Ancient Australian Song-lines

Indigenous Australian cultures held animistic beliefs and their everyday reality was a living, pulsing matrix of mythological cycles, outdoor rituals and ceremonies. Extending across the ancient Australian landscape are hundreds of long-distance alignments called song-lines which are dotted with thousands of sacred sites, shrines and natural outdoor temples. Ashley Cowie investigates the underlying cosmology of these landscape alignments and answers the question as to how ancient indigenous people memorized so many places over such great distances.

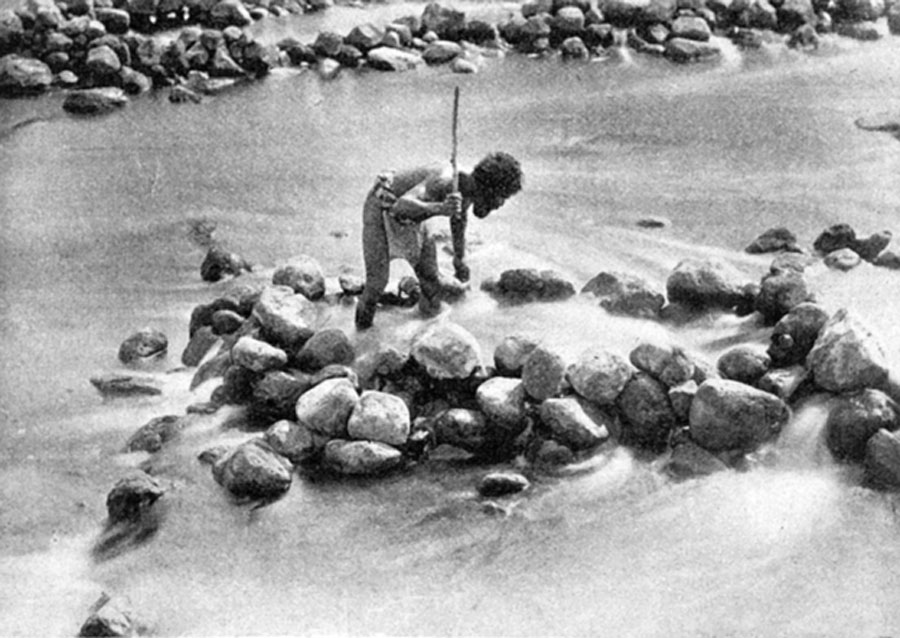

Walking the length of a long song-line was thought of as taking an extended ‘Walkabout’, which is when young men spent time ‘walking about’ in the wilderness during their a coming of age ceremony, surviving on the land and providing for themselves. (Public Domain)

In the ancient Australian animistic world, animals were given complex personalities and characteristics and tribal elders, who were described in detail by anthropologist A.P. Elkin’s classic text Aboriginal Men of High Degree, believed they could communicate with animal spirits and acted as community conduits between this world and many others. It was not only animals that were perceived as holding spirit, but also mountains, hills, cliffs, rocks, trees, deserts and rivers.

A Ngarrindjeri elder in a smoking ceremony, an important part of the repatriation of Old People remains. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Dreamtime: Long Distance Dreaming Tracks

‘The Dreaming’, or ‘The Dreamtime’, is a term used to refer collectively to Aboriginal religious beliefs which attempt to explain the phenomena of past, present and future realities, including the origins of humans and animals. The various cultures identified with different creator gods and their spirits were perceived as inhabiting the land. Song-lines, sometimes called ‘Dreaming Tracks’, are straight, long distance paths leading across landscapes, and were sometimes drawn in the sky between stars and constellations which delineate the routes followed by localized creator-beings during ‘the Dreaming.’

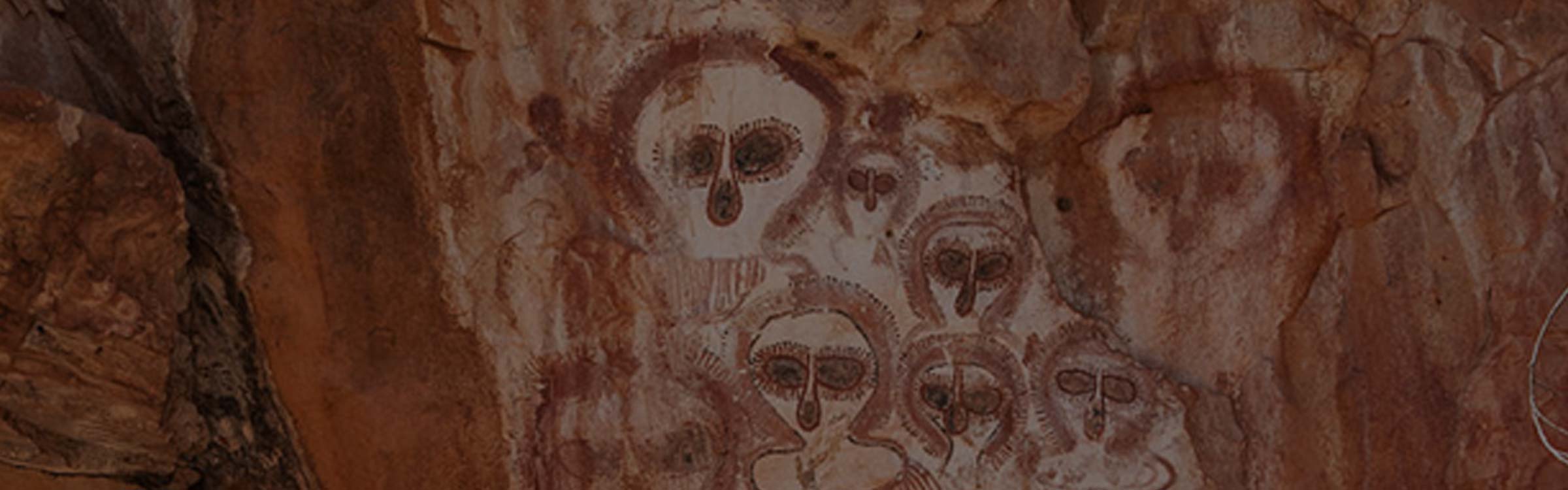

Some song-lines are only a few kilometers long whilst others extend across hundreds of kilometers through the territories of many different indigenous peoples, who speak a range of different languages, and have different cultural traditions, yet they have songs describing the same lines. Many researchers incorrectly compare the song-lines of Australia to the ley-lines of Europe, the apparent alignments of landmarks, religious sites and man-made structures which some researchers speculate may have deep spiritual significance. Opinions differ, as others point out the lack of tangible evidence to support the ley-line theory on the subjective alignments discovered on maps and on the field. While in Australia, song-lines and correlating natural features’ alignment are recorded in traditional songs, folk-stories, dances and in rock paintings and carvings.

A 19th-century engraving of an Indigenous Australian encampment by Skinner Prout (1876). A humpy (or gunyah) is a small temporary shelter traditionally used by Australian Aboriginals while traveling on long-lines. (Public Domain)