The Mind-Body Problem: Mankind’s Elusive Enigma

What is the universe? Where did it come from? Does it still exist when we die? Do we create the universe, or does it create us? These questions all pertain to what has become known as the mind-body problem - a term describing ancient philosophical meanderings to any relationship which might exist between consciousness and the mechanics of the physical body. In order to understand the relationship between man’s thoughts and actions, and how mankind’s forebears approached these timeworn questions, one may consult the early 20th-century esotericists and ceremonial magicians and their attempts to answer the questions.

Relationship Between Mind and Body

A 2001-paper published by the Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara, titled Evolutionary Psychology and the brain revealed that although the mind-body problem has ancient origins, the lines of questioning it brings forth have been influential in the modern sciences of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology and in neurosciences. Any scientific theory of consciousness has to explain how the brain’s varying states can electrochemically generate subjective consciousness, and this has become known as the ‘hard problem' of consciousness. Neurobiologists, neuropsychologists, neuropsychiatrists and neurophilosophers all study neuroscience and philosophy of mind for signs that consciousness is generated by our complex biological systems, but these empirical approaches implies a presupposition that mind and body ‘do’ affect each other; but the mind–body problem holds that the mind and the body might be fundamentally different in nature.

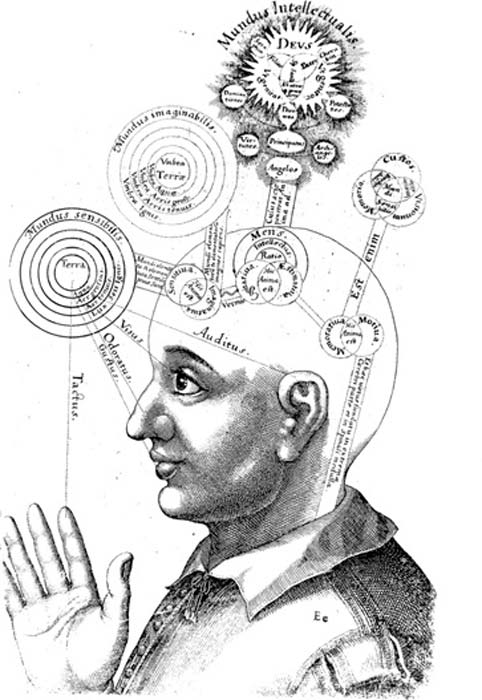

Representation of consciousness by the 17th century by Robert Fludd, an English Paracelsian physician. (Public Domain)

Historically, the reason why so many schools of thought concerning the mind-body problem existed, was essentially because of the lack of an empirically measurable point in space-time where the mind and body can be said to unite. This is to say, there is nowhere measurable or tangible that an observer can say: “right there at coordinates x, y, z, at such and such a time, the body creates conscious experience, or, conscious experience causes the body to act”.

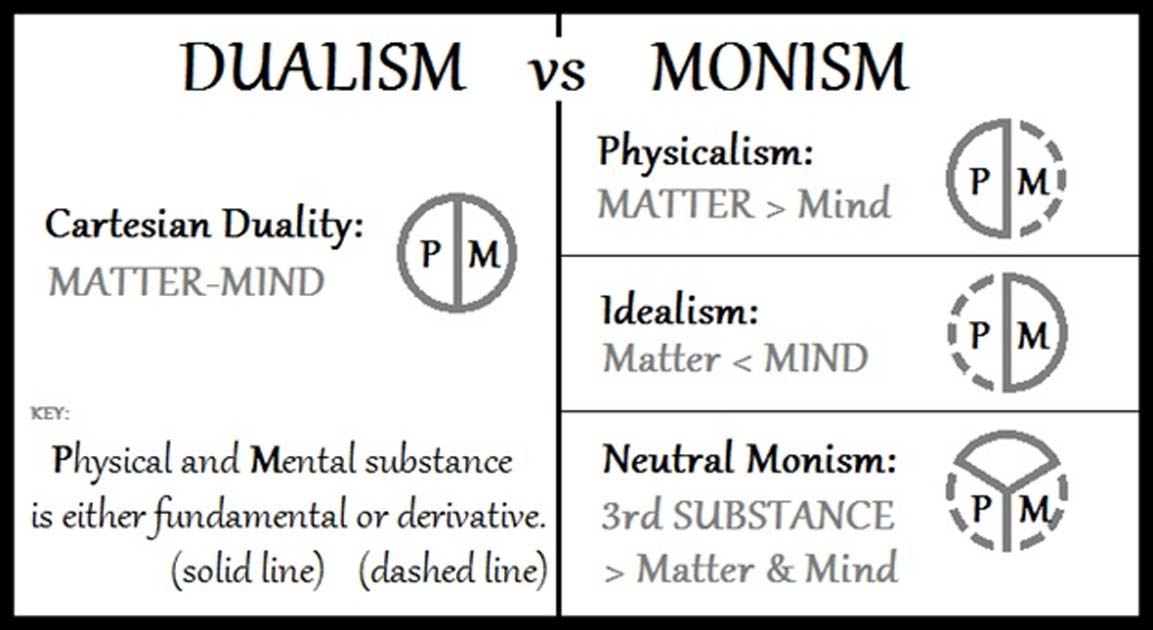

Some of history’s sharpest minds have attempted to solve this problem and three general approaches have been proposed; monist, dualist and psychophysical parallelism. According to scholar Jaegwon Kim in his book Supervenience and Mind, 1993) monism proposes that all essence, substance and unified reality is one thing, inseparable, and there are three subcategories; ‘physicalism’ is where the mind consists of matter organized in a particular way; ‘idealism’ where only mind exists and matter is an illusion, and ‘neutral monism’ where both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence. Contrary to monism, dualism maintains a rigid distinction between the realms of mind and matter holding that mental phenomena are non-physical or that the mind and body are distinct and separable. Paul Churchill’s excursion into reality, Matter and Consciousness, (1984) proposes ‘substance dualism,’ – meaning the mind is not governed by the laws of physics and is formed of a distinct type of substance and ‘property dualism,’ - meaning conscious and mental experience is generated ‘within’ the fundamental laws of physics. Psychophysical parallelism is a halfway house that lies between interaction (dualism) and one-sided action (monism).

The essential differences between monism and dualism. (Public Domain)

Buddhism on Consciousness

While the modern study of consciousness is greatly undertaken in laboratory environments with extensive social experiments often involving tens of thousands of participants from all over the world, already in the fifth century BC (480 - 400 BC) Buddha taught that the world consisted of mind and matter working together, interdependently, and he described the mind and the body as: “depending on each other in a way that two sheaves of reeds were to stand leaning against one another.”

In Carol Anderson’s book Pain and Its Ending: The Four Noble Truths in the Theravada Buddhist Canon (1999) the author described the Vijñāna which translates as life force or consciousness. The Anattā doctrine of the Buddha states the mind is said to manifest from moment to moment, now, now and now, like a flowing stream. Reality is defined with a conceptual tool known as ‘the five aggregates’ which are; material form, feelings, perception, volition and sensory consciousness, which are believed to occur and pass continuously under the influence of five causal laws: biological laws, psychological laws, physical laws, volitional laws, and universal laws. Buddhist mindfulness is the constant alignment of these ever changing, flowing, streams of conscious thought, and when Nirvāna is achieved these phenomenal experiences ceased to exist.