Ancient Symbolism of the Owl: Omen of the Good, the Bad and the Deadly

About 48 million years ago, an owl swooped down to catch its prey in broad daylight - we know this because in 2018 Dickinson Museum Researchers found the exquisitely preserved remains of the owl. Its skull shares a telltale characteristic with modern-day hawks which also hunt by day. As they have evidently existed since the ancient times, the owl has been regarded with fascination, awe and fear throughout history. They feature prominently in the myths and legends of a variety of cultures.

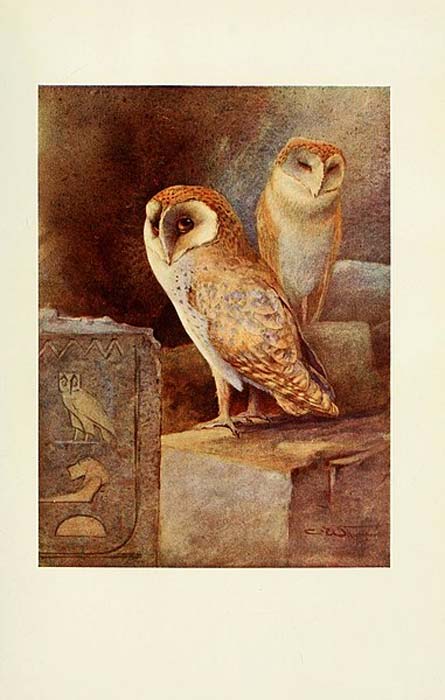

Egyptian birds for the most part seen in the Nile Valley, Screech Owl (1909) (Public Domain)

Ill Omens

An owl's appearance at night, when people are helpless and blind, linked them with the unknown. Pliny (23-79 AD) described the owl as: “the very monster of the night” and argued that: “when it appears, it foretells nothing but evil.” However, despite his apparent distaste for owls, Pliny also believed that the viscera of owls held curative properties that could restore health and relieve pain. For example, a healthy mixture of owl brain and oil dropped directly into the ear canal was a handy cure for an earache.

Hooting of the owls was regarded an ill omen. In Ancient Egypt, if a lowly official received the glyph of an owl from the pharaoh, it was understood that the recipient had to take his own life. In the Teotihuacan culture, the owl was also seen as an evil omen as well as one of the many sacred animals of the rain god Tlaloc. By the Middle Ages in Europe, the owl had become the associate of witches and the inhabitant of dark and profane places.

The Owl of Athena. Acropolis museum, (fifth-century BC.) (CC0)

Mesopotamian and Levantine Owls

The Sumerians called the owl the ukuku. An example is from the Cursing of Agade, an ancient Mesopotamian story written around 2100 BC: “May the ukuku, the bird of depression, make its nest in your gateways, established for the Land,” and: “The bird of destroyed cities… The sleep-bird, bird of heart’s sorrow.” In ancient Syria, the owl is found recorded in the eighth-century treaty in the Aramaic inscription from Sefire, in which the owl serves as an emblem of desolation.

Owls appeared in graves from the earliest layers of the Carthaginian settlement, contemporary with the Tyre al-Bass cremation burials. Two claws from a species of owl native to Lebanon were identified. A close examination of their remains revealed that, before being placed in the fire, these owls had been cooked or boiled. The excavator surmises that the remains of a meal or offering had been placed on the funeral pyre together with the corpse of the deceased and subsequently mixed with the human remains in the burial urn. The Phoenicians/Sidonians Hebrews sacrificed owls to be included in their burials back to the seventh century BC.

- The Supernatural Traditions of the Alaskan Shaman

- From the Ancient Greek Pleiades to the Hindu Matrikas: Mother Goddesses, Music and the Sacred Number 7

- Millions of silver coins may have been stored in Parthenon attic

Biblical Owls

In biblical law, owls are included in the list of birds that were not to be eaten. An oracle concerning Edom, Isaiah 34:11 declares that: “The desert owl and screech owl will possess it; the great owl and the raven will nest there. God will stretch out over Edom the measuring line of chaos and the plumb line of desolation.” The eagle owl roosts on the capitals of a desolated Nineveh in the prophetic vision of Zephaniah 2:14 which says: “Flocks and herds will lie down there, creatures of every kind. The desert owl and the screech owl will roost on her columns. Their hooting will echo through the windows, rubble will fill the doorways, the beams of cedar will be exposed.” Later the owl deity known as Ashtarte becomes the demon goddess that is known as Lilith, who was created in the first Genesis account.