Grand Alliances: The Anglo-French War 1294 – 1303

In 1294, after almost 30 years of peace, England and France went to war. This sowed the seeds of the conflict known as the Hundred Years War, the era of the longbow and the famous Battles of Crécy and Agincourt. Despite a string of English victories, it ended in 1453 with the French conquest of Aquitaine and the fall of England's last territories on the continent, save Calais.

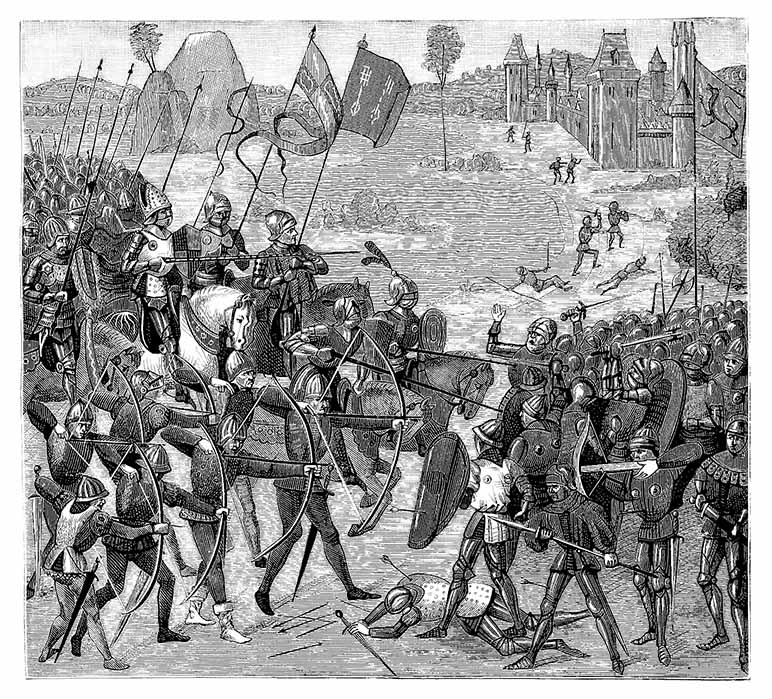

Anglo-French Conflict – (14th century) (Erica Guilane-Nachez/Adobe Stock)

Treaty of Paris 1259

The Anglo-French War was originally a duel over sovereignty between rival monarchs, rather than a war between nation-states. It was fought over possession of Gascony (also called Guyenne). Via the Treaty of Paris, in 1259, King Henry III of England had signed away the bulk of his ancestral lands in France, including Normandy and Anjou, to King Louis IX of France. These lands had once formed the so-called Angevin Empire, constructed by King Henry II in the previous century. Most of these vast territories were lost by King John, and his successor Henry III's efforts to recover them proved futile. In 1259, after decades of intermittent warfare, Henry III was forced to bow to reality. He was allowed to keep the land of Gascony, a smaller portion of the old duchy of Aquitaine in south-west France, centred on Bordeaux. However, Henry III and his successors would not hold Gascony in their own right, but as vassals of the King of France. This placed the kings of England in a compromised position. After 1259 they were just one of many grand seigneurs of France, owing the French King homage and fealty, liable to do military service on demand.

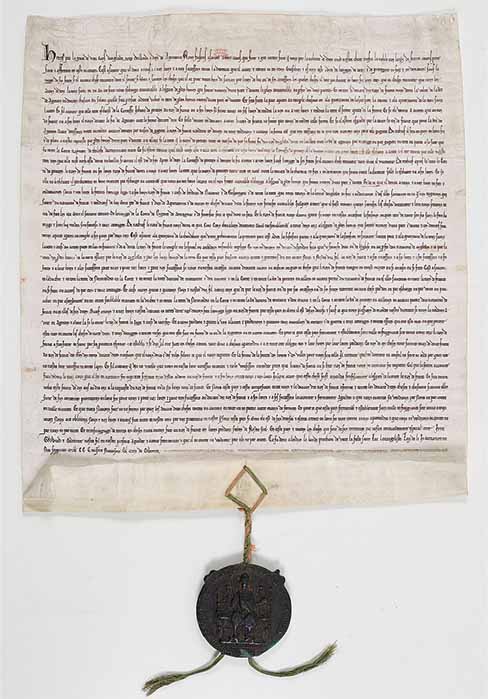

Ratification of the Treaty of Paris by King Henry III, 13 October 1259. Archives Nationales, France. (Public Domain)

Visions of a French Empire

Even so, the treaty secured peace between the two kingdoms for a generation. Relations between the royal houses of Plantagenet and Capet were generally good, and Henry's successor Edward I, called Longshanks, skilfully avoided conflict with his French overlords. Then, in 1285, a young and ambitious French king, Philip IV, succeeded to the throne. Known as Philippe le Bel (Philip the Fair), he and his advisers had grand visions of an empire, in which France expanded in all directions. To that end Philip and his brother, Charles of Valois, planned to conquer Gascony outright.

In 1294, after a series of botched negotiations at Paris, Edward I formally renounced his homage and declared war on Philip IV. The military operations that followed ended in deadlock. Philip's initial invasion of Gascony was a success, largely because the English had unwisely agreed to surrender key towns and fortresses. Determined to reverse this humiliation, Edward embarked on feverish military preparations. His expeditionary force was able to recover part of Gascony, including the port town of Bayonne, but he failed to take Bordeaux. A French counter-attack, led by Charles of Valois, ground to a halt in the blazing heat of a summer campaign, and the war drifted into stalemate.

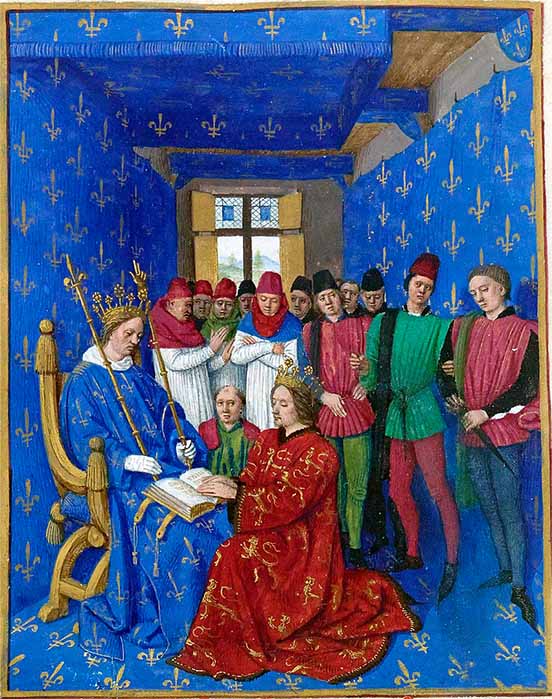

In May 1286, King Edward I paid homage before the new king, Philip IV of France, for the lands in Gascony, by Jean Fouquet (1455) (Public Domain)