Akhenaten And Nefertiti: Egypt’s Golden Couple

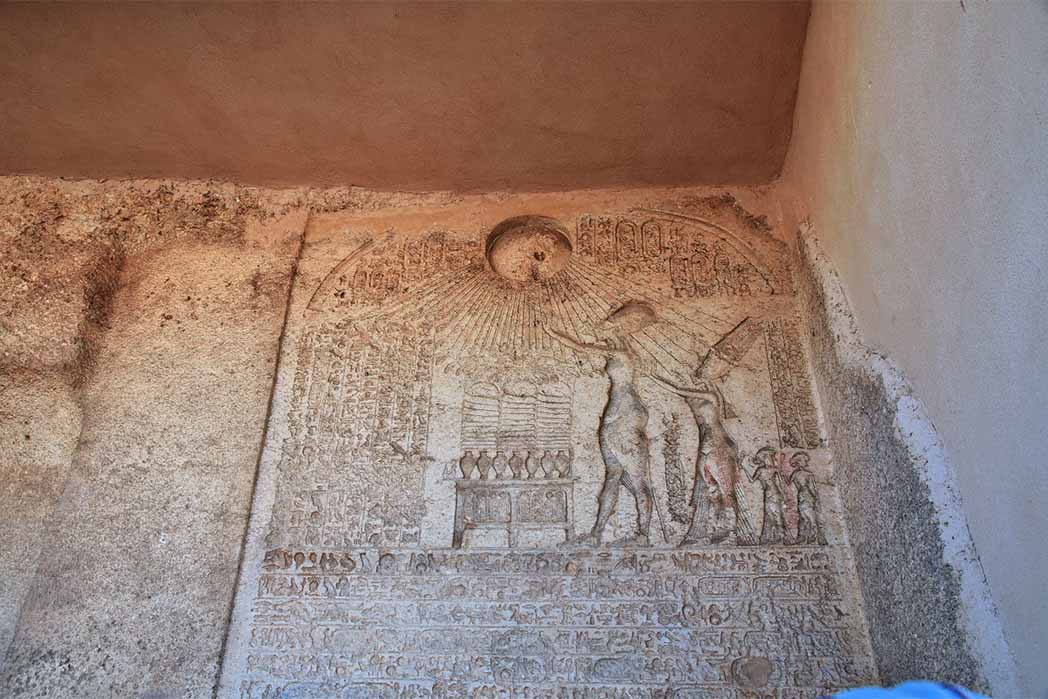

The drivers arrange the chariots of the royal entourage—two to one side, two to the other side, of the royal chariot, which is distinguished by the great ostrich plumes of its span of stallions. While the horses neigh, the accompanying bodyguard, winded by their jog alongside the rattling royal conveyances, turn and bow towards the royal family and the front of the temple. Followed by two men holding tall semi-circular ostrich-feather fans, and six women holding thin, elegant single-feathered fans, the king and queen head toward the temple, the princesses in their wake. Greeted by the temple staff, and passing by offering tables, heaped with the food that Aten and then his human worshippers will consume, the group make their way to the sanctuary.

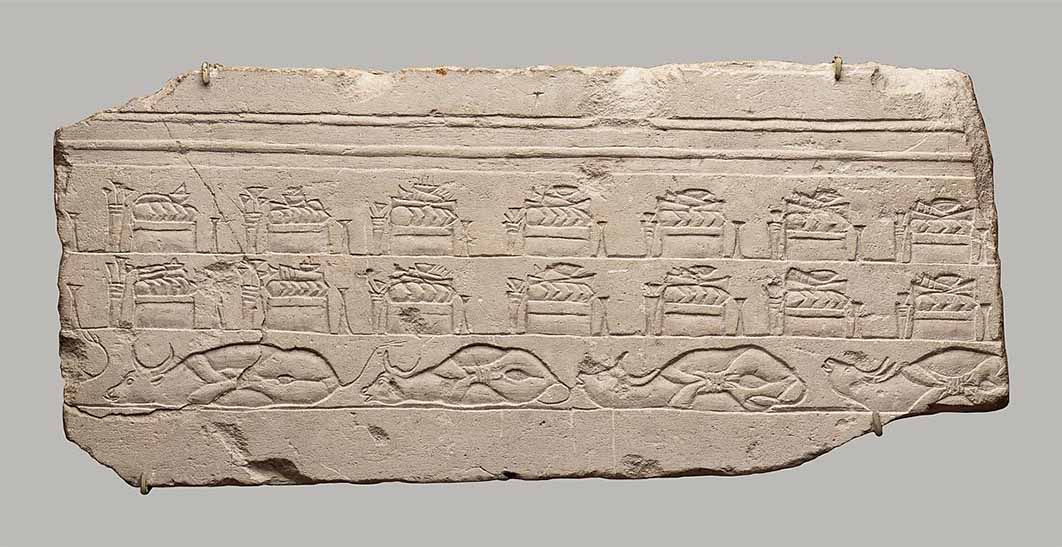

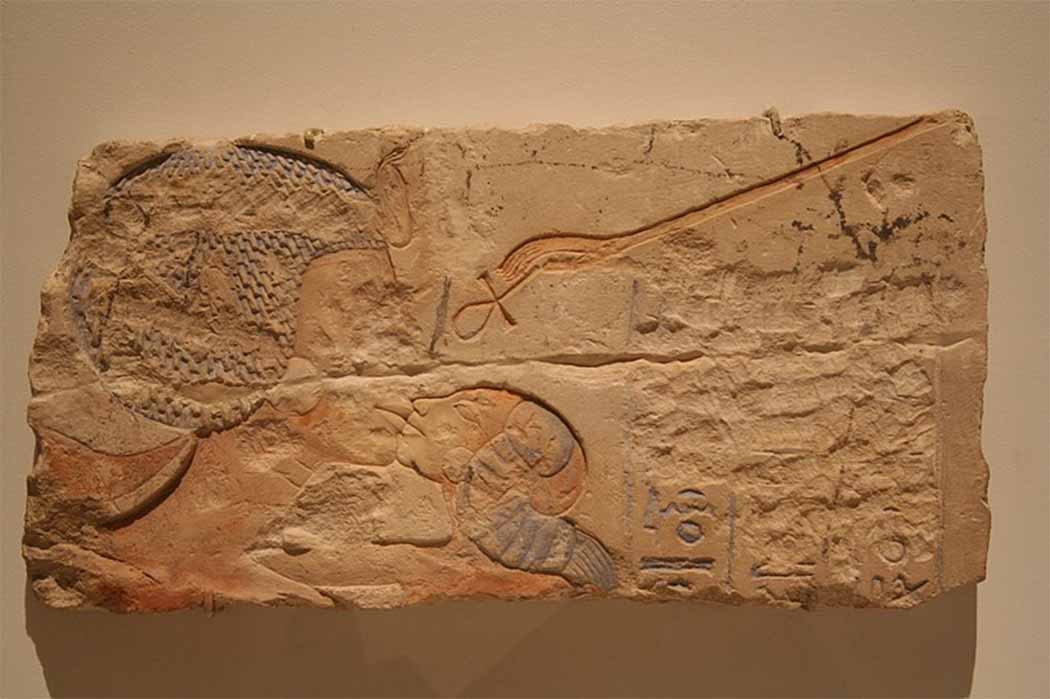

Talatat with offerings in the Temple (ca. 1353–1336 BC) New Kingdom, Amarna Period. Metropolitan Museum (Public Domain)

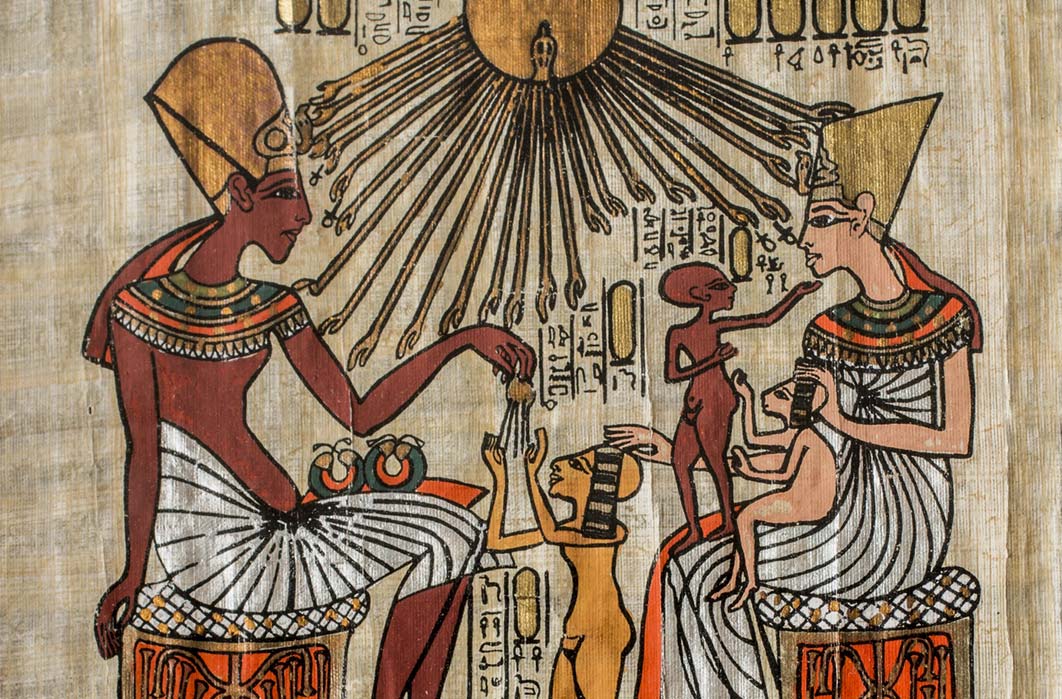

Today, Akhenaten and Nefertiti will elevate to the Aten jeweled examples of the god’s own name. Standing before an altar piled high with breads and all manner of cuts of beef, ringed around by jars of wine, and topped with burning dishes of incense, the king raises an object with two miniature versions of himself adoring the twin cartouches of Aten. Each figure wears the side-lock of youth—the daughters had more than once that morning laughed at the depiction of their father as a child—and bears multiple ostrich feathers atop his head, appropriate for the god Shu, son of the creator god. Behind him, Nefertiti raises a slightly smaller version of the same. The object she offers has but one figure adoring the Aten cartouches, a squatting version of the queen, in the pose of a child, her Tefnut to her husband’s Shu. Behind them, stand their own daughters, Meritaten, Meketaten, and Ankhesenpaaten, in diminishing size and age.

Akhenaten and his family paying tribute to Aten ( Sergey /Adobe Stock)

Of course, Meketaten insists on taking up Ankhesenpaaten’s small sistrum, as usual teasing her young sister, with the inevitable results, today bordering on a true tantrum. Nefertiti has to sort out the sistra, allotting each to its proper owner. Finally, each of the girls has her own instrument and shakes it, the rattling sound accompanying and giving rhythm to the proceedings. As small as the daughters were, and as much trouble as the young Ankhesenpaaten sometimes had in keeping time with her older sisters, their tinkling accompaniment is a key part of the ritual in the Estate of Aten. As a family, they ensure that the solar orb in heaven remains in a constant state of jubilee.

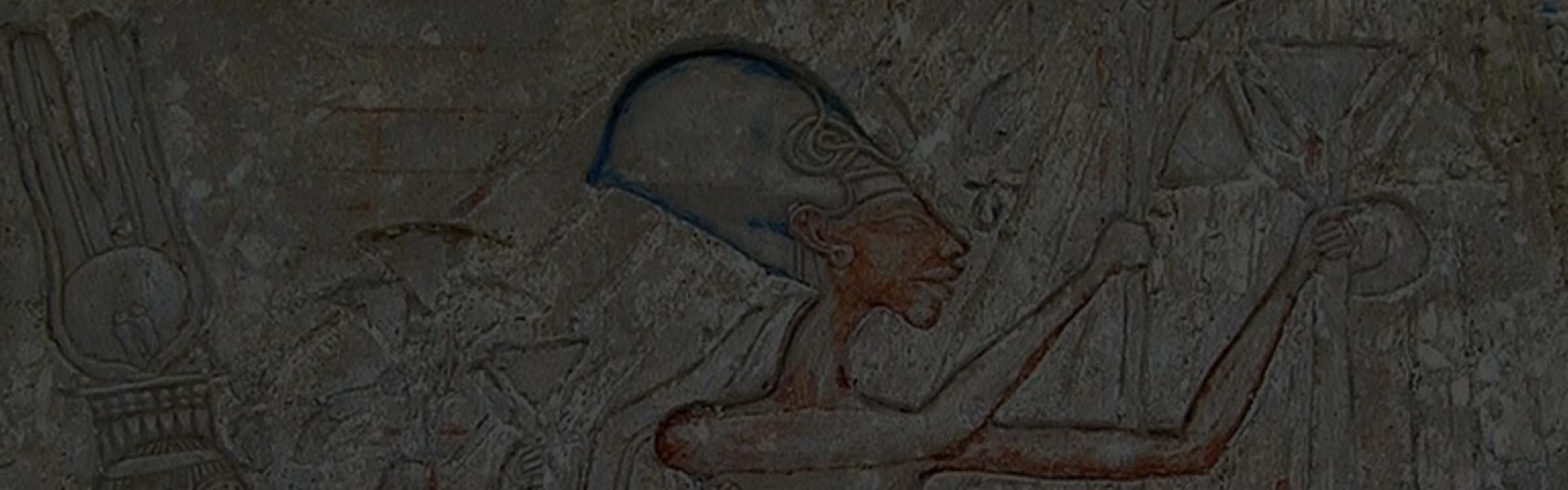

Limestone relief of Nefertiti kissing one of her daughters, Brooklyn Museum (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Performing Princesses

Akhenaten was unusual in showing his wife and daughters his constant companions, but kings, including Amunhotep III, did include young men and women labeled “royal children” and “royal daughters” during jubilee ceremonies continuing a much older tradition. The great classic story of Middle Kingdom literature, The Story of Sinuhe, describes how the daughters and the chief queen of Senwosret I—the women of the immediate royal family—entertain the king. This episode illuminates how an ancient Egyptians might have ‘read’ the images of Nefertiti and her daughters continuously surrounding Akhenaten, especially those representations of the princesses wielding sistra. This story would have been familiar to the king, queen, and literate members of the royal court.