The Impact of Agricultural Developments on Social Hierarchies

Throughout the history of mankind, major innovations drove us forward. But as they did so, they also changed us profoundly. No great shift in the way humans lived came about peacefully or smoothly. Instead, it caused upheaval, cultural changes, migrations, and the inevitable shaping of the future. Agriculture is, without a doubt, one of the foremost of these innovations that shaped the way humans lived for millennia. It came about gradually and influenced the traditional societies of prehistory in a very profound way. And, without a doubt, it set the course for the future as we know it today. But how did agriculture impact social hierarchies of the time? Or better yet, did agriculture create them?

- Agriculture First Versus Göbekli Tepe: Prehistory Revisited

- Göbekli Tepe, Birth of Civilization and Religion

The Mobility and Egalitarianism of Pre-Agricultural Societies

Long before agriculture became a “thing” in the distant past, human societies were predominantly small nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers. Their lifestyle was largely unaltered for centuries - they crafted stone tools and migrated together with the animals they hunted. It was a simple, but efficient life. These groups were also characterized by a relatively egalitarian social structure, without castes and with minimal - if any - hierarchy. There was a strong emphasis on communal sharing, and everyone “pulling their load”. Most of the resources were gathered collectively through hunting, foraging, and fishing, and were distributed within the entire group to ensure the survival of its members. This teamwork was the key to survival and made hierarchies simply redundant. Another key factor in this egalitarian lifestyle was the mobility of the hunter-gatherers. This mobility meant that no individual or family could accumulate significant wealth (was there even a concept of wealth at that time?) or power due to the constant need to move in search of food.

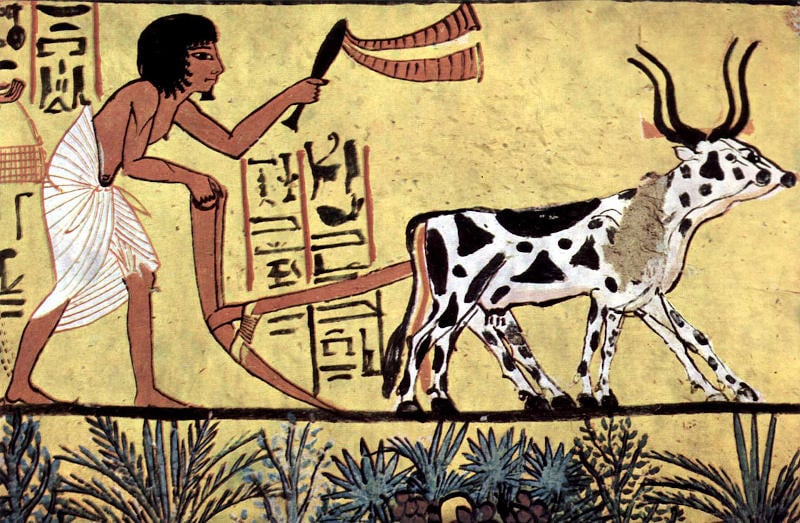

Painting of ancient Egyptian farmer tilling the soil. (Public Domain)

There existed leadership in these societies, however, and was generally informal and based on merit. This included hunting skills, charisma, fertility, survival abilities, and the knowledge of the land. Of course, there were no fixed institutions of power, and all major decisions were made collectively or by general agreement. This natural lifestyle and the fluidity within a social organization meant that all group members participated equally in everything. And there was thus no need for the creation of hierarchies or centralized authority. It is because of this that most scholars and historians agree that this was the “golden age of mankind” - i.e. the natural lifestyle of humans. All subsequent innovations, however useful, were only detrimental to the nature of humans. And one of the major changes that altered this dynamic was agriculture.

The Surplus and Sedentarism Introduced by the Agricultural Revolution

The Agricultural Revolution, also known as the Neolithic Revolution, did not happen overnight. It came about roughly 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, and evolved over millennia, influenced by a combination of technological, environmental, and social factors. The major environmental factor that contributed to its emergence was the end of the last Ice Age, some 12,000 years before present. As the world experienced a significant warming trend, the glaciers retreated, and the climate became more stable. This meant that large areas of land were now more hospitable to plants and animals, especially in areas such as the Fertile Crescent in the Near East, one of the cradles of civilization.

And as new and emerging societies mastered the working of the soil and grew food from it, major changes began occurring. The gradual transition to agriculture allowed these societies to produce surplus food, and this was the fundamental change in the relationship between humans and resources. For thousands of years the people relied on the unpredictable and often limited resources in their natural environment. But the agricultural societies could depend on the seasons, cultivate crops, and domesticate animals, which ensured stable and predictable supplies of food. And as you create a surplus of food your society is able to settle in one place for an extended period of time, making the nomadic lifestyle no longer needed. And with that came permanent settlements, which evolved into the first cities in the world.

Without a single doubt, it was this ability to create and store surplus food that irrevocably changed the nature of prehistoric societies. Nothing was the same anymore. Before agriculture, the hunter-gatherer societies distributed goods (there was no wealth to be had) equally amongst themselves, as they all depended on one another. In stark contrast, the storing of food in agricultural societies created the possibility of individuals or small groups to control larger shares of resources. And it was this control over surplus resources that became the foundation of social inequality and gave need for hierarchies and distinct social classes.

- Food Security: Rethinking The Agricultural Revolution

- The Ancient Celtic Thresholds Of Liminal Time And Space

A Change in the Nature of Humans

Another major change that came about profoundly affected the rise of social hierarchies. It was sedentarism, the practice of living in one place for a long period of time. As this gave rise to permanent settlements and first “cities”, it also created the need for the construction of durable and efficient homes, granaries, and other functional structures. In turn, this further solidified the wealth and power of individuals that controlled resources and land. And the accumulation of material wealth became increasingly associated with social status - ownership of the land and control over agricultural production became central to the emerging social order. But to make matters worse, some individuals were prepared to stop at nothing to become those in control. This gave rise to violence between societies, to plunder and raids, and the eventual emergence of organized warfare.

With the arrival of agriculture, societies became more stratified and distinct social classes emerged. Besides this, the populations were able to grow due to the abundance of food, and that meant that not everyone had to be directly involved in food production. This was another major contrast to life before agriculture. Many individuals were now able to adopt specialized roles, becoming priests, artisans, or warriors. This led to the division of labor and the rise of new professions. This specialization allowed for accumulation of wealth and influence by those who were not in agrarian roles, further entrenching social hierarchies.