Did Pytheas, Ancient Navigator, Geographer and Astronomer Discover Mysterious Thule?

About 600 years BC, Greek merchants sailed west the length of the Mediterranean Sea and founded a city named Massilia. Now it's called Marseilles, France. The purpose of the new port was to control commerce by means of the Rhone river into the interior of western Europe. It would have been easier, of course, to conduct such trade by sailing through the Strait of Hercules, now called Gibraltar, and then up the Atlantic coast. But for at least 200 years the Carthaginians had been guarding the straits, sallying forth from their ports in north-Africa to enforce heavy tariffs and eliminate economic competition. They had grown rich in the process. All kinds of goods such as tin from Britain, gold from Ireland, amber from the Baltics, and ivory from a mysterious region in the north, were being exchanged for bronze tools and weapons, pottery, cloth and wine. Commerce was brisk the length of the inland sea, and there were riches to be made by those who could establish and hold important trade routes. Somewhere around 330 BC a navigator, geographer, and astronomer named Pytheas, who possessed a seemingly insatiable curiosity, decided to explore those trade routes for himself. He became the first literate, European-educated, man to do so.

The Rock of Gibraltar's North Front cliff face from Bayside (c.1810) showing the embrasures in the Rock. (Public Domain)

At least, that's what many modern scholars now believe. Pytheas wrote a book about his journey that he called On the Ocean. But no one alive today has ever read it. It disappeared long ago, and the only reason we know about its existence at all is that ancient writers quoted it from time to time, some in a derogatory fashion. What became of it, no one knows. But it's entirely possible that such a ground-breaking volume would have found a home in the Alexandrian Library, named after the world's most famous Greek and dedicated to collecting all the world's wisdom. If so, it would probably have burned in the one of the great fires that destroyed so much of the so-called ‘pagan’ knowledge of that day.

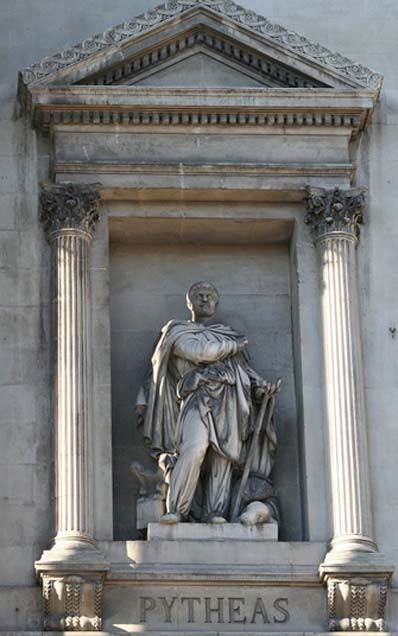

Statue of Pytheas outside the Palais de la Bourse, Marseilles. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Emerging from the Realm of Mythology

Recently the legend of Pytheas has been resurrected and examined in a new light. He was a brilliant mathematician, the first Greek to demonstrate that tides were connected with the moon, and the first to discover an accurate method of determining latitude. His astronomical measurements were so precise that it now appears he was far removed from the imaginative mythologist some of his later accusers accused him of being. Many of his geographical descriptions and unparalleled local observations are so detailed and accurate that it seems certain he was who he said he was and did what he claimed he did.

- In Search of King Alcinous: Who were the Legendary Phaeacians?

- Floating Islands Seen at Sea: Myth and Reality

- The Realm of Poseidon: A Mythical Voyage Around the Aegean

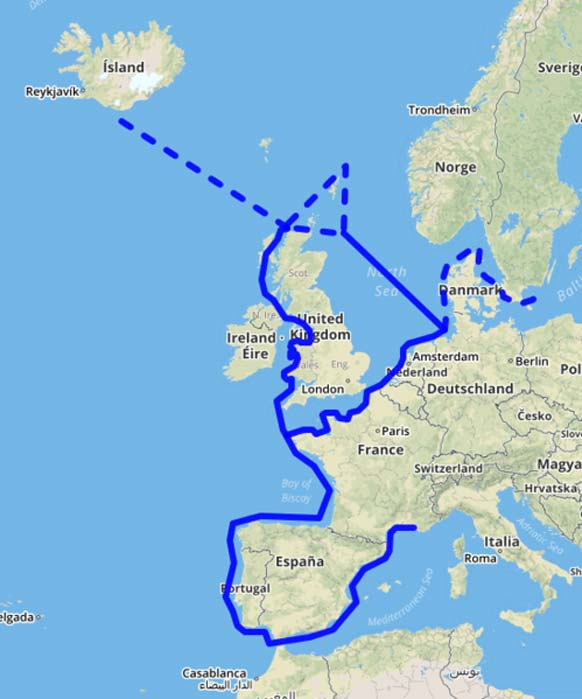

And those claims were remarkable. In short, he was the first to circumnavigate the British Isles and possibly the first inland navigator to view Iceland (Thule) and maybe even Greenland. His voyage around what he called the ‘three corners of Britain’ portrays an accurate description as far as miles traveled, latitudes covered, and geographical points sighted. From the ‘promontory of Kantion’ (Kent), to ‘Belerion’ (Cornwall) and then to ‘Orkas’ (the Orkney Islands), he vividly describes locations in terms only an authentic, observant visitor could have witnessed.

Map of Pytheas’ voyage (Fschwarzentruber / CC BY-SA 4.0)