Akhenaten: Imperishable Art of an Iconoclast: Creativity Blossoms in the Desert—Part I

Never before had a pharaoh ushered daring, almost bizarre and inconceivable transformations in religion and statecraft as Akhenaten did. Not only did he oust the pantheon of traditional gods and shift the royal capital from Thebes to Akhetaten down river in middle Egypt; in doing so, he altered the course of ancient Egyptian history forever. But Akhenaten’s introduction of a new artistic convention continues to captivate viewers down to this day.

Even though little remains in Akhetaten, the once-bustling, defiant capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten; its allure remains unchanged. A restored column in front of the Sanctuary of the Small Aten Temple in Akhetaten. Tell el-Amarna.

Pharaoh Amenhotep IV—(later Akhenaten, reign 1353–1336 BC) the heir of Nebmaatre Amenhotep III of the Eighteenth Dynasty (New Kingdom)—was a determined man who brooked no indifference. In one controversial stroke, the ruler overturned centuries of religious beliefs dear to his people. Every walk of life came under the ambit of Neferkheperure-waenre Akhenaten’s sway. The singular transition that affected the lives of all his subjects was the introduction of Atenism as the state religion, replacing the much-celebrated Amun cult. That was not all: it was decreed that the solar disc would henceforth be the sole and supreme god, and the pharaoh, his earthly intermediary, priest and prophet.

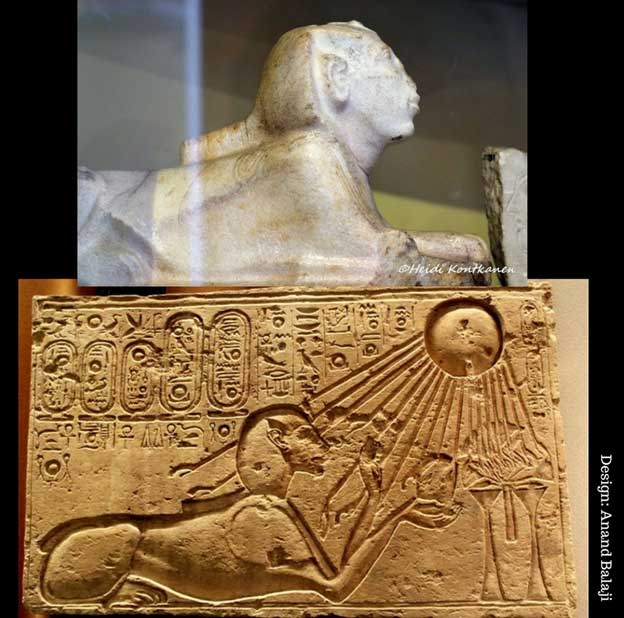

Although Akhenaten’s religious reforms purged Egyptian art of many deities, the King remained fond of the sphinx, and often had himself depicted as that fantastic creature. In the Eighteenth Dynasty, the monument was reinterpreted as the sun god Horemakhet, or ‘Horus in the Horizon’. (Top: Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Below: Hans Ollermann/CC BY 2.0. Museum August Kestner, Hanover, Germany.)

Unlike the legion of Egyptian gods and goddesses, the Aten was not depicted in anthropomorphic form, but was instead represented as a radiant solar disc with a uraeus and rays emanating from it, ending in hands, either left open or holding ankh symbols. Also, the deity’s name was ensconced within a royal cartouche.

A limestone column fragment bears an early name of the Aten within a cartouche. Petrie Museum, London. (Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Aten was considered both masculine and feminine simultaneously; and more importantly, the Creator of all things. So, while the pharaoh and his queen worshipped the Aten, their subjects worshipped them. This abstract god must have traumatized the ordinary Egyptians, because it meant that the familiar deities who played a role in ensuring their well-being on earth and assured safe passage into the afterlife were obliterated, especially Osiris.