motivations through the prism of modernity?

Pharaoh Akhenaten blazed his own trail like none before him; but a proper understanding of the person behind the king eludes us. This colossal sandstone sculpture that shows him wearing the Khat headdress and double crown was discovered at Karnak Temple. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

New Life, New Hope

In 1798, one of ancient Egypt’s most controversial rulers, Neferkheperure-waenre Amenhotep (IV)-netjerheqawaset (Akhenaten), came to light after thousands of years, when savants of the Napoleonic expedition stumbled upon the ruins of Akhetaten, his short-lived capital city. The first observers were struck with immense awe, wonderment, and confusion—for they were the first people in millennia to view the grotesque and unconventional images of the king. With the subsequent decipherment of hieroglyphics, we believed that Akhenaten the person had finally emerged from the shadows – or is he yet to?

Much ink has been spilled in analyzing the probable motives behind Akhenaten’s abandonment of the royal capital Thebes in Regnal Year 5. Many theories have been proposed towards this end: the monarch’s revulsion of the growing power of the Amun priesthood; a true calling that led him out into the deserts of Middle Egypt to establish Akhetaten in honor of the solar deity, the Aten; the great desire to hearken back to Egypt’s religious roots; and, the more uncharitable assumption states that he built a new city because he was nothing more than an intolerant megalomaniac.

- Objects of Wonder: The Symbolism and Suspense behind Ancient Egyptian artifacts

- Pharaoh Akhenaten: A Different View of the Heretic King

- The Art of Amarna: Akhenaten and his life under the Sun

These traditionally held beliefs seem to be lacking in many respects. Therefore, a re-evaluation of the life and times of Akhenaten is the need of the hour. Doubtless, he charted his own course and introduced radical changes to religion, polity and art; but were these the real reasons why his contemporaries hastened to malign his memory – or was there something more sinister to this saga than at first meets the eye?

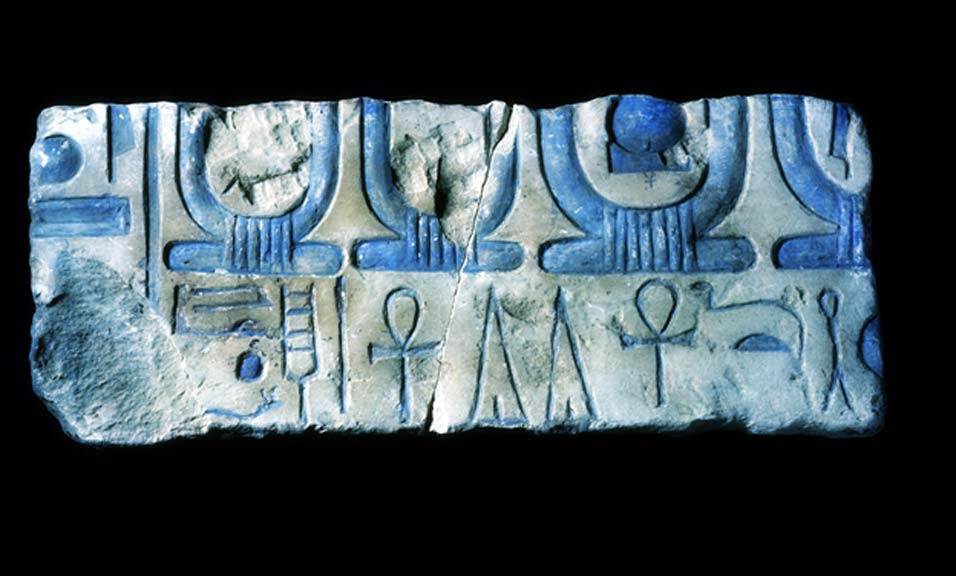

Painted limestone relief with cartouches of the Aten. Probably originally from Amarna (Akhetaten), but discovered at Hermopolis (Ashmunein). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Upon his arrival in Akhetaten (‘Horizon of the Aten’— modern Tell el-Amarna) riding his ‘great chariot of electrum’, Akhenaten erected a series of sixteen Boundary Stele to demarcate the sacred limits of the foundation. Amarna expert Barry Kemp explains, “Akhenaten never says he was going to build a city instead he refers to is as the ‘Aten’s piece of desert below the cliffs’.” On Boundary Stela K, dated to his Regnal Year 5, IV Peret, Day 13; the king revealed the reasons that impelled him to choose the desolate and forbidding site. This has been likened to the first ever service or mass that extolled the Atenist philosophy:

‘As the Aten is beheld, the Aten desires that there be made for him [...] as a monument with an eternal and everlasting name. Now, it is the Aten, my father, who advised me concerning it, [namely] Akhetaten. No official has ever advised me concerning it, not any of the people who are in the entire land has ever advised me concerning it, to suggest making Akhetaten in this distant place. It was the Aten, my fath[er, who advised me] concerning it, so that it might be made for Him as Akhetaten... Behold, it is Pharaoh who has discovered it: not being the property of a god, not being the property of a goddess, not being the property of a ruler, not being the property of a female ruler, not being the property of any people to lay claim to it.... I shall make Akhetaten for the Aten, my father, on the east of Akhetaten, the place which He Himself made to be enclosed for Him by the mountain...’

Become a member to read more OR login here