Female Contenders For Alexander’s Crown: Cynane, Adea, Olympias

Behind every successful man stands an ambitious woman, the saying goes, more-so if she is a blood-relative of Alxander the Great, and a warrior. Claiming descent from Herakles, the son of Zeus, through his great-great-grandson Temenus, King of Argos, the Argead Dynasty were the founders and rulers of Macedon from about 700 to 310 BC. The kingship of Argead was personal in its style. The king wielded the real power and authority and, except of course for the king himself, all positions were held ad hoc and at the king’s discretion. Therefore, influence in the Argead Dynasty of Macedonia was entirely dependent on one’s access to the king's person. If a king wished to delegate authority, he would do so for as long as the person so honoured was able to maintain the king's trust. Thus, the realm was, in essence, an extension of the royal household where the king assumed the rights and responsibilities as the head of the household and as its patriarch as it was respected throughout the Greek world at the time. As such, the king’s power was not only constitutional, but also founded on religious and moral authority.

Golden Larnax with the Sun of Vergina on the lid that contains the remains from the burial of King Philip II of Macedonia and the royal golden wreath. Verginia Museum (DocWoKav/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Argeads never had a well-defined succession principle, and it appears that the only requirement for a would-be monarch to be considered for the throne was that he had to be a male member of the Argead family. However, despite the undeniable fact that sons frequently succeeded fathers, because Macedonia was almost never free of significant foreign threat, competence and ruthlessness were more important for kingship – and women were also often just as capable of being as competent and ruthless as their male counterparts, if not more so. Therefore, although sons had strong claims on the loyalty of the people when their royal fathers died, the throne was almost always rapidly seized by the strongest adult Argead male available at the time, who may or may not have been backed by an Argead female holding almost just as much power behind the scenes. Such were the likes of Alexander’s half-sister, Cynane, her daughter Adea, and his mother Olympias.

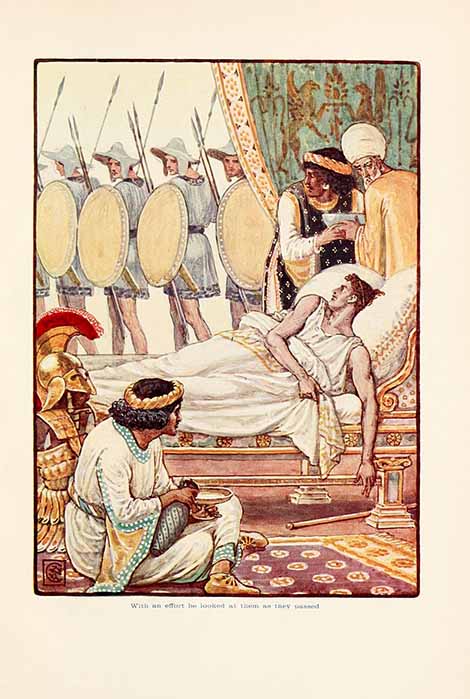

Alexander on his deathbed looking at his soldiers in ‘The story of Greece’ by Walter Crane (Public Domain)

Alexander’s Succession Dispute

This insight into the dynasty became prominent at the end of Alexander the Great’s reign, and no doubt every single female relative of Alexander’s was aware of the potential power she would hold if she had the king’s ear. As Alexander was himself conscious of removing potential royal rivals at the beginning of his reign, and because he was never particularly concerned with fathering an heir, the only adult Argead male living at the time of Alexander's death, was his half-brother Arrhidaeus (c. 359 – 317 BC) who was widely considered to be too mentally deficient to rule a kingdom and, although Alexander's Bactrian wife Roxane was pregnant at the time of his death, no one knew whether the pregnancy would result in a son. The conundrum of not having a direct, competent male heir to the throne was so unusual that no one knew what to do with the Argead throne, until Alexander’s son, who was at that stage still unborn (and the fact that the baby would be a male was still uncertain), could assume authority in his own right. This created an unprecedented situation at a particularly dangerous time for the Macedonians before the vast Persian Empire was fully pacified.

Roxana with Alexander IV Aegus the son of Alexander the Great by Alessandro Varotari (Public Domain)

Although Roxane would eventually give birth to a son who was later known as Alexander IV, long before his birth a near-civil war within the Macedonian army presented an unpopular solution to the question of the succession to the throne. Under the leadership of Perdiccas, one of the highest-ranking officers in Babylon where Alexander the Great died, it was agreed that the inept Arrhidaeus would become king, albeit mostly only to perform important religious rituals associated with the position. However, if Roxane had a son, that child would also be recognised as king. Therefore, when Alexander IV was born, an unprecedented joint kingship was then established. Perdiccas used his rather lucky position of being in possession of Alexander the Great's body and signet ring, to gain widespread recognition of his role as the kings' regent and protector. However, to secure this recognition, Perdiccas also had to oversee a general distribution of powerful appointments to his military peers. This distribution would later lead to the dismemberment of Alexander the Great's Empire.