Stairway to Heaven: Ancient Concepts About Heaven and the Afterlife

We recognize heaven as a place to which we will go after our deaths if we have led a good or virtuous life. It is a paradise accessible by earthly beings depending on their standards of faith or goodness. On the other hand, hell is home to evil, misery and many other unpleasant things - a place to which we will be sent if we have led unvirtuous lives. However, the concept of the afterlife in the ancient world is more varied and somewhat more complicated. Unlike travelling to hell, which seems to be a much quicker process, a soul’s journey to heaven consist of various tests and layers before it could reach its final resting place.

Prometheus Forms Man and Animates Him with Fire from Heaven by Hendrik Goltzius (1589) (Public Domain)

Indian Svarga and Greek Elysian Fields

Indian religions describe svarga (‘heaven) as a transitory place for righteous souls who have performed good deeds in their lives but are not yet ready to attain enlightenment. Therefore, a soul would pass through svarga before it is subjected to rebirth in different living forms according to the good or bad karma it has managed to gather in its life. This is somewhat similar to Greek and Roman mythology where the dead would usually either travel to the Underworld where they would stay or to the Fortunate Isles (or Isles of the Blessed), an earthly paradise for those who were judged as pure enough in their three lifetimes to gain entrance to the Elysian Fields, the final resting place of the souls of the heroic and the virtuous.

Sumerian Irkalla

For the ancient Mesopotamians, heaven is divided into three domes. The lowest dome of heaven was the home of the stars and the middle dome was the home of the Igigi - the younger gods. The highest and outermost dome of heaven was personified as An, the god of the sky. However, no ordinary mortal would ever have access to any of these domes no matter how virtuous they were in their lives as the heavens were the home of the gods alone. Unlike the more modern belief of the importance of a person’s action in determining whether they will go to heaven or hell, the ancient Mesopotamian belief was that all souls went to the same afterlife. Therefore, a deceased person’s soul went to Irkalla, the underworld below the surface of the earth.

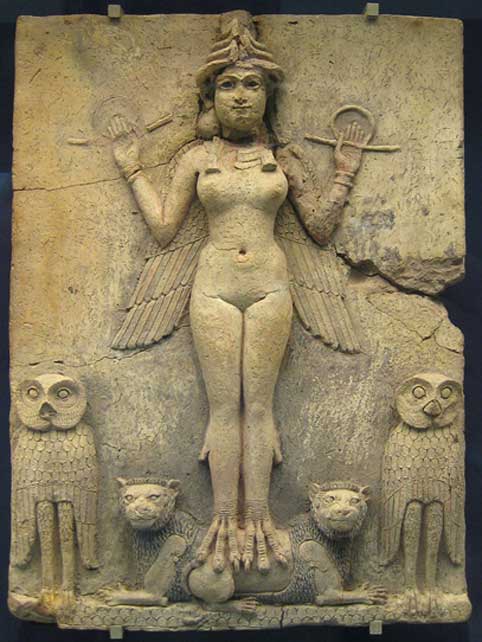

In Sumerian mythology, Ereshkigal, sometimes called Irkalla was the goddess of Kur, the land of the dead or underworld in Sumerian mythology. (CC0)

Literary accounts of the underworld are generally dismal. The underworld is described as a dark ‘land of no return’ and the ‘house which none leaves who enters’. However, Ur-Namma A (‘the Death of Urnamma’) describes the spirits of the dead rejoicing and feasting upon Urnamma’s arrival in the underworld. Grave iconography, specifically symbolism related to the goddess Ishtar who descended and returned from the underworld, indicates a belief in a more desirable afterlife existence than the one described in many literary texts. The Mesopotamian underworld is therefore best understood as neither a place of great misery nor great joy, but as a somewhat dulled version of life on earth.

Aztec Omeyocan

Much like the ancient Mesopotamians, the Aztecs believed that the heavens were divided into levels - in this case 13 levels. The most important of these 13 levels were the last two, which included Omeyocan, the dwelling place of the founder of the universe. However, for the Aztecs, it was how a person died that determined his lot in the afterlife. Warriors who died in battle or by sacrifice would go to a paradise in the east and joined the sun’s rising in the morning or join the war god Huitzilopochtli in battle. Women who died in childbirth went to a paradise in the west and joined the sun’s descent in the evening as they were considered just as courageous and honorable as warriors. People who died from particularly violent deaths or death by nature such as lightning or drowning went to Tlalocan, a paradise presided over by the rain god Tlaloc. In contrast, those who died of common illnesses, old age, or an otherwise unremarkable death went to Mictlan, the underworld, where they had to traverse through a harsh terrain with many trials in order to descend to its final level. This highlights the Aztecs’ tradition of placing greater esteem for people who died from premature but honorable deaths than for people who lived uneventful lives into old age.

- Once Upon A Time: Concepts of Afterlife and Altered Consciousness Concealed in Faerie Folklore

- Journey to Hell, Featuring Torture and Never-ending Bureaucracy: Understanding the Underworld in Chinese Mythology

- Descent to the Underworld: The Little-Known Practices and Symbols in Ancient Mythology of the Great Below

Welsch Annwn

In some cultures, although a particular realm presented the same characteristics as heaven, people did not necessarily have to die to visit it. In fact, although their journeys involved leaving their world to another world, the person was still very much alive. Therefore, for this purpose, the term ‘otherworld’ is more appropriate. Welsh mythology called the otherworld Annwn. The Welsh tale of Branwen, daughter of Llyr, ends with the survivors of the great battle feasting in the Annwn, forgetting all their suffering and sorrow, as well as becoming unaware of the passage of time.